Jason Kass recenlty completed his PhD at Winchester School of Art. The title of his thesis is ‘Cognitive Aspects of Pictorial Address and Seriality in Art: A Practice-led Investigation’. In this post he offers an overview of the nature and scope of his research.

My doctoral research explored the perceptual and cognitive processes that underlie spectatorship of pictorial artworks and incorporated insights into the production of new works of art. The fundamental premise of my research was that artworks exist as part of the visual world and are subject to the same visual processes as ordinary scenes and objects. Applying existing empirical findings from cognitive psychology to spectatorship of works of art allows for a more complete understanding of pictorial address.

Using theories and methods from psychology to understand the experience of artworks is not in itself novel. The field of empirical aesthetics boasts a wide literature comprising experiments around aesthetic preference and art appreciation. My research differs based on my position as a visual artist rather than a scientist and my emphasis on relating psychological findings to existing art theory and art historical narratives. The incorporation of practice-based research in the form of producing new works of art (Fig. 2) also brings a different perspective to an established yet often divisive discipline.

Within the thesis, I focused on seriality as an aesthetic strategy and the mode of address offered by serial works of art. Serial artworks have previously been theorised, in particular by Coplans (1968), who established a distinction between serial artworks that comprise multiple discrete but related instances and pictures produced along the masterpiece model. Fer (2004) has said about seriality, “It brings with it a whole set of assumptions about the nature of aesthetic experience as direct and spontaneous” (p.4).

