I recently visited Tate Modern’s collection display, Photographic Topologies, which brought together the work of artists whose use of photography presents a systematic, or ‘topological’ approach. Typically, these works show multiple images of similar subjects. On display were portraits of Thomas Ruff, Rineke Dijkstra and Paul Graham, and architectural subjects in the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, Thomas Struth and Hiroshi Sugimoto. Through repetition these artists reveal subtle contrasts and similarities in their subjects.

Of course the typological method is most well known for its pioneer, the German photographer August Sander (1876-1964); whose work I specifically went to see. Examples ran along the central gallery, taken from Sander’s seminal ‘People of the Twentieth Century’, a vast collection of portraits documenting the society of the Weimar Republic according to profession and social grouping. It was great to see them up close. Many times I have looked at the ‘stiff’, ‘self-importance’ (to borrow Barthes’ words) of Sander’s Notary as it appears neatly on a page in Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida. The portrait shows a figure in a hat and buttoned-up coat, holding a cane. He stands before a brick building with a curved flight of steps and stares blankly away from the camera, perfectly perpendicular to that of a dog who stands before him. Given that Barthes in the relevant passage writes how the ‘Photograph of the Mask … [is] critical enough to disturb’ and that ‘[p]hotography is subversive …when it is pensive, when it thinks’, I have frequently considered the strict, cool-eyed work of Sander to relate in some kind of ‘zero-degree’ seeing. Indeed, according to the curator’s notes, ‘Sander’s process of analysing and ordering his images was matched by the rigorous, objective style of the photographs themselves. All of his subjects are observed by the photographer with the same neutral distance’.

Sander, then, has always been on my list of artists to include in a study of ‘zero degree seeing’. As I stood there in the gallery, peering at the pictures framed on the wall, I was still inclined to link Sander to the Neutral, yet not in the way I had first imagined… Let me first state the case for my original thinking on Sander’s work. Before coming to Barthes’ The Neutral, I had long thought about how images, and particularly photography, might be considered to undo categories and structures of meaning. I’ve read the passage on Sander in Camera Lucida countless times and every time I seem to have come away with a slightly different view. Even in itself, this suggested to me something about how ‘the image’ unmoors our thinking in ways that are seemingly productive, even cohesive, yet without properly ‘fixing’ (the word here has a nice irony since photograph are – or at least used to – ‘fixed’ in the darkroom to stop them from simply fading away). At the close of Camera Lucida, Barthes suggests in an epic, final line that there are two ways to look at the Photograph: ‘The choice is mine: to subject its spectacle to the civilized code of perfect illusions, or to confront in it the wakening of intractable reality’.

Turning back to the passage on Sander, we can start by thinking that here is an example of pure, intractable reality. Barthes suggest this is in a sense the reason why Sander’s work was censored at the time, being ‘critical enough to disturb’. Sander’s photographs have no come-back. They are directly what they show. The notary, for example, is exactly as shown – yet in being shown, we suddenly realise we don’t know what this means. The code of perfect illusions is immediately revealed as a code and bursting through is the intractable reality of the man in the photograph, who we soon start to know less and less. Barthes remarks that in the commercial sphere ‘no meaning at all is safer: the editors of Life rejected Kertész’s photographs … because, they said, his images “spoke too much”; they made us reflect…’. The question is: does Sander’s work make us reflect? ‘Photography is subversive,’ Barthes argues, ‘not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks’. I have always looked upon the Notary as the embodiment of this ‘pensive’ image. We do not know what the man is thinking, but we believe he is nonetheless. He stares firmly into the distance, though seemingly at a brick wall (which perhaps adds to the strength of his stare). His hands are clasped tightly too and the dog adds further ‘bite’ to the composition. The notary’s stare then becomes our own as we start to think about the meaning of the image; why it was taken, who this person might be and what significance he holds.

This, I feel, is the effect of moving between the pages of Camera Lucida, and in many ways has remained my way of thinking about Sander, whether I like it or not! Yet, looking again (and again) at the text, Barthes is actually quite clear. He considers him a ‘great mythologist’, but whose work ends up an aestheticisation of the political:

Sander’s Notary is suffused with self-importance and stiffness, his Usher with assertiveness and brutality; but no notary, no usher could ever have read such signs. As distance, social observation here assumes the necessary intermediary role in a delicate aesthetic, which renders it futile: no critique except among those who are already capable of criticism.

Not only then a highly constructed image, but indeed a ‘spectacle’ which we submit to the ‘civilized code of perfect illusions’. Surely then, too full of ‘paradigm’ for anything of the Neutral?

One of the prints in the gallery was Sander’s ‘Victim of Persecution’ (c1938). He is a neat, well-to-do man. There are no immediate signs of being persecuted (though of course that is what the picture questions in itself). The man is a little sullen, and the framing of the image (the upper torso and face turned slightly to one side, his eye-line a little raised) evokes for me a man in the dock (though perhaps I’ve seen too many courtroom dramas!), yet there is really so little to go on. Yet what struck me was the feeling of a certain benevolence. The directness of the photograph and the succinct title gives no reason other than to believe this person is who they say they are. The man looks benevolent and I feel similarly towards him. But what do I mean by benevolence in this case? The man is not ‘real’ for me and I will never have to prove my benevolvence. He is only an image. He does evoke reflection in me, though in no way is this something I can easily articulate. If it were simply a ‘kindly feeling’ I held towards the image/this man it wouldn’t necessarily be of interest. In The Neutral, Barthes distinguishes between ‘dry and damp’ benevolence. Damp benevolence is ‘on the side of demand: “kindness” … diffuse aura of amiability’; so being the more common-place meaning of the word. Dry benevolence, however, refers to Taoist thinking: ‘A stiff benevolence, because rooted in indifference. For the sage, everything is equal. Refrains from exerting a function’.

