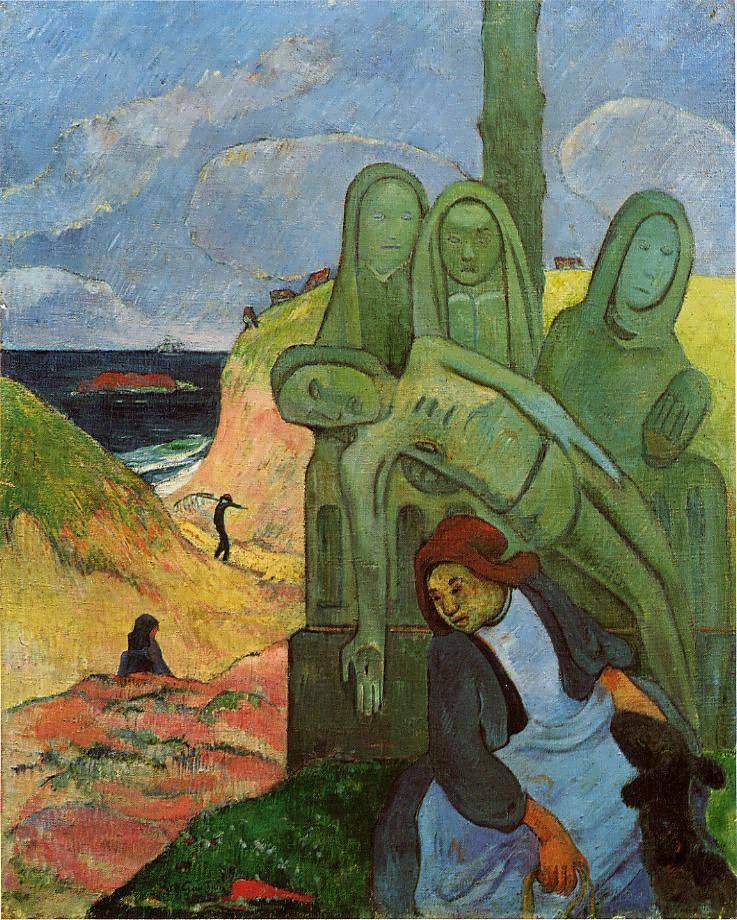

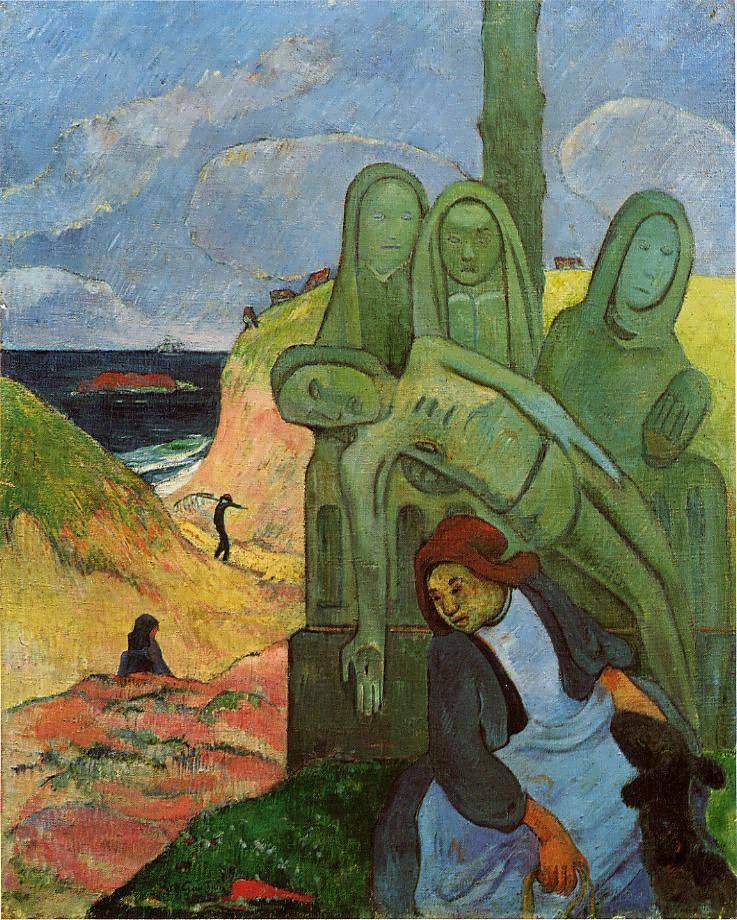

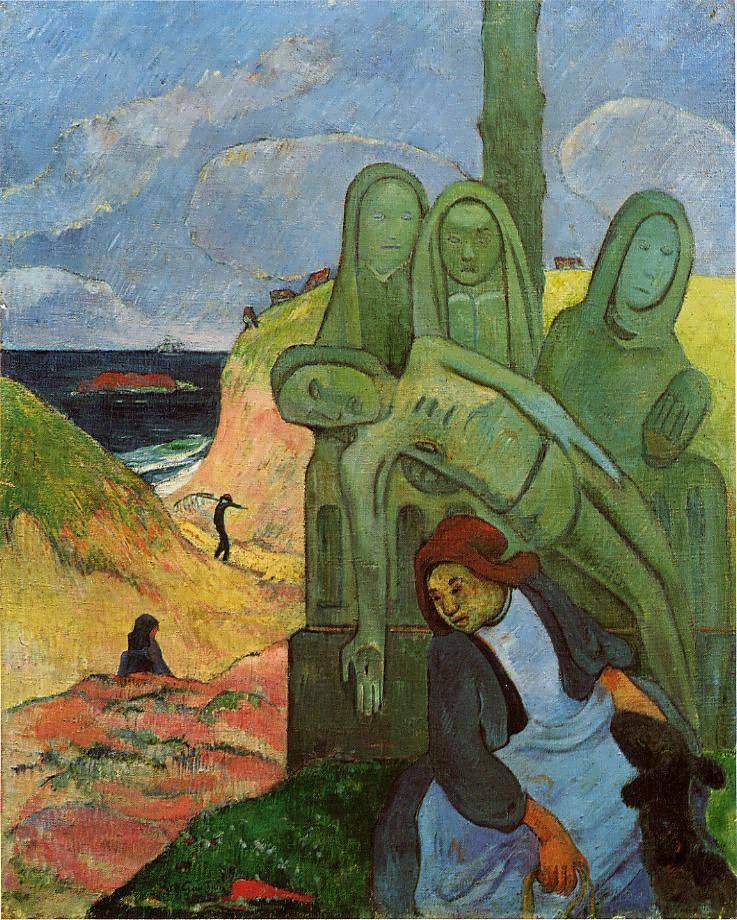

The salient feature of Gauguin’s Green Christ (1889) painting appears in the foreground: the mournful woman sat before a calvary, a sculpture of Christ’s crucifixion. Christ lies on a diagonal, with his arm extending straight down like the pendulum of a grandfather clock, forming a perfect triangular framing of the woman, whose body twists awkwardly.

However, when I saw the painting – in amongst the crowds – at the recent exhibition at Tate Modern I was immediately drawn to the small figure in the middle-distance. A lone, weary fisherman appears between the sand dunes; placed someway between the edge of the sea from where he has come (on the left of the painting) and the route which takes him beyond the picture frame (to the right)). He is returning from a day’s work (though being a fisherman the day no doubt stretches forth for the rest of us); upon his shoulder a rack of fish being the only, though surely significant ‘remains of the day’. I want to suggest this figure is a delicate sighting/siting of the Neutral. To develop this line of thinking I will take a literary detour, with Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day; to help work upon some of Barthes’ observations of a certain ‘neutral’ weariness…

The novelist Kazuo Ishiguro would seem an exemplary writer of the Neutral. His first-person narratives offer poignant revelations, yet generally only through suggestiveness and ambiguity. The pathos he generates typically derives not from a character’s action, but inaction. The narrator of his most well-known, Booker-prize winning novel, The Remains of the Day, is the butler, Mr Stevens. He is surely the epitome of neutrality both in the simple sense of his profession, as someone whose presence must never interfere, and with regards the more complex matter of being unable to reconcile his sense of service with his personal life (specifically his romantic feelings for housekeeper Miss Kenton).

Given Ishiguro’s storytelling is always based in a past history and through a private telling of that past, there is generally a melancholic air to his novels, and in fact his work is often described in terms of the Japanese idea of mono no aware, which literally means ‘the pathos of things’. However, it is easy to be heavy-handed with accounts of melancholia. Mono no aware is also translated as ‘an empathy toward things’ or ‘sensitivity of ephemera’. In Japanese it refers to the awareness of mujo, the transience of things coupled with gentle sadness or wistfulness. Thus there is beauty in transience and not least in the acceptance of transience.

