KeepIt course module 3, London, 2 March 2010

Tools this module: Significant properties, PREMIS, Open Provenance Model (OPM)

Tags Find out more about: this module KeepIt course 3, the full KeepIt course

Presentations and tutorial exercises course 3 (source files)

This post was updated on 9 April 2010.

This post was updated on 9 April 2010.

In this module we really engaged with issues right at the core of preservation – developing an understanding of the real properties, functions, behaviours, structures, content and contexts which together provide a thorough understanding of a digital object. It is critical to have this understanding and clarity before we can be confident that we are working to preserve what truly is important about an “object”.

The module focussed on:

- Preservation workflow and format risks

- Significant properties

- Preservation metadata and provenance

This was designed to act as a primer for the following KeepIt course 4, which put this into practice using a preservation planning tool and repository applications.

1 Preservation workflow and format risks

Steve Hitchcock, KeepIt project, University of Southampton

We started our day with a short, informal and enjoyable game for sharing significant data and characteristics amongst small groups. Different groups were given simple numeric data, or four playing cards, and asked to transmit the data around the group using a given frequency of transcription. Sometimes the data was preserved (numbers or value of playing cards), sometimes the format (suit and/or colour) and sequence, sometimes both; and, as we discovered, sometimes data is lost or errors are introduced, and sometimes these can be corrected. This gave us a useful way to capture our attention for significant properties and the actions involved in preserving data.

First, some important background terms necessary to understand the concept of significant properties were introduced.

Open Archival Information System (OAIS) reference model:

Data object interpreted via Representation Information yields Information Object

National Archives of Australia (NAA) Performance model:

Source interpreted via Process yields Performance

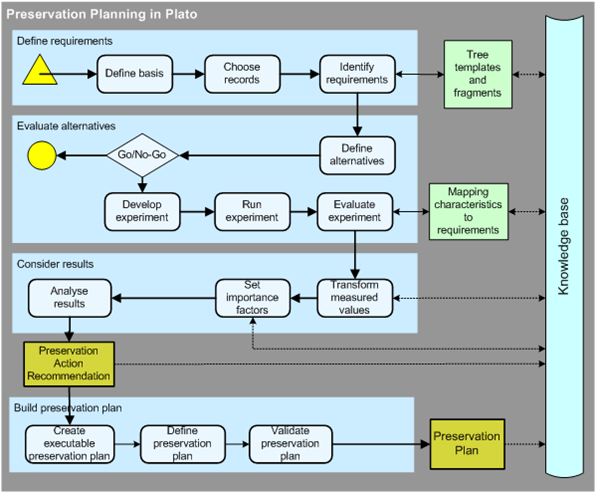

OAIS, as a reference model, provides a way to compare digital preservation systems. This provides us with a mechanism to establish trust between different approaches. It also provides a model that can be aligned with repository processes, such as deposit, content management and access. From an OAIS and content management perspective this can be divided further into preservation-related processes, and among these we find three to describe our preservation workflow for file format management (Table 1).

|

Check

|

Analyse

|

Action

|

| Format – version, verification (tools available: JHOVE, DROID) |

Preservation planning –Significant properties, provenance, technical characteristics, risk factors, (PLATO, PRONOM, Inform) |

Migration, emulation, storage selection |

Table 1. Preservation workflow for file format management

We were given a practical exercise to make a comparison between one format over another, using the PRONOM inherent properties of file formats, and decide which performs better. Groups were given a free choice of which two formats to compare, and each group chose a different comparison. No prior knowledge of the properties was assumed, other than the simple descriptions provided, or they were assumed to be self-descriptive. Two properties were excluded as these are less easy to evaluate without some prior knowledge.

|

PRONOM Inherent Property

|

Word/PDF

|

TIFF/JPEG

|

PDF/XML

|

| 1000 Ubiquity |

PDF

|

JPEG

|

PDF

|

| 1001 Support |

PDF

|

=

|

XML

|

| 1002 Disclosure |

|

|

|

| 1003 Document |

|

|

|

| 1004 Stability |

=

|

TIFF

|

XML

|

| 1005 Ease of identification |

= (or marg.PDF)

|

=

|

=

|

| 1006 Ease of validation |

PDF (internal mechanisms)

|

=

|

XML

|

| 1007 Lossiness |

=

|

TIFF

|

XML

|

| 1008 IP |

=

|

=

|

XML

|

| 1009 Complexity |

Word

|

TIFF

|

XML

|

Table 2. Comparing popular formats with reference to file format properties

As can be seen from Table 2, in each case a clear format winner was identified based on the analysis provided.

