Bedour Aldakhil’s PhD research, Saudi females, the abaya and everyday life: Towards a Designerly Approach to Consumers Research, prompted the readings for a seminar on ‘Designerly Ways of Knowing’. She offers an account here of some of the elements of the seminar discussion.

At the start of the seminar, Dr Manghani introduced Noriko Suzuki-Bosco, practicing artist and member of WSA’s alumni, who had joined us for the seminar discussion. Noriko, whose work is explicitly concerned with material form and processes of making, was able to contribute pertinent insights to our reading of two articles by Nigel Cross, ‘Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design As A Discipline’ (1982) and ‘Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design Discipline versus Design Science’ (2001). As part of preparation for the seminar we also listened to an interview on BBC Radio 4’s The Life Scientific with Professor Mark Andrew Miodownik, the British materials scientist at King’s College London and co-founder of the Materials Library.

In the main, the seminar discussions and arguments centred around the earlier article by Nigel Cross. The article lays out an argument for and challenges our thinking about a neglected third area of education: Design. In general, the two dominant cultures of education are the sciences and the arts, broadly defined. Cross’ article published in early 80’s was stimulated by a project on ‘Design in general education’ by Royal College of Arts in the late 70’s, however, it highlights several issues that remain highly relevant to us today.

Cross contrasts between the three cultures science, humanities and design to clarify what he means by design and what is particular about it. As he put it:

The phenomena of study in each culture is

- In the science: the natural world

- In the humanities: human experience

- In design the man made world

The appropriate methods in each culture are

- In the sciences: controlled experiment, classification, analysis.

- In the humanities: analogy, metaphor, criticism, evaluation.

- In design: modelling, pattern-formation, synthesis.

The values of each culture are:

- In the science: objectivity, rationality, neutrality and a concern for truth

- In the humanities subjectivity, imagination, commitment, and a concern for justice

- In design: practicality, ingenuity, empathy, and a concern for ‘appropriateness’.

We recognise that the boundaries between these three cultures are not concrete but fluid. However, one member of the seminar was sceptical about the idea of design vs. science. He felt the design process that Cross argues for puts science in a tight corner. I think what Cross was trying to do is to explain his own perspective and make the case for design by comparing it to science. The underlying argument is that there are ‘ways of knowing’ embedded in the process of design that are different from science; which is specifically illustrated with an example between architecture and science. Drawing on observations from Lawson’s study, How designers think (Architectural Press, 1980), Cross explains how postgraduate students of architecture and science show ‘dissimilar problem-solving strategies … The scientists generally adopted a strategy of systematically exploring the possible combinations of blocks, in order to discover the fundamental rule which would allow a permissible combination. The architects were more inclined to propose a series of solutions, and to have these solutions eliminated, until they found an acceptable one’. Lawson elaborates further:

The essential difference between these two strategies is that while the scientists focused their attention on discovering the rule, the architects were obsessed with achieving the desired result. The scientists adopted a generally problem-focused strategy and the architects a solution-focused strategy. Although it would be quite possible using the architect’s approach to achieve the best solution without actually discovering the complete range of acceptable solutions, in fact most architects discovered something about the rule governing the allowed combination of blocks.In other words they learn about the nature of the problem largely as a result of trying out solutions, whereas the scientists set out specifically to study the problem. (Lawson, How designers think, 1980)

Thus, for Cross, science relates to a process of a linear analysis to find a solution, while a designerly way of knowing is a process of synthesis and iteration. It unfolds in the future with innovative realisation. The designerly way of knowing is not only embodied in the process of designing but equally the products of design also carry knowledge. The material culture of our world provides knowledge to everyone ”…one does not have to understand mechanics, nor metallurgy, nor the molecular of timber, to know that an axe offers (or ‘explains’) a very effective way of splitting wood”. In a similar vein Professor Mark Miodownik from University College London, in the interview on BBC Radio 4’s The Life Scientific, argued for the importance of our material culture and its sensual aspects. He offers the radical idea of converting public libraries into workshops with laser cutters and 3D printers in place of books. His point is that we now can access books with little difficulty (and on different formats) but materials and technologies in the context of a workshop are not widely available. Through making, doing, and experimenting people understand and have more appreciation for materiality and could find new solutions for problem that exist in our world. Materials have there own sensibility different from writing and reading.

Today we can see how people use technology creatively to solve their own problems and help learning from each other. The creative use of hash tags in twitter, or the rise of virtual communities are just a couple of digital examples. Maybe it is appropriate to end with a quote from Victor Papanek, a philosopher of design, from his book Design for the Real World:

“All men [and women] are designers. All that we do, almost all the time, is design, for design is a basic to all human activity. The planning and patterning of any act towards a desired, foreseeable end constitutes the design process and attempting to separate design to make it a thing by itself works counter to the fact that design is the primary underlying matrix of life” (1972: 3).

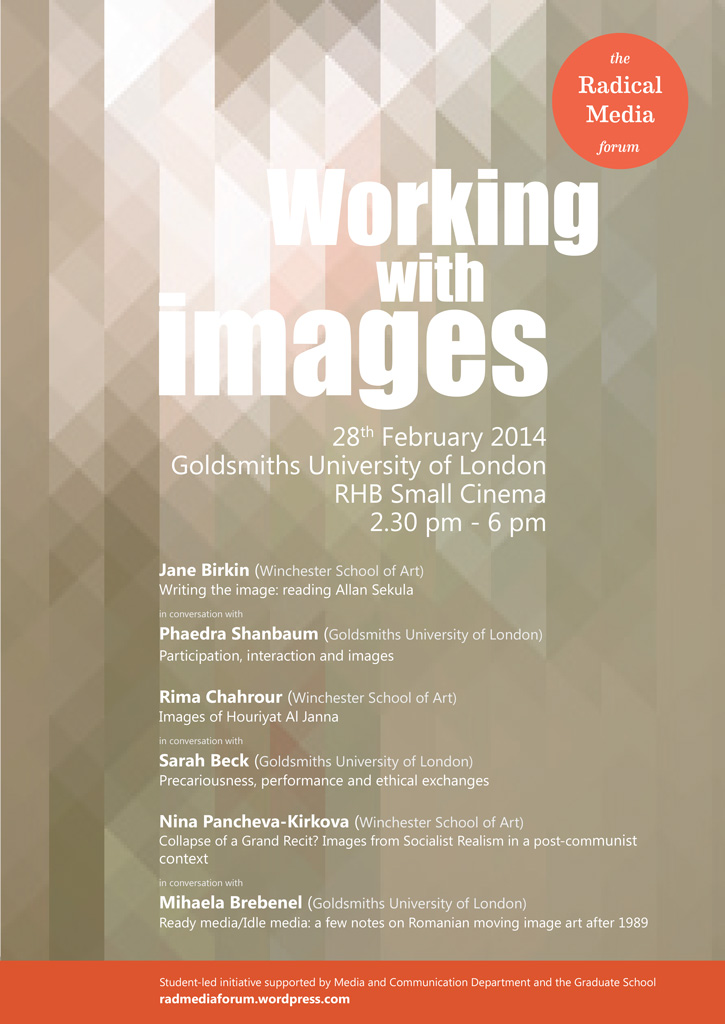

Image-Text-Object: Practices of Research

Image-Text-Object: Practices of Research