It is easy to see only loss – of love and lives wasted – in Mr Stevens’ final reflections upon the ‘remains of the day’. As Miss Kenton utters the line ‘I get to thinking about a life I might have had with you, Mr Stevens’, it is as if gravity itself is lost. There then follows a seemingly vain attempt to look upon things happily; Mr Stevens seated alone upon a bench declares quietly to himself: ‘I should cease looking back so much … I should adopt a more positive outlook and try to make the best of what remains of the day’. However, the narrative of loss is perhaps too easily overlaid, and for two main reasons. Firstly, for Mr Stevens’ the sense of duty to his profession is genuinely as much a passion as he might hold for Miss Kenton. And in fact both passions are figured with a similar reserved quality; an ardent reserve even. His is an intense, strong quest both to define and live a life of dignity. Secondly, whilst Stevens himself might be said to repress his feelings, the narrative he tells offers insight to a heightened experience, or empathy towards things. There is tremendous beauty revealed through sustained, quiet discernment. His attention to detail: the quality of light, for example, the careful annotation of events and formations. Mr Stevens is attuned to many nuances of his day to day. The closing revelatory sequence, for example, takes place amidst rain and neutral toned light:

The light in the room was extremely gloomy on account of the rain, and so we moved two armchairs up close to the bay window. And that was how Miss Kenton and I talked for the next two hours or so, there in the pool of grey light while the rain continued to fall steadily on the square outside.

It is during this exchange that Mr Stevens considers a weariness that has come over Miss Kenton:

Miss Kenton appeared, somehow, slower. It is possible this was simply the calmness that comes with age, and I did try hard for some time to see it as such. But I could not escape the feeling that what I was really seeing was a weariness with life; the spark which had once made her such a lively, and at times volatile person seemed now to have gone. In fact, every now and then, when she was not speaking, when her face was in repose, I thought I glimpsed something like sadness in her expression. But then again, I may well have been mistaken about this.

The possibility of his having been mistaken is important here. On the one hand, both are older, slower with life. And, as the story unfolds, there is sadness at the root of this relationship. Yet, the uncertainty Mr Stevens notes of here is what allows for a remaining intensity (remnants of the volatile!). Barthes’ identifies a root to weariness that is related to the body (labour, lassitude and fatigue). Labor is, as Barthes suggests, easily associated with the rural and with manual work – it is a word we of course relate to class conditions. Mr Stevens and Miss Kenton are of a working class. They have labored all their lives cleaning and tending to the estate of a landowner. But weariness is harder to place; perhaps if anything, Barthes writes, ‘it is hard to connect … with the worker’s, the farmer’s, the employee’s manual or assimilated type of work’. He suggests the following experiment:

…draw up a table of received (credible) excuses: you want to cancel a lecture, an intellectual task: what excuses will be beyond suspicion, beyond reply? Weariness? Surely not. Flu? Bad, banal. A surgical operation? Better, but watch out for the vengeance of fate! Cf. the way society codifies mourning in order to assimilate it: after a few weeks, society will reclaim its rights, will no longer accept mourning as a state of exception…

What interests Barthes in weariness, then, is that it is not codified. Instead, it:

…always functions in language as a mere metaphor, a sign without referent … that is part of the domain of the artist (of the intellectual as artist) -> unclassified, therefore unclassifiable: without premises, without place, socially untenable -> whence Blanchot’s (weary!) cry: “I don’t ask that weariness be done away with. I ask to be led back to a region where it might be possible to be weary.” -> Weariness = exhausting claim of the individual body that demands the right to social repose (that sociality in me rest a moment … ). In fact, weariness = an intensity: society doesn’t recognize intensities.

In light of these remarks, we might say society does not recognize the intensity between Mr Stevens and Miss Kenton. The book ends, or delivers even this very sign without referent. It is held between these bodies who have labored and grown slow with life, but who equally still bear witness to a ‘neutral’ or unclassified state (‘without premises, without place’) – and this is what they impart still further (hence the intensity of the book itself).

Returning, then, to the fisherman in Gauguin’s Green Christ, I’m wondering if we can now see this neutral weariness in just a mere fleeting scene. There is the juxtaposition of what is heavy and angular in the foreground and the delicate S-bend of the fisherman. His is an existence of labor, he is a ‘tire that flattens’, returning from his work. Whilst in the foreground is the weight of a spiritual (intellectual?) realm. The latter is heavily codified. It inscribes one’s right to think. The former, however, is ambivalent. The fisherman walks away (freely?) from his responsibility (if only until tomorrow). Is he content in his weariness? He seems to lead up to ‘a region where it might be possible to be weary’…

Image-Text-Object: Practices of Research

Image-Text-Object: Practices of Research