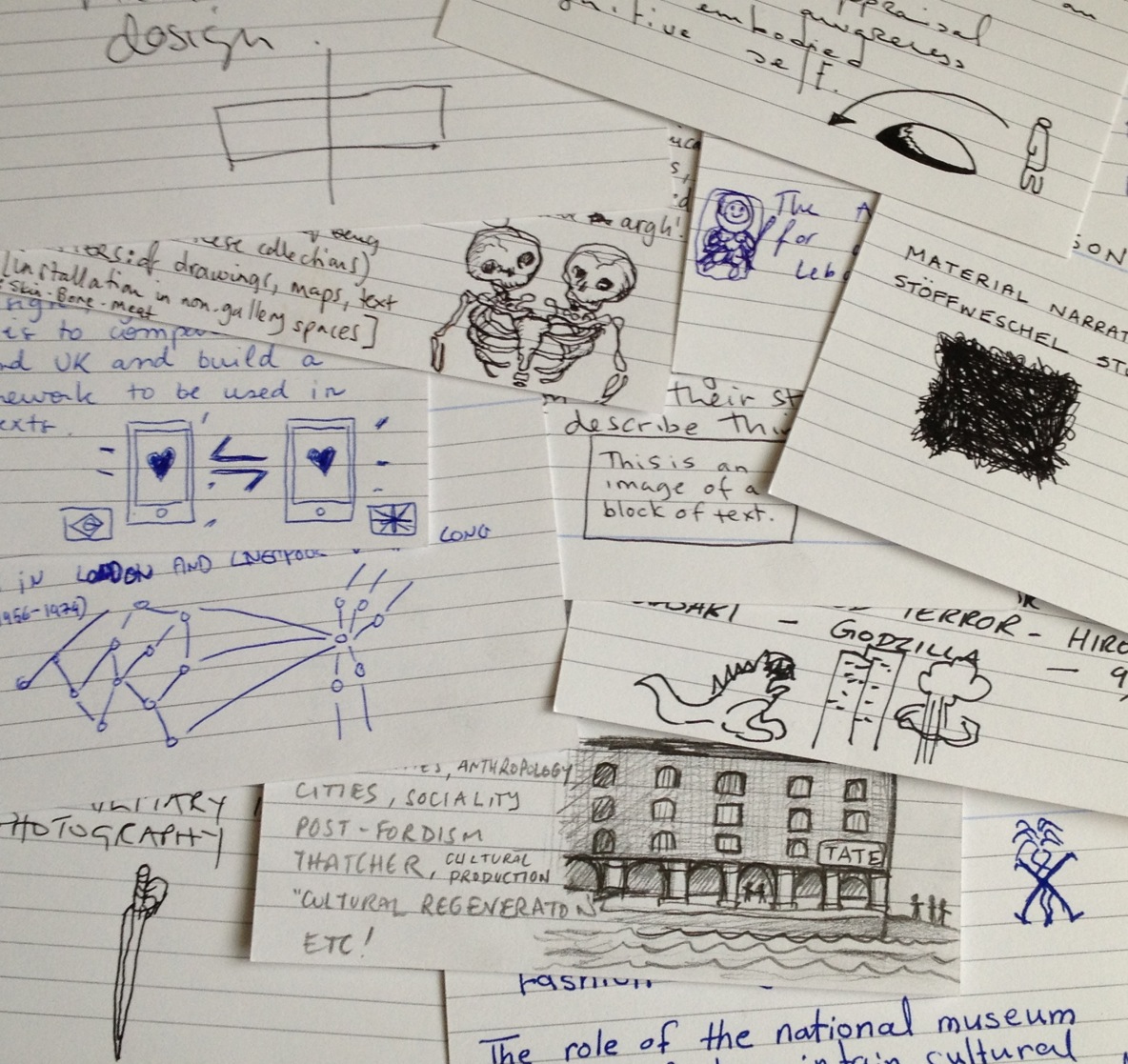

- If you were asked to make a sketch of your research interests what would you draw?

In the opening session of The Seminar, we began by first hearing each other’s research interests. We are all at different stages of our research, and inevitably there is a wide range of research projects. Interests span from material narratives (of Stöffweschel [stuff exchange]), the Arab-Muslim doll, interface designs, mapping remains, game designs, the geo-cultural mapping of cultural producers, units of description, the motif of the monster vis-a-vis incidents of terror and war, creative communities, display of traditional clothing, the changing face of masculinity, and much more besides… (it is quite a list!)

It was wonderful to hear everyone speak about their own research and subsequently to share in a debate around the nature of the PhD, and the different kinds of engagement and approaches we each reveal. I was particularly interested to foreground the word ‘philosophy’ in the title PhD, i.e. a doctorate in philosophy. What is this ‘philosophy’ that we will all end up sharing in obtaining the PhD? It is not that we are studying the subject of philosophy (though some of us will dabble with this domain), but technically, we are all engaged in a form of philosophy, as in a mode of enquiry, investigation and contemplation.