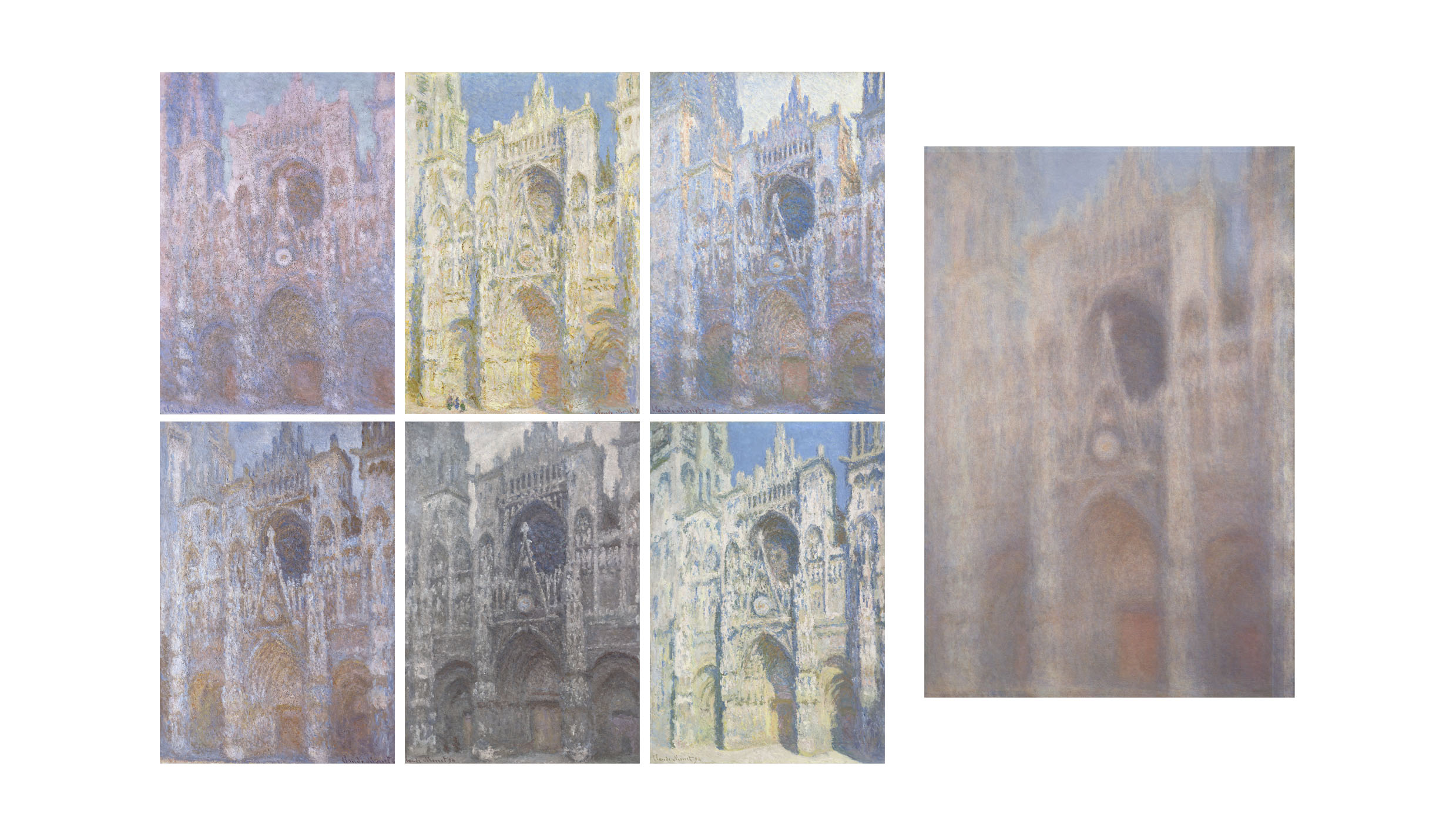

My research sought to reveal the direct impact of seriality on the experience of the viewer by way of cognitive and perceptual processes. In the first instance I considered Monet’s painted series of the Rouen Cathedral. A proto-serial artwork, Monet understood the importance of exhibiting the nearly thirty paintings depicting different light and weather conditions being exhibited together.

I consulted theories of concept formation and face recognition that speak to the ability to form a stable mental concept from a set of varied instances: a feature essential to navigating a complex visual world. Findings within the study of face recognition indicate that the process may involve retaining invariant information across instances while eliminating extraneous superficial details; a process akin to averaging (Young & Bruce, 2011).

Applying this same premise to Monet’s cathedrals it is possible to infer that the variation in colour and luminosity across the paintings prompts the viewer to form a stable mental concept that lasts long after the in situ viewing (Fig. 2). With regard to art historical narratives, this implies that Monet’s series are as much conceptual as they are perceptual in nature, which runs counter to Duchamp’s well-known exclamation of Impressionist artworks as purely retinal in nature (Krauss, 1990; de Duve, 1996). I explored these findings through photography, drawing and found images (Fig. 3).

The second case study examined Warhol’s use of serial repetition in works from his Death and Disaster series that repeat a gruesome image multiple times across a single canvas. Warhol said, “when you see a gruesome picture over and over again it doesn’t really have any effect” (quoted in Goldsmith, 2004, p.19). He presumed that repeated exposure to an distressing image results in a ‘deactivating’ of the negative affect.

Employing existing psychological findings regarding repeated exposure (Zajonc, 1968) it is possible to infer that viewing artworks from the series ultimately leads to an increase in negative affect for the viewer, despite an initial increase in positive affect as a result of repetition. This is due to increased access to the negative semantic content, also a result of repeated exposure (Reber et al., 2004). Related ideas were explored through practice-based research responding to Hunter’s (1973) ”aesthetics of boredom” (Fig. 4).

Through future research I hope to build on my dissertation as a model for the exchange of ideas between experimental psychology, art theory and art practice. Although within the dissertation I did not conduct original empirical research I believe there is scope to expand on the theoretical frameworks that I developed through experimentation. I am also keen to further disseminate my findings through practice-based research resulting in creative outcomes that can be publically exhibited.

List of References

Barthes, R. (1981). Camera lucida: Reflections on photography. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Coplans, J. (1968). Serial imagery. Pasadena: Pasadena Art Museum.

De Duve, T. (1996). Resonances of Duchamps Visit to Munich. In R. Kuenzli & F.M. Naumann, Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press.

Fer, B. (2004). The infinite line: Re-making art after Modernism. Hartford: Yale University Press.

Goldsmith, K. (2004). I’ll be your mirror: The selected Andy Warhol interviews 1962-1987. New York: Caroll & Graf Publishers.

Hunter, S. (1973). The Aesthetics of Boredom. In S. Hunter and J. Jacobus eds. American Art of the 20th Century: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Krauss, R.E. (1990). The story of the eye. New Literary History, 21(2), 283-298.

Reber, R., Schwarz, N. & Winkielman, P. (2004) Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(4), 364–82.

Sagner-Duchting, K. (2002). Monet and Modernism. Munich and London: Prestel.

Young, A. W., & Bruce, V. (2011). Understanding person perception. British Journal of Psychology, 102, 959–74.

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2), 1–27.