KeepIt course module 4, Southampton, 18-19 March 2010

Tools this module: EPrints, Plato

Tags Find out more about: this module KeepIt course 4, the full KeepIt course

Presentation referred to in this blog entry Preservation planning using Plato (Slideshare)

Presentations and tutorial exercises course 4 (source files)

So far, in the KeepIt training course we have been introduced to a series of tools that will help us, the repository managers, to prepare our repositories for the long term preservation of their content. These tools have covered aspects of organisational preparedness through strategy and policy (DAF and AIDA); issues around costing (KRDS and LIFE3); and description for preservation using significant properties, metadata and provenance (InSPECT and PREMIS).

In session 4 of the course we finally reached what I believe will be the core tools for repository managers – the Eprints preservation apps (including the storage controller) and the PLANETS tool, Plato. Although I’ll be concentrating on Plato in this post, it will really be the interaction between Eprints and Plato that I hope will allow me to preserve my repository content in a manageable and cost-effective way.

About Plato

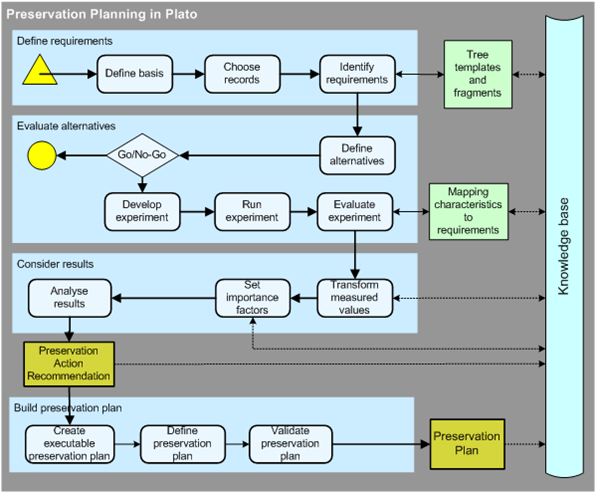

First released in November 2007, Plato is described as a ‘preservation planning tool’ . It defines a consistent workflow which will lead to a complete preservation plan for a given set of objects:

“A preservation plan defines a series of preservation actions to be taken by a responsible institution due to an identified risk for a given set of digital objects or records (called collection).

The Preservation Plan takes into account the preservation policies, legal obligations, organisational and technical constraints, user requirements and preservation goals and describes the preservation context, the evaluated preservation strategies and the resulting decision for one strategy, including the reasoning for the decision. It also specifies a series of steps or actions (called preservation action plan) along with responsibilities and rules and conditions for execution on the collection. Provided that the actions and their deployment as well as the technical environment allow it, this action plan is an executable workflow definition.”

http://www.ifs.tuwien.ac.at/dp/plato/intro_documentation.html

Our tutors, Hannes Kulovits and Andreas Rauber of the Vienna University of Technology, took us through the various steps in the development of the preservation plan:

Starting with defining requirements, we considered the context of the preservation plan, including what triggered the preservation planning activity. Institutional constraints, legal obligations and the target community all play a part here. If the organization has a preservation mandate or mission statement then that is relevant at this stage too.

For the purposes of the plan, a selection of records need to be considered. The sample should be representative of the features and characteristics of all objects in the collection. Stratification by file type, size, content and time of creation may be appropriate. We were advised to use the DROID and JHOVE tools to identify file formats.