Looking at the series of the photographs in the gallery, what I saw was simply a ‘batch’ of photographs. The stiffness, the exactness, the pensiveness – all as we associate with Sander – was not matched in the physicality of these prints. Some lacked focus, others the edges were not strict. I did not feel in the presence of some ‘intractable reality’ – there was nothing to puncture my world. However, these were not ‘tame’ images either. At the close of Camera Lucida, Barthes complains of a consumption of images, as some kind of ‘nauseated boredom, as if the universalized image were producing a world that is without difference (indifferent)’. On this count, what I saw in the images – as refraining ‘from exerting a function’ – would seem to place them under Barthes’ critical eye, so as to ‘subject spectacle to the civilized code of perfect illusions’. But I would prefer to appropriate his reading of a dry benevolence. As I stood in the gallery, wondering what to make of the photographs, wondering if others around me could see more than I might, I tried to grasp at what the sage might see: a radical vision, in which ‘everything is equal’. Standing before these photographs perhaps many of us could repeat Barthes thoughts: ‘I feel this “benevolence” for people who are such strangers to me that I have no occasion for internal conflict with them = total and peaceable incommunication’.

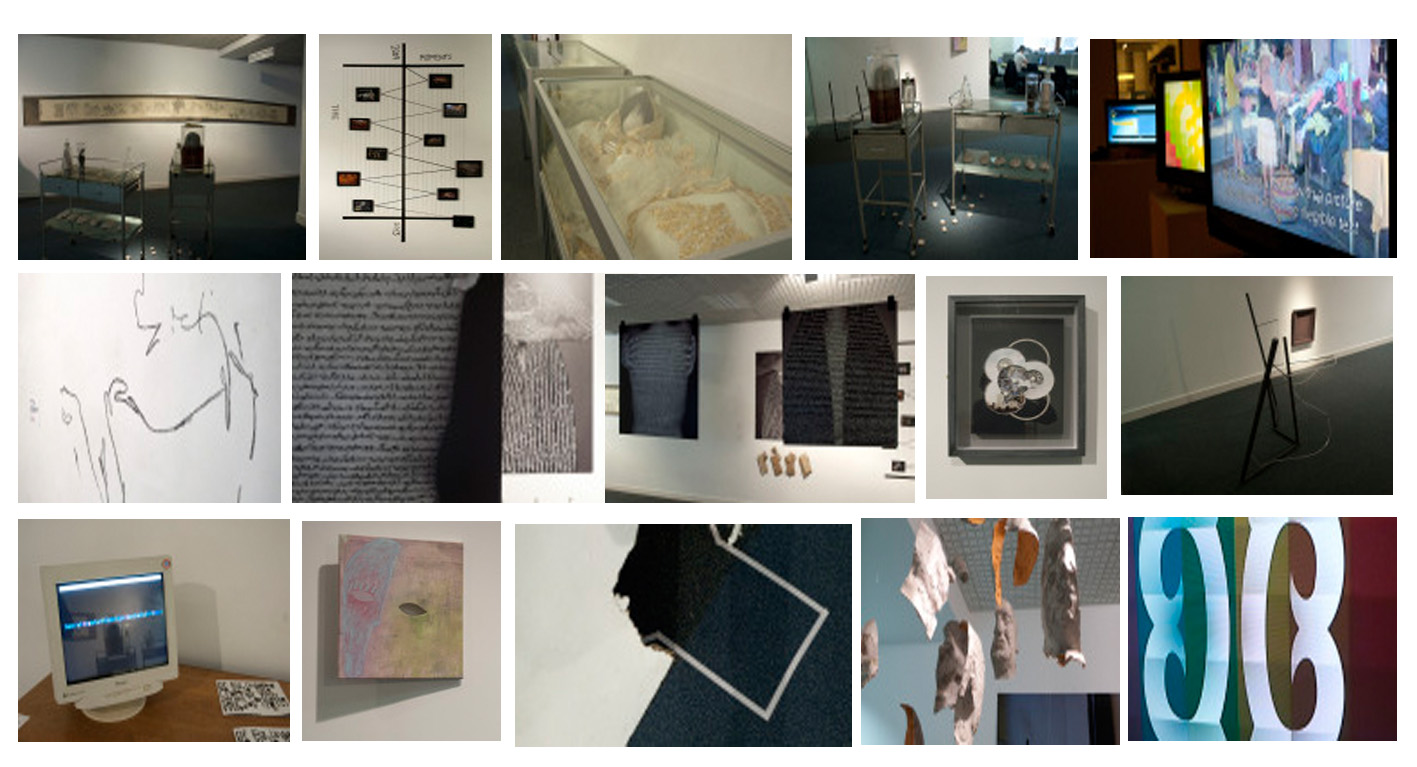

Image-Text-Object: Practices of Research

Image-Text-Object: Practices of Research