We were then asked to consider why we might choose NOT to use the format that performed better for these criteria:

• PDF/Word – Why not PDF? PDF is essentially a conversion format, not a source authoring format.

• TIFF/JPEG – Why not TIFF? JPEG is compressed, would take up less space in storage. This factor may be crucial. Archival quality copy or a derivative?

• XML/PDF – Why not XML? Many repository resources are deposited in PDF. Do people understand what they need to do with XML?

Some thoughts about formats [1, 2]:

• Free vs open source vs open standard?

• MS Office – XML – open standard (Word doc can be saved as XML)

• Open Office – free – XML – open standard

• PDF – page representation

• XML – generic web format, computational

We recognised that it is crucial to work with content creators for repositories – authors, typically, cannot be expected to check to see if they are required to provide a converted copy of a resource [3].

Steve Hitchcock summarised by observing that the issue is essentially that of risk assessment – if we had identified a risk in our personal lives, we would wish to have some way to moderate or to manage the risk – by means of an insurance policy, for instance…..or smoke detectors, alarm systems etc. For repository content there may be very specific risks which we need to undertake detailed analysis and provide specific solutions.

References:

1 Repositories Support Project briefing document on Preservation & Storage Formats for Repositories(May 2008) http://www.rsp.ac.uk/pubs/briefingpapers-docs/technical-preservformats.pdf

2 Rosenthal, D., dshr’s blog, accessed 24 March 2010, various posts on file formats, e.g. Are format specifications important for preservation? (January 4, 2009), Format Obsolescence: the Prostate Cancer of Preservation (May 7, 2007), Format Obsolescence: Scenarios (April 29, 2007) http://blog.dshr.org/

3 Ashby, S., Summary of responses to IR questionnaire. JISC-Repositories, 18 February 2010 [online]. Available from: JISC-REPOSITORIES@JISCMAIL.AC.UK [Accessed 24 March 2010] http://bit.ly/8Zqdjl

2 Introduction to Significant Properties

Stephen Grace and Gareth Knight from Kings College London.

