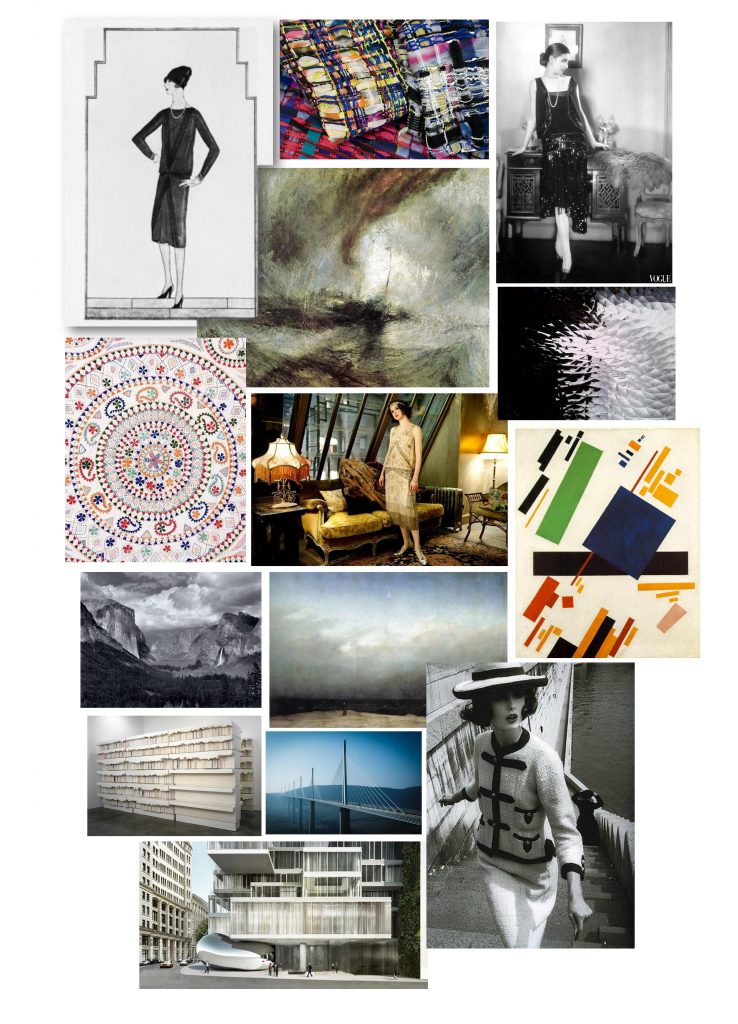

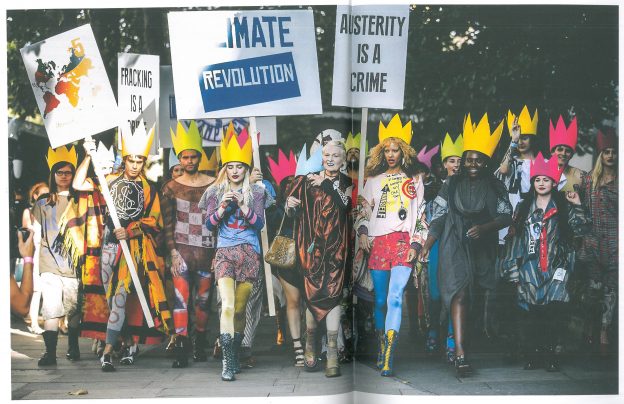

Overall, in my experience, the process of completing tasks one to ten has broadly developed my critical thinking skills. Throughout this module I have become increasingly aware of the complex relationship that exists between fashion and textiles and a wide range of factors including society, history, ethics and philosophy. This improved awareness has allowed me to develop a more analytical mind-set which I feel has already begun to contextualise my practice as a designer. At the start of the module I had already begun to question the paradigm of society in relation to sustainable fashion (as a result of my profound interest in Kate Fletcher’s pioneering work) but I had limited knowledge of other contemporary issues related to fashion and textiles such as gender stereotyping. On reflection, I now have a more informed viewpoint which has opened up more possibility for me to think radically and foster innovation within my visual practice.

I have really enjoyed the research aspect of the module, especially the opportunity to explore my own personal interests within this. For example in several tasks I focussed on the practice of sustainable fashion designers and academics and I have already gone on to integrate this research into my studio practice. In fact, I have begun to define and shape my identity as a designer through deliberately pursuing subjects that inspire me. I noticed that I am especially drawn to using fashion as a tool to question the paradigm of society and I propose to continue tailoring my research in a way that supports the development of my critical thinking and understanding around this. Maintaining an up-to-date awareness of the fashion industry, including the latest advancements in sustainable fashion and textiles, will also support me in becoming a more informed fashion designer with the ability to design within the context of our contemporary society.

One key issue that I had with all the tasks was that I unintendedly complicated the process of expressing my ideas in a written form and this made them overly time-consuming. Despite having numerous ideas from my extensive research, I found it challenging to clearly express myself in an academic style. I noticed that as a result of my preconceptions around academic writing I am very critical of my work so I struggle to express myself quickly. I think this contributed to my incoherent writing style in places because when I am over-thinking each minute detail the clarity of my ideas is often diluted. Furthermore, given that I regularly attempted to use more advanced vocabulary (using a dictionary to look up new words), the process of completing each written task became even more complex and time-costly. As I came across unfamiliar terminology in academic texts and during lectures for example, I compiled my own personal dictionary which I plan to add to throughout my degree. In the short-term this could be seen as an inefficient procedure; however in my opinion the long-term benefits of having this resource will outweigh this minor drawback. To conclude, in future written tasks I propose to comprehensively plan out my ideas so that they are clear and relevant. I will then experiment with writing in a more natural style where my viewpoint can be expressed with clarity, using predominantly my own vocabulary with a selection of new terminology where appropriate.