Georgina Williams recently completed her PhD at Winchester School of Art. Here she offers an account of the main research themes and issues.

Propaganda conceived for distribution via a medium such as the pictorial poster creates a body of artwork that can be productively examined from both aesthetic and political perspectives. When this artwork is primarily restricted to conflict propaganda from the second decade of the twentieth century, the temporal and contextual considerations assist in focussing the poster’s role as a functional object, not only within a propaganda campaign but also within the wider visual ecology of an era. These early years of the twentieth century – encompassing as they do the conflict of World War I – witnessed the emergence of the pictorial poster as a useful tool for the state to employ in the distribution of propagandist messaging. Allied with this is how propaganda as a concept was beginning to be considered in the context that we now understand, and both these considerations contribute to why this particular period of history is ripe for a productive analysis of this genre of artwork.

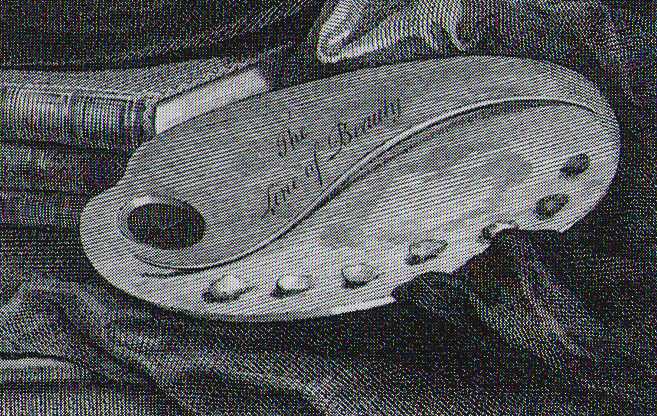

For the pictorial poster to operate as an effective means of propaganda distribution, however, the propagandist requires compositional elements that incorporate constructs considered to be capable of attracting the individual within the mass. If a particular construct is isolated and subsequently utilised in the artwork’s composition, its manifestation demonstrates the potential for its use as a mechanism by which the imagery can be unpacked. The concept of a propagandist promotion of an alternate reality worth striving for as a challenge to a current real – and the prospective movement from one to the other – can be figuratively as well as literally conveyed via an apposite construct’s employment as a pictorial trope. Taking these factors into consideration, therefore, the visual construct deemed to represent “movement” – and not only movement, but movement at its most beautiful, thereby forming a focus for the attraction of the viewer – is the serpentine curve that in 1745 William Hogarth scribed on a paint palette and titled ‘THE LINE OF BEAUTY’ (Hogarth, 1997 p6).

![William Hogarth - 'The Line of Beauty' 1745 [Detail]](http://blog.soton.ac.uk/wsapgr/files/2014/10/William-Hogarth-The-Line-of-Beauty-1745-Detail-300x300.jpg)

References

Hogarth, W. (1997) The Analysis of Beauty edited by Paulson, R. London: Yale University Press.

Ostrow, S. (2005) ‘Rehearsing Revolution and Life: The Embodiment of Benjamin’s Artwork Essay at the End of the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ in Benjamin, A. (Ed.) Walter Benjamin and Art London: Continuum 226-247.