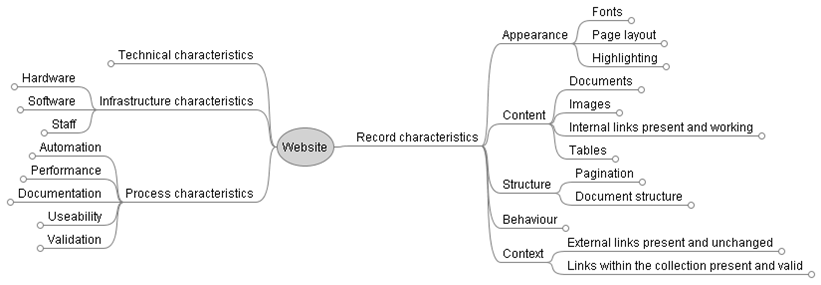

To identify requirements it was stressed that we would need input from a wide range of colleagues, including content producers, managers, lawyers, technical specialists and others. The purpose of this step is to define all the relevant goals and characteristics of the plan. Four groups of characteristics were suggested: object characteristics, record characteristics, process characteristics and costs. In the practical exercise for this section we used the Freemind mind-mapping tool to describe the linkages between these characteristics and then we used the in-built facility to import the requirements into the Plato tree editor.

Rather than try to describe the full set of requirements, KeepIt course members each tackled a small part of the requirements tree. Even this was sufficient to cause much discussion among our small groups – especially when it came to assigning measurable units to each ‘leaf’ of the tree. In our group we decided that a set of templates showing the ‘normal’ requirements for a range of object types would be a useful addition to the Plato tool. This would give new Plato users a benchmark against which they could consider the specific requirements of their own institution.

Moving on to the evaluation of alternatives, we thought about the suitability and possibility of different preservation strategies and tools for each object in the sample. Migration and emulation are the most obvious contenders. Examples of alternative strategies might be conversion from DOC to RTF or PDF format, or migration from one version of PDF to another. For each alternative it is necessary to define which tool to use, which functions and parameters of the tool, and what resources would be required. This leads on to the Go/No-Go decision for each alternative: whether to continue the preservation procedure or not.

If continuing, then the next tasks are to develop, run and evaluate standardized experiments on the object. The PLANETS testbed was used for this. The value of the experimental approach is that objects can be moved through a consistent set of steps, producing results that are comparable and repeatable. By conducting experiments, different tools can be evaluated and the outputs assessed according to the requirements previously defined. The most appropriate tool may then be chosen for the eventual transformation of the objects in the collection.

In our group exercise we experimented with using different tools to convert image files from .gif to other image formats. We examined criteria such as the availability and ease of use of the tool, the change in file size and image quality and the time taken to perform the transformation. In real life, each of these criteria would be weighted according to its relative importance to the organization and these weights would be allowed for in the analysis of the results.

Having followed the Plato process, it is easy to have confidence in the resulting preservation plan. The methodology is both thorough and sound, and decisions based on this will be fully accountable.

Using Plato in the repository

Like most tools designed to support digital preservation, the Plato tool was not originally intended for use in repositories. Repositories are often complex digital collections containing files in a multitude of formats, with metadata that may be inconsistent and/or incomplete. So the Plato concept of ‘collection’ is potentially very helpful. It enables the repository manager to address the preservation needs of a subset of repository content, a ‘collection’ defined by a set of common characteristics. For each collection a preservation plan can be created and then implemented as needed.

Recognising the point of need is where the new tools in Eprints come in. Eprints is now able to perform an analysis of file formats and identify those that are at risk of no longer being accessible or editable. This information can be used to trigger action according to the preservation plan created in Plato. The transformed objects can then be re-imported back into Eprints, now at a much lower risk of loss.

Of course this does not obviate the need for vigilance by the repository manager. In the discussion which followed the presentations on Eprints and Plato, Dave Tarrant reminded us to be proactive about preservation – to identify potential risks and make repository users aware of these. For some repository content there may be no migration solution (e.g. for scientific datasets); the repository manager may have to make the risk explicit (e.g by documenting it) and allow others to develop a preservation solution.

Nor do the tools provide all the answers. Plato and the new Eprints tools are both in a relatively early stage of development. As Andreas said, showing that a prototype works is quite different from widespread deployment. These solutions need to be turned into a preservation infrastructure, supported by robust digital preservation standards.

One Response

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.

Continuing the Discussion