http://www.significantproperties.org.uk

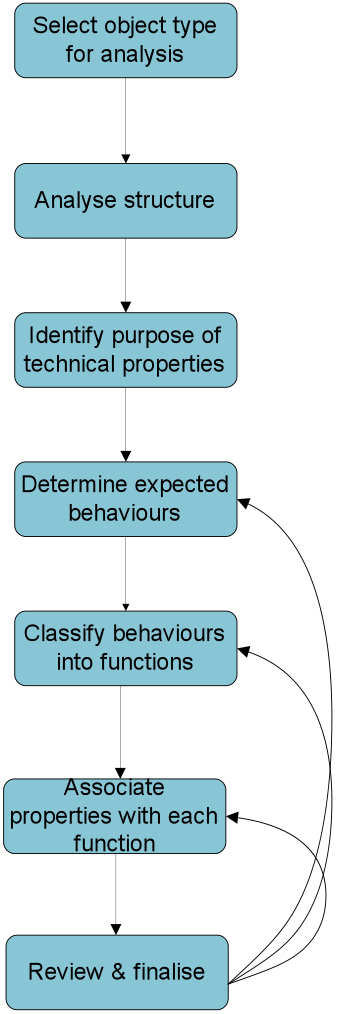

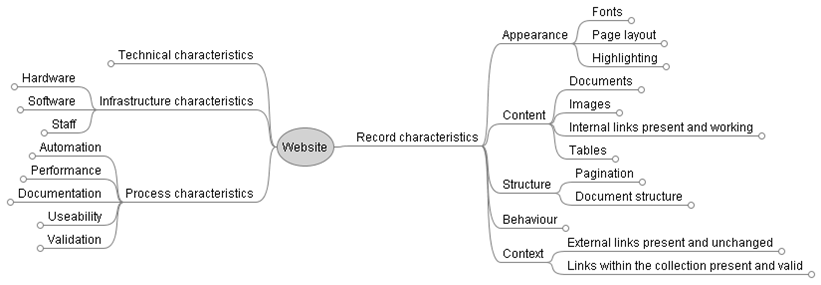

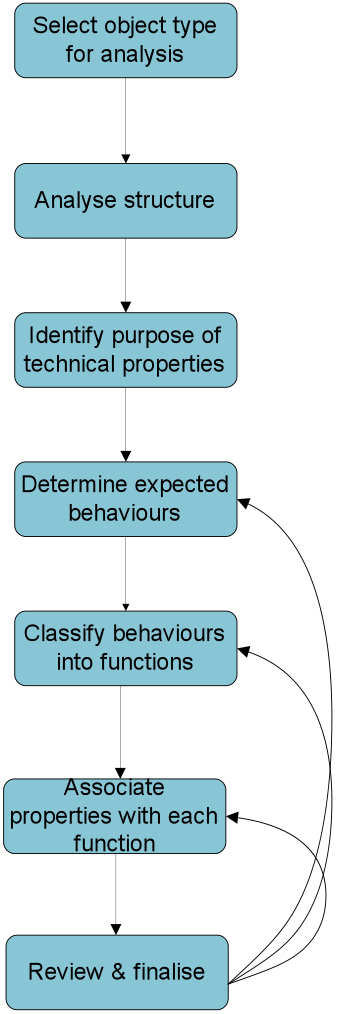

Stephen Grace started off this detailed section of the day with an introduction to the understanding and definition of Significant Properties and their relevance to work of perservation of digital resources. The InSPECT Project: “…adapted the Function-Behaviour-Structure (FBS) framework, a framework developed by John Gero to assist engineers and designers with the process of creating and re-engineering systems.”

In essence, the InSPECT framework suggests that the purposes of a digital object are determined by uses required by specific stakeholders. These purposes determine functionality and in turn, the properties that are needed over a period of time. By concentrating on these aspects, the suggestion is that an institution may develop a speedier, simpler and cheaper strategy for preserving resources over time.

In essence, the InSPECT framework suggests that the purposes of a digital object are determined by uses required by specific stakeholders. These purposes determine functionality and in turn, the properties that are needed over a period of time. By concentrating on these aspects, the suggestion is that an institution may develop a speedier, simpler and cheaper strategy for preserving resources over time.

In InSPECT, FBS – Function – Structure – Behaviour, becomes CCRSB:

- Content – conveys information (human or machine readable)

- Context – information from the broader environment in which the objects exist

- Rendering – how content of an object appears or is re-created

- Structure – components of the object and how they inter-relate

- Behaviour – intrinsic functional properties of, or within, an object

Four distinct stages for identifying the Significant Properties of objects were identified:

- Documentation of technical properties

- Description of specific intellectual entities

- Determination of priorities for preservation

- Measurement of the success of the transformation process

As in other KeepIt training modules, we undertook practical exercises to enable a clearer grasp of the issues we were beginning to address with respect to Significant Properties. In the first of these, focussing on Object Analysis, we undertook analysis of an email. We explored the Content (structure and technical properties); Context (sender, recipient, bcc, cc etc.); Rendering (issues for re-creating an email); Structure (links with other emails in a thread, attachments etc.) and Behaviour (content interactions e.g.embedded hyperlinks).

This exercise was detailed and enabled us to reflect on the inter-connectedness of the properties of an object, the behaviours it might support and the relationship of such behaviours to functions – all of these elements being core to the preservation motivation for maintaining the authenticity, integrity and viability of any resources.

As a complement to the first exercise, we then proceeded to the second exercise which focused on the stakeholders for an email (sender, recipient and custodian) where the perspective was that of a research student interested in understanding research lifecycles by using real life examples. By understanding the stakeholder relationships to an object, we can derive functions for an object as well. Logically, it would then be possible to re-develop any object, with different functions and in support of different behaviours. The concept of Significant Properties then can be “fluid”, supporting a pragmatic approach; although, equally there may be “must have” features which it is imperative to identify.

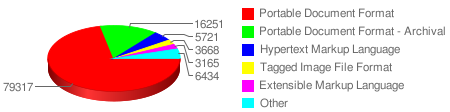

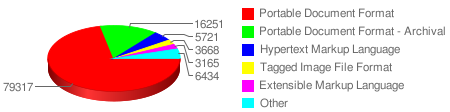

In the next section of the day, we explored the software tools which are available for file format identification and analysis:

Digital Record Object Identification – (DROID) is a software tool developed by The National Archives to perform automated batch identification of file formats. It allows files and folders to be selected from a file system for identification. After the identification process had been run, the results can be output in XML, CSV or printer-friendly formats.

