Richard Acquaye’s PhD research explores Sarat Maharaj’s concept of “Know-how and No-How: stopgap notes on “method” in visual art as knowledge production” as a barometer to examine the idiosyncrasies of practice in indigenous West African fabric production and their diverse culturally embedded significance. His work seeks to develop and advance the possibilities for commercial application of indigenous West African textiles in middle to high end interior textiles globally. Richard presented the follwowing paper at The First Global Creative Industries Conference that was hosted by the Global Creative Industries Programme of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Hong Kong from 17th to 18th April 2015. The conference was themed ‘From Culture to Business and Vice Versa’. Conference participants addressed a breadth of issues in the study of the creative industries from various viewpoints including anthropology, business studies, communication, creative arts, culture, economics, education, environment, film, media and sociology. The conference also espoused the interaction and integration between academia and industry on the prospect and sustainability of the creative industries. In addition to the panel and individual paper presentations, a roundtable workshops and other creative forms of communication platform where created to engage scholars and practitioners in a series of dialogues. A major highlight is a cross-disciplinary scholarly collaboration and discussions.

Cultural Ownership and Appropriation

Sourcing Fabric Design Ideas from ‘Indigenous’ West Africa

Artist from many cultures are constantly engaging in cultural appropriation. Picasso famously appropriated motifs which originated in the work of African carvers. Painters who are members of mainstream Australian culture have employed styles developed by the aboriginal cultures of Australasia. The jazz and blue styles developed in the context of African-American culture have been appropriated by non-members from Bix Beiderbecke to Eric Clapton. (J. Young, 2010)

The paper interrogates complexities of appropriation, cultural and indigenous ownership and their implication for the production and commercialisation of indigenous West African fabrics. It draws on the ‘Maori Tattoo’, ‘Volkswagen-Tuareg SUV’ and ‘Northwest Coast Native American Potlatch’ appropriation controversies and makes a case for a system that will allow the use of cultural works as reference for textile designs without necessarily provoking protests and disapproval. These controversies may not be directly linked to textile production; however, their implication cast a shadow on certain patterns in West Africa. And hence, some equivalents were drawn between the situations in textile fabric production in the region and that of the above controversies. This study further suggested a process modelled on the principles of the ‘Creative Commons’ that will allow for greater access to the knowledge and culture for informed access and acceptable usage of West African indigenous textile design references. It hypothesises that sharing that knowledge and creativity with the world will engender new design ideas and by extension provide mutual benefit for both ‘cultural owners’ and users.

Cultural and Indigenous ownership and appropriation disputes have such an amorphous dimension in West Africa. Of course, this is not isolated as there are contestable issues of such nature in even developed countries such as Canada, Australia and USA. The situation in West Africa is part of a regional African phenomenon as captured by Jennings (2011) “the history of fashion in Africa is one of constant exchange and appropriation, a complex though ill-documented journey with different influences coming into play across time and place.” It is instructive to posit then that the subject of ownership could be very debatable. Cultures develop around foreign commodities and seep so deeply into the social fabric such that origins of those commodities are forgotten entirely. Invariably, cultural practice appropriates alien or exotic, peripheral or obsolete elements of discourse into its changing idioms and this very perception further crystallised the complexities of appropriation. (Buchloh 2009; Sanders 2006).

