With the prominent counter culture movement in the 1960’s and 1970’s the arts were exposed to an era of works with a whole new meaning and purpose to the medium that brought new spirit and sensibilities along with it.

Artists like William de Kooning and Jackson Pollock introduced the world to abstract expressionism “characterised by gestural brush-strokes or mark-making, and the impression of spontaneity” (Tate, 2017). This flew in the face of previous ideologies in which paintings where designed as illustrations designed to represent ideas. This new wave created work that would have painters expressing themselves by attacking “their canvases with expressive brush strokes” (Tate, 2017) to illustrate the raw physical passion that they are designed to convey with splatters and splodges unique to the style. Looking at Kooning’s “The visit” we can see these sensibilities being applied within the painting with the organic looking brush strokes and scratches of paint strewn across the canvas.

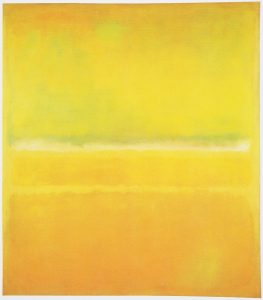

In development of Abstract Expressionism came Colour Field Painting in which artists like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman led the field. In the work “untitled” we can see Rothko’s dramatic use of block colours used in a similar way of expressionism but with “compositions and thinly layered colours” that where “planned deliberately to induce powerful, even spiritual feelings in viewers” (Hodge, 2012). It is with these colours and tones that produce a new spirit to evoke the human psyche to open up and really question its meaning.

Howard Hodgkin’s “Girl on a Sofa” mixes these ideas abstract expressionism with old fashioned values of modernism. Here we see Hodgkin use the sensibilities that come with the Abstract via his mixture of expressive form of the girl that is on the sofa that makes it hard to make out where exactly it is or how the girl is sat. “this is part of Hodgkin’s objective: to inspire recollections, feelings and sensations rather than solid ideas” (Hodge, 2012).

References

Tate. (2017). Abstract expressionism – Art Term | Tate. [online] Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/abstract-expressionism [Accessed 20 Dec. 2017].

de Kooning, W. (1966). The Visit. [image] Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/abstract-expressionism [Accessed 20 Dec. 2017].

Hodge, S. (2012). Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That. London: Thames & Hudson, p.81.

Rothko, M. (1968). Untitled. [image] Available at: https://www.worldgallery.co.uk/art-print/mark-rothko-untitled-orange-and-yellow-1956-206317 [Accessed 20 Dec. 2017].

Hodge, S. (2012). Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That. London: Thames & Hudson, p.85.

Hodgkin, H. (1968). Girl on a Sofa. [image] Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hodgkin-girl-on-a-sofa-p02300 [Accessed 20 Dec. 2017].