The InSPECT project has used a variety of tools to establish significant properties of various types of file e.g. Aperture, REadPST and XENA for understanding emails.

JSTOR/Harvard Object Validation Environment – (JHOVE) – provides functions to perform format-specific identification, validation, and characterization of digital objects (latest version is JHOVE2).

JHOVE can address the following:

1. Identification

a. “I have an object; what format is it?”

2. Validation

a. “I have an object that purports to be format F; is it?”

b. “I have an object of format F; does it meet profile P of F?”

c. “I have an object of format F and external metadata about F in schema S; are they consistent?”

3. Characterization

a. “I have an object of format F; what are its salient properties (given in schema S)?”

Extensible Characterisation Language – (XCL) – Every file format specification uses a different vocabulary for the properties of each file and stores these properties in its own structures in the byte stream. The Planets team is developing ways to describe these file formats to enable comparisons of the information contained within files in different formats. This is done with two formal languages, called the Extensible Characterisation Definition Language (XCDL) and the Extensible Characterisation Extraction Language (XCEL), which describe formats and the information contained within individual files.

In exploring some practical file type analysis using some of these tools, we noted that although, in principle, the development of these analysis tools is useful there are problems: e.g. they only provide limited format support; they require variable access methods; have inconsistent reporting; may use different metrics; and even suggest metric variations between them. The practical useability of these tools will rest crucially on the capability of specific repository platforms to integrate them into the range of services they offer. No repository manager, administrator or editor will wish to encumber themselves with additional overheads relating to multiple interfaces, metrics and the resolution of internal inconsistencies.

3 Preservation Metadata and Provenance

In the penultimate section of the day’s work, Steve Hitchcock led a presentation and short practical on the means of describing and recording changes to content over time. Preservation metadata “supports activities intended to ensure the long-term usability of a digital resource.”

Steve’s optimistic message here was: “You are probably doing more preservation than you think.”

Repositories are already taking actions that affect preservation and contribute towards preservation results. Migration and emulation strategies require metadata about the original file formats and the hardware and software environments which support them.

The Library of Congress hosts PREMIS (Preservation Metadata Implementation Strategies) – when people refer to PREMIS, they are usually referring to the data dictionary of preservation metadata http://www.loc.gov/standards/premis.

The Dictionary describes and defines over 100 semantic units (i.e. items of metadata)

PREMIS documents four types of entity:

- Objects – things the repository stores

- Events – things that happen to the objects

- Agents – people or organizations or software that act on objects

- Rights – expression of rights applying to objects

(Note: Significant Properties are only a small part of PREMIS, currently.)

PREMIS data may come from: repository software; content creator; repository administrators; repository policy (describing what info needs to be recorded); preservation tools (e.g. format ID may be generated and validated by tools); preservation services.

It is possible to use PREMIS as a reference model and a starting point and add to it to suit the requirements of an individual repository. Some PREMIS fields will already be present in repository metadata. In the future, it is likely that developments for PREMIS will work with the Significant Properties model developed by the PLANETS Project.

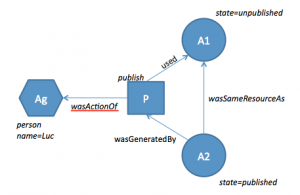

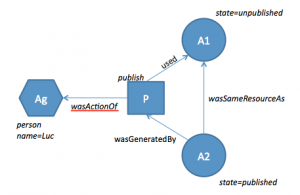

Finally, our day concluded with Steve Hitchcock’s brief introduction to Provenance, linking closely to the work led by Luc Moreau on developing the Open Provenance Model (OPM). The provenance of a piece of data is the process that led to the piece of data – provenance describes and records the results of processes on objects over time. The aspiration for OPM (in development) is to support a digital representation for “stuff”, whether produced by computer systems or humans.

KeepIt course module 3 was a rich and packed session. It is clear, however, that for practical purposes there really needs to be some substantial work undertaken to integrate resources as well as applications to support content creators as well as repository managers in developing policies and practises for preservation. In KeepIt we need to work to support this integration.

Recent Comments