Customary Narrative

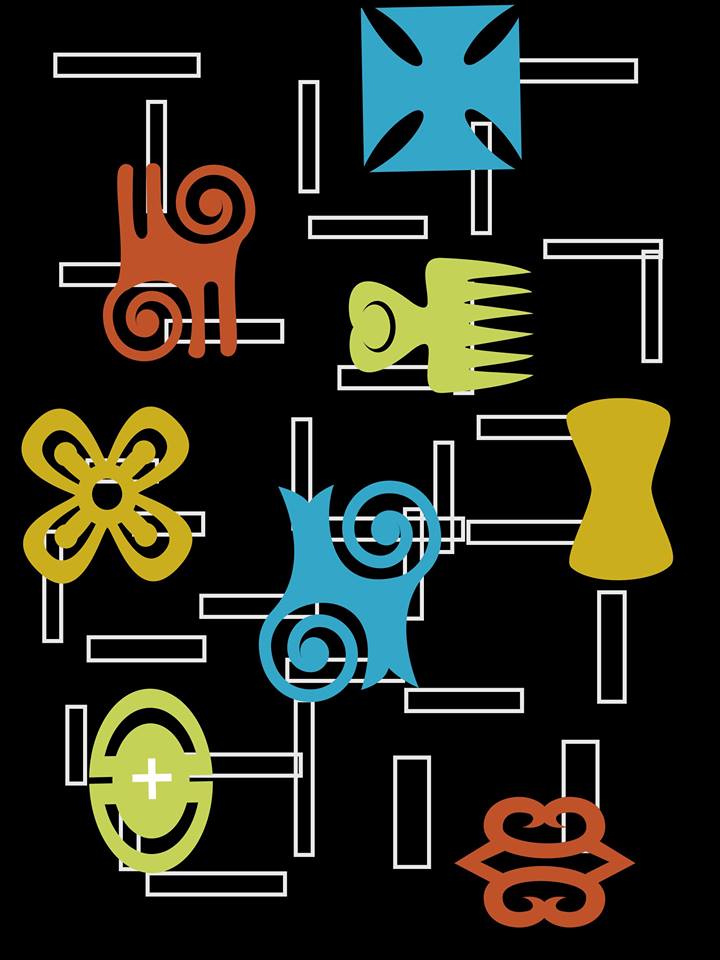

Textile designs have been the most animated form of visual expression in West Africa and have inspired many of the philosophies that underpin prestige and status in the region. The fabrics represent one of the many creative manifestations of cultural identity that have shaped communities occupying its diverse landscape. Cultural, religious and ritual meanings are conveyed by colour preferences, materials, embellishments and design. These textile design traditions provide a rich source of ideas for contemporary designers due to their form, colour and appeal. (Picton & Mack1989; Gumpert 2008; Ross 1998)

Creative Common Model

Copyright laws, intellectual property laws, patents and other legal regimes that protect works of creative persons have not been very practical in West Africa. Discourse in the area is also very limited so Boateng (2009) makes a compelling argument regarding the unsuitability of intellectual property law in West Africa, based on principles of individual authorship, for regulating “traditional” artistic practices that combine collective and individual authorship. She proposed “the Commons” as an alternative model for future research. I am expanding on Boateng’s proposition by recommending that, a model similar to that of the Creative Common1 could be used to make available West African cultural elements that could be used to advance culture. The elements could be placed under one of the following areas: Attribution, Share Alike, Non-Commercial and No Derivative Works. ‘Attribution’ is an instant where people are allowed to copy, distribute, display and or perform indigenous works and derivative works based upon them but in the right context and they give credit to the owners. ‘Share Alike’ is where others are allowed to distribute derivative works only under a license identical to the license that governs owners work. ‘Non-Commercial’ by implication is that others can be allowed to copy, distribute, display and perform cultural works and derivative works based upon it but for non-commercial purposes only. ‘No Derivative Works’ will allow others to copy, distribute, display and perform only verbatim copies of the work, not derivative works based upon it. In all the above instances, where any of the pieces are used for commercial gains, appropriate royalties must be paid and this must be agreed upon before commencement of the project in question. All these could be achieved through a development of support systems that will steward legal and technical infrastructure that minimise the litigations of appropriation and foster sharing, creativity and innovation.

My Narrative

One-way designers could convey a deeper appreciation for ‘indigenous people’ is by offering adequate historical or cultural context of their designs when they reference aspects of the respective culture. To some extent, there is a difference between using a design that is ‘ethnic’ or ‘indigenous’ and able to be used by anyone in the society as opposed to a design that has been developed by an individual and the rights to that design are passed down through the family. To mitigate such ambiguities, I am proposing that indigenous design sources are congregated into three schemes. First, there are ‘design sources’ that are traditional and could be used by everybody. Second, there are ‘design sources’ that are traditional and sacred and could not be copied, reproduced or used in any commercial design endeavour. And third, there are some ‘design sources’ that must be utilised in the right context and with permission. I surmise that, these are critical singularities that could be interrogated further and distilled through the creative common model.

Indigenous textiles production in West Africa should be seen as an industry rather than the wanton mystification that has lost its significance in the modern day. Of course, this should be done with judicious modification of copyright/intellectual property laws, development of workable policies that will protect cultural privacy and make cultural elements profitable moral resources for the common good of the region.

References

Boateng B. (2011). First Peoples: New Directions Indigenous: Copyright Thing Doesn’t Work Here: Adinkra and Kente Cloth and Intellectual Property in Ghana. USA: University of Minnesota Press.

Buchloh, B. (2009). Parody and Appropriation in Francis Picabia, Pop and Sigmar Polke. In: Evans, D. Appropriation. London: Whitechapel Gallery Ltd.

Gumpert, L. (2008). The Poetics of Cloth: African Textiles/Recent Art. New York University, USA: Grey Art Gallery.

Jennings, H. (2011). New African Fashion. London: Prestel Publishing Limited.

Picton, J. & Mack, J. (1989). African Textiles. London: British Museum Press.

Ross, D. H. (1998). Wrapped in Pride – Ghanaian Kente and African American Identity. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Culture and History.

Sanders, J. (2006). Adaptation and Appropriation. London; New York: Routledge.

Young, J. (2010). Cultural Appropriation and the Art. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.