I talked briefly about the origins of the Western philosophical tradition, which arguably still underpins institutional rhetoric today. Philosophy is the ‘love of wisdom’, and Socrates and Plato, for example, took it to be an underlying enquiry into what it is to lead a ‘good’ life. I wanted to suppose this remains a integral part of what we do when undertaking doctoral research. We’re not just interested in a singular problem (i.e. our research topic/subject matter), but a wider set of connections and relationships. We are placing our research in a communal intellectual space. It might not always feel like that when we are working alone on our writing, reading, making, thinking; indeed the PhD can be lonely at times and/or require good doses of solitude. Nonetheless, there is a continuum of intellectual practice that we are part of, which is the ‘philosophy’ named in our PhD.

Ancient Greek philosophy was interested in objects, those that remain the same (plants, animals, seasons, stars etc), and those that vary (language, customs, laws, politics). Today of course, much of what we once thought ‘remains the same’, have proved highly changeable, and we have created the means to change such objects through our investigations (for good or ill!). The physis (nature, that which is fixed) has proved just as complex and changeable as nomos (culture), but we could never have known these things without some kind of investigation and experimentation. Aristotle adopts the terms theoria (theory, contemplation) and praxis (practice) to evoke the idea: (1) of the intellects ability to ‘take hold of’ and categorise the world around us, and to articulate ideas about it; and (2) voluntary human activity, whereby we choose to alter what can be changed. Today, we can all too often hear of a divide between theory and practice, yet this would hardly seem to pertain to the curiosity and inventiveness of those early days of philosophy.

The reading I gave for this first session was the introductory chapter of Woodhouse’s ‘A Preface to Philosophy’, which is a slim ‘textbook’ for someone taking a philosophy degree. It struck me this prompted some useful debate. On the opening page, Woodhouse asks the question, ‘What is it that makes a certain question or claim philosophical?’. As he adds, this is not an easy question to answer. I think, however, it is a useful question to have in your research toolkit. What is it that makes your work ‘philosophical’? By which I mean, what is it that makes your work questioning, critical and reflective? Woodhouse offers his own definition: ‘Philosophical problems involve questions about the meaning, truth, and logical connections of fundamental ideas that resist solution by the empirical sciences’. This was inevitably – and rightly – met with quite a bit of challenge among those in the room. I think we are all attuned to countering the very notion of fundamental ideas. But what are the galvanising Ideas that we rest our work upon? What happens if we seek to challenge these ideas? Perhaps your work needs to be sustained by certain key – if not fundamental – ideas. For example, what do we each take to mean as ‘society’ and the ‘individual’, or the notion of ‘experience’? Psychoanalysis pertains to specific notions of the individual in a way that is very different to Marxism. When these combine, particularly in the work of the Frankfurt School (in the early twentieth century), we get further configurations and complexities. Perhaps you might be working between such terms. You need to think about what this might mean and where it takes you in your thinking; equally we need to consider how we can suitably present our ideas to account for such collisions and reconfigurations. Of course, it might be in challenging certain ‘fundamental ideas’ in our own research that we find things become unstable, unworkable even! …this can be disconcerting, yet it can also be the opening towards a whole new depth and breadth to the work.

A further problem arising from Woodhouse’s definition was the positioning against ’empirical science’. I think there is something attractive for the areas of art and design that philosophy is somehow seeking to go beyond the immediate, the visible, the uniformly testable. But, I think we were in danger at times in our conversation to allow an unnecessary division between art and science. We did discuss this directly, which helped us keep on track, but it raises an important point about the way in which ‘knowledge’ has been turned into specific discourses of knowledge. The chapter by Woodhouse might feel to many of us as too prescriptive, too logical. Yet, I hope it served to keep alive certain ways of understanding how we approach ‘philosophical’, or research problems. It is useful to define how different ideas, elements, and engagements do or do not bear equivalence. Woodhouse talks in terms of ‘assumptions’ and ‘consequences’, for example. How might we understand the logical or ‘argued for’ distinctions between various assumptions and consequences in our own field of study? At the end of the chapter, Woodhouse provides a little ‘shopping list’ of the divisions of philosophy, which include: logic, ethics, metaphysics, epistemology, aesthetics, politics, religion, science and history. These are rather ‘big’ terms, and I’m sure we’ll touch upon many of them in subsequent seminars, but for now it is perhaps worth keeping some of these terms to mind, to ask ourselves, not only what our research is about (and/or what it hopes to be about), but what kind of philosophy we bring to it, claim for it, and take from it…