Recent PhD alumna Noriko Suzuki-Bosco and current PhD student Lesia Tkacz recently ran a fantastic workshop which introduced participants to computer-generated novels. Below, Noriko shares some details.

PhD student Lesia Tkacz asked me to help her design and organise a computer generated novel workshop. I suggested that the workshop should be collaborative, and together we designed it so that the participants would be able to work with us as fellow authors. The workshop was for the Human Worlds Festival which the University of Southampton was running as part of the UK’s national Being Human festival in November. I didn’t know anything about computer generated novels but I really enjoyed working with Lesia for the Lockdown Larder Cookbook project, so I said yes. The aim of the workshop was to create a ‘mash-up’ style generated novel using a program that Lesia would write. Participants would select texts which would then be computationally processed to produce the generative novel. I liked that the collaborative element of the workshop would further complicate our thinking around the roles of the author and of the machine. I also thought the whole process sounded a bit like making a communal stew, which made it seem accessible, even for a non-technical person like me.

What is a computer generated novel?

All computer generated texts can be algorithmically produced from data such as images, spreadsheets, or other texts. Computer generated novels are a form of creative text generation because the programmer has prioritised creativity over functionality. Prioritizing creativity often results in generated texts which can contain surprises and unusual use of language. Generated novels are therefore different from more practical computer generated texts like the weather, sports, finance, and election reports we read in news media, because the latter prioritise factuality, grammatical coherence and clarity while often ignoring creativity.

Indeed, when Lesia showed me an example of a computer generated novel, I was slightly taken back by its strangeness. Lesia explained that this was because language processing technology was still very limited when compared to the traditional ‘human’ written texts which have interesting narratives, rich character development, and can sustain semantic coherence. In recent years, however, creative text generation has been gaining attention in digital culture where it has been used for creative experimentation with language and with AI tools, for cultural critique, expression, for comic entertainment through chance and absurdity, and for parody and pastiche through the computational altering or remixing of literary works.

Furthermore, Lesia described that current computer generated novels were not meant to be ‘read’ in the conventional way from start to end. Rather they should be read in bits or skimmed through, picking up any interesting or intriguing sentence structures or word combinations. As I scanned through the text and skipped from one section to the next, I found myself creating my own rhythm of ‘reading’ and warming to the weird but strangely addictive generated texts.

The WSA Computer Generated Novel Workshop

We decided to offer an extra workshop session for the PGR community at WSA as we thought it would be fun to involve them in the process of creative text generation and to engage in conversation around this emerging form of literature.

The workshop would produce a 50,000-word computer generated novel that would be entered into the National Novel Generation Month (NaNoGenMo) 2020 challenge. NaNoGenMo is an annual online challenge which asks participants to use computer code to generate a work of 50,000 words or more.

Six people signed up to take part in the WSA session. They were asked to watch a lecture about generative text creation prior to the workshop and to select one or more texts from Project Gutenberg that would become computationally processed to create the generated novel. We asked them to select text(s) that resonated with the idea of ‘being human’ to reflect this year’s Human Worlds Festival theme ‘Being Human as Praxis’.

Here is the list of the texts that were selected:

- Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

- The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

- An Honest Thief by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

- The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

- Kawidan by Lafcadio Hearn

- The Works of Edgar Allen Poe (Vol. II)

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

- Grimm’s Fairy Tales by Brothers Grimm

- The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication by Charles Darwin

The list shows the varied nature of the texts but interestingly they fell into three general themes – human behaviour and experience, the supernatural, and the animal.

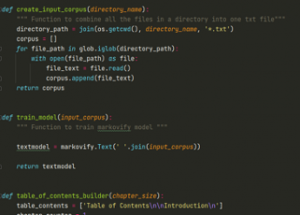

During the workshop, Lesia shared the computer programming code that she had written using the Python programming language and the Markov chain tool Markovify to demonstrate what actually happens behind the scenes when we say, ‘the computer is processing the text’.

Six different versions of the generated novel were produced and the participants spent a little time ‘reading’ through the texts to decide which was to be their final version to enter the NaNoGenMo 2020 challenge.

Discussions around authorship and creativity ensued as we questioned whether the resulting text was human or machine authored. The collaborative nature of the workshop further complicated this query. The unconventional ‘reading’ experience also generated dialogues on practices of reading. ‘Are we reading?’, one participant asked. We wondered whether we were making concessions to the machine because we were trying to make sense of what we were reading. I also noticed the participants making more references to visual and sensory forms of interactions whilst engaging with the generated text.

At the end of the workshop, a collective decision was made as to which version of the generated novel would be entered to the NaNoGenMo 2020 challenge. A title, configured from words in

the text that caught our attention, was also given. We also agreed that all of the participants’ names would be acknowledged as ‘authors’ to highlight the collaborative nature of how The Apollo and the Dragon-King: wild and semi-wild rabbits came into being.

Book Launch

The Apollo and the Dragon-King: wild and semi-wild rabbits was entered to the NaNoGenMo 2020 challenge and we felt that we should have an official book launch to celebrate. We invited all of the authors to come to the book launch dressed up in the character from their chosen text(s) or inspired by the mash-up nature of the final text.

After the opening speech, the link to the submitted novel was shared. This was followed by Lesia’s dramatic reading of excerpts from the novel and a game of textual scavenger hunt where we had to find as many references to animals as we could in 3 minutes. The scavenger hunt was great fun and, interestingly, it also made us reflect on alternative ways to engage with text. ‘Maybe generated novels should be read in a group’, pondered Lesia.

Lesia and I are hoping to create a physical version of the generated novel, which may also give us opportunities to engage with the text in material ways. What if we drew pictures, made comments in the margins, rearranged the paragraphs or attached additional pages?

How would our interventions into the material matters of the book influence our reading of the computer generated novel? Would it affect how we think about the role of the author and machine?

I think Lesia and I will have to have a little chat to see how we can come up with another project to take these ideas further.