In 1939 Richard Serra expressed the importance of site-specific work not becoming or being seen as a token, decoration or reinforcement of the institution it is situated in. He also explains that at the time because large scale, site- specific sculptures were hardly ever considered a ‘worthy investment’, as they would be difficult to re-sell, many artists became willing to accept corporate sponsorship and support as it created economic opportunism. However, he further expresses that these artists just become ‘puppet creators’ and their art just becomes a ‘public service’ and that this is wrong, that the “aspiration of art cannot be to serve”.

Richard Serra explains that his use of industrial tools and methods and making site specific works allowed him to work out of the ‘traditional’ studio. He was able to “extend their tool potential”, using the tools in a different way, making them what they’re not, giving them a new meaning, purpose and view. “To be able to enter into a steel mill, a shipyard, a thermal plant and extend both their work and my needs is a way of becoming an active producer…- not a manipulator or consumer” Serra explains he steers from tradition, doesn’t stick to the classical ‘rules’ and doesn’t copy other artists typical ways of practice. He doesn’t just take to make, he gives the tools and methods a new definition and purpose.

This diversion from tradition is relatable to Leo Steinberg’s theory of the introduction of ‘The Flatbed Picture Plane’,- how in the early 1950’s art no longer depended on a “head-to-toe correspondence with human posture” like the earlier ‘Old Masters’ had stuck to. This new display of art steered away from tradition, like Richard Serra.

Steinberg illustrates that “The flatbed picture plane makes its symbolic allusion to hard surfaces such as tabletops, studio floors, charts, bulletin boards—any receptor surface (…)- on which information may be received.” and that “The printed surface is no longer the analogue of a visual experience of nature but of operational processes”. Similarly, Serra points out that “The fact that the technological processes is revealed depersonalizes and demythologizes the idealization of the sculptors craft”. Both Serra and Steinberg share the same idea that this art is presenting only pure information, and emphasises the importance of the process in art, making the audience realise that the process itself can become the context of the art.

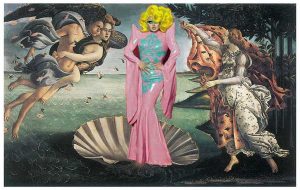

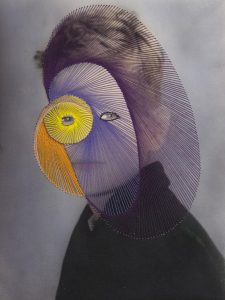

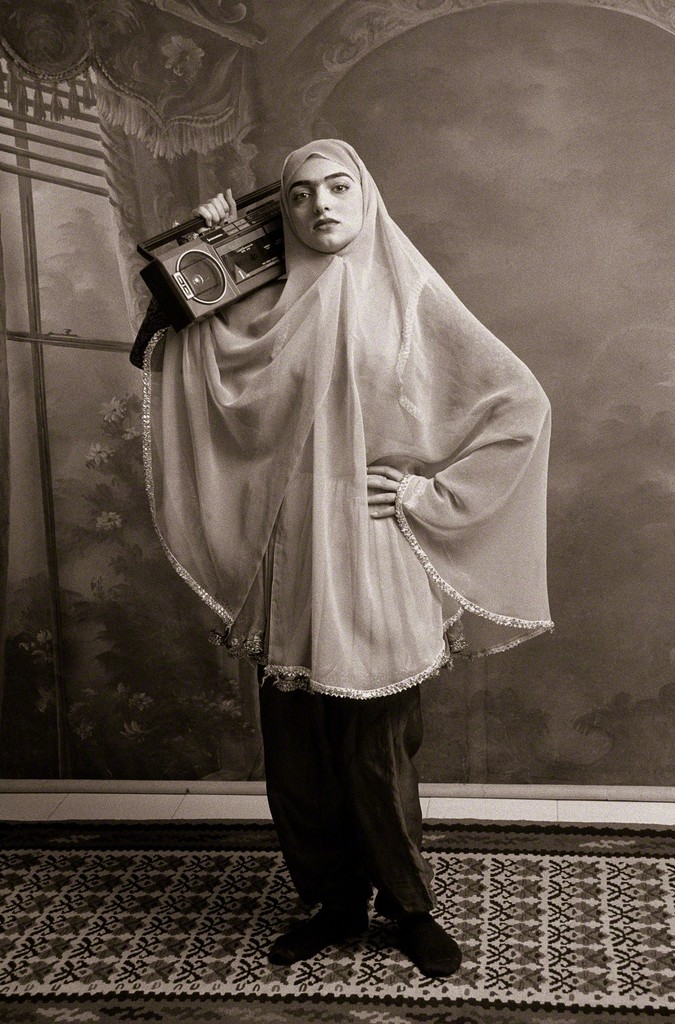

The shift in approach of printing methods such as the Flatbed Press, used by artists such as Rauschenberg, influenced their treatment of the pictorial plane by the no longer need to stick to the traditional ‘head-to-toe correspondence’ and to no longer “create the conception of the picture as representing a world”. For example, Rauschenberg’s works are mainly collages of printed pictures or prints and random streaks of paint, with no depth, they are just images, just information. There is no connection to a relatable world. This shift of the canvas emphasises this idea of the art not being relatable to the body or anything else- “no longer the analogue of a world perceived from an upright position but a matrix of information conveniently placed in an upright position”. A different experience is created through the information being received coherently or in confusion, but however, this range of perception is what makes this shift in approach used by artists so much more interesting- how the work can be read so differently but at the same time cannot and should not be constructed into something else. This opinion is also shared by Richard Serra, how his sculptures should not become a token of the institution, it should be its own piece, and not relatable or recognisable in an outside world.

Harrison, C. and Wood, P., 2003. Art in theory, 1900-1990. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., p.948

Harrison, C. and Wood, P., 2003. Art in theory, 1900-1990. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., p.1124