Lisa Temple-Cox’s doctoral research centres around a practice of drawing, focused upon issues of the body after death. In this post she reports upon a ‘dissection drawing event’ she attended organised by BIOMAB (Biological and Medical Art in Belgium) and in collaboration with ARS International and the University of Antwerp’s Faculty of Medicine. This annual event brings together independent artists, medical and anatomical arts students and their tutors, and surgical students from Antwerp University.

The opportunity to draw from life, as it were, in the dissection theatre is now extremely rare. Gone are the days when the study of anatomy in arts included working from bodies that were not only unclothed, but exposed beneath the skin. Jacques Gamelin’s series of expressive anatomical drawings of écorchés, published in his 1779 Nouveau Receuil d’Ostéologie et de Myologie, were subtitled ‘dessiné après nature’: as opposed, I assume, from working from casts or sculptures – the notable écorché of an executed smuggler in the pose of ‘the dying Gaul’ (nicknamed ‘Smugglerius ‘ by generations of 18-19C art students at the Royal Acadamy) comes to mind.

The event took place over two days. The first day was at the veterinary school of the University of Ghent, which offered the opportunity, via dissection of a number of donated animals, to learn about the differences between animal and human anatomy We saw, among other organs, a dog’s five-lobed liver – that organ which Galen used, erroneously, to describe a human liver, basing his work on human anatomy through animal dissections. (His work dominated Western medicine for over a thousand years until challenged by that ‘greatest single contributor to the medical sciences’, Andreas Vesalius, of whom more later).

The morning being taken up by the dog dissection (fig1) – donated, after it’s natural demise, by its owner who is a member of staff at the school – in the afternoon students were given the chance to work either from fresh specimens or to explore the on-site museum. While it was difficult to choose between the lab and the museum, I was very interested in the displays of animal teratology that the latter contained. It was in the museum that I came across this cephalothoracopagus calf skeleton (fig2): a fascinating comparative object against which to consider a similar (human) teratological specimen I’d drawn in the Mutter Museum on a previous research trip.

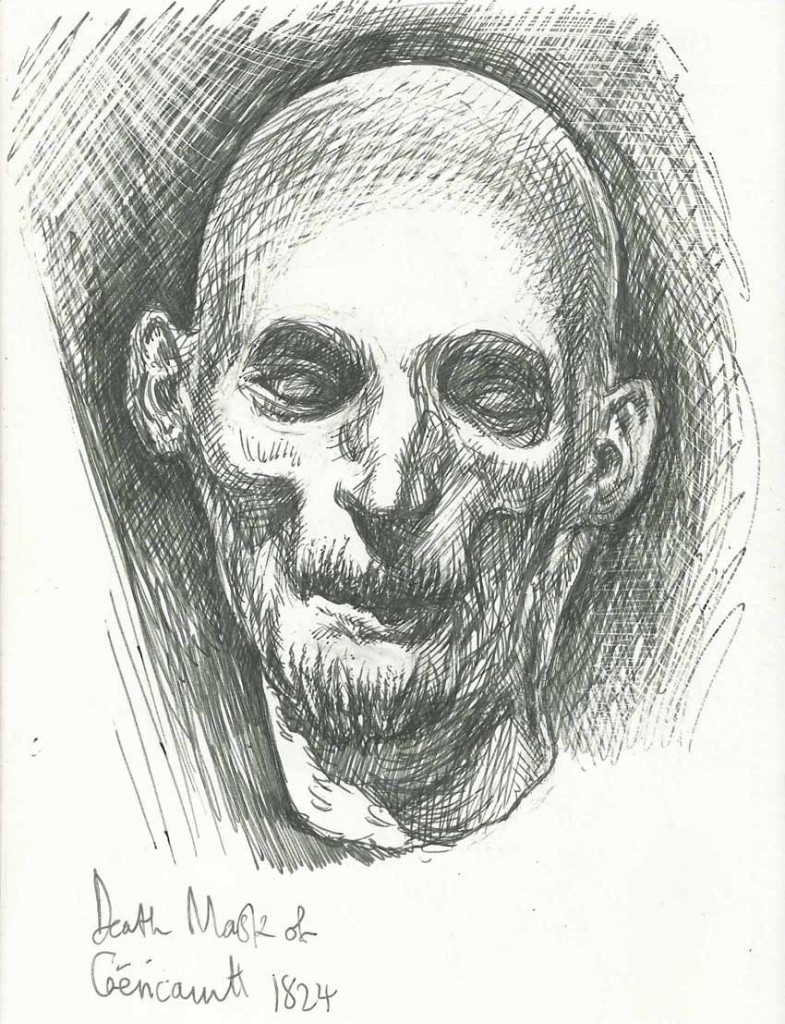

An additional and unexpected benefit of this trip was that it coincided with an incredible exhibition at the Museum voor Shone Kunsten Gent: “Gericault: Images of Life and Death”. The exhibition began with a copy of ‘The Raft of the Medusa’ painted around 1860 by Pierre-Désiré Guillemet and Étienne-Antoine-Eugène Ronjat – the original not being permitted to leave the Louvre – and included a huge number of Gericault’s sketches and paintings, as well as supporting images by his contemporaries and influences, historical political information, sculptures, paintings, and contemporary artworks. I was especially excited to see – in the flesh, so to speak – his preparatory studies for the Raft, including the oil sketches popularly known as ‘the morgue paintings’: a happy coincidence given the reason for my visit, and that they form part of my visual research. The exhibition further included a number of death masks, moulages, anatomical atlases and plates – including some of Gamelin’s écorché drawings – and a life-sized, full colour print from Jacques-Fabien D’Agoty’s ‘Myology Complete’ showing the muscles and nerves. Most striking, however, was Gericault’s own death mask. Starkly lit and gaunt in the extreme, the skull could be discerned, even through the medium of plaster, under the taut and fragile skin of his face: echoing his own studies of severed heads, here was the artist, anatomised. It produced, in me, neither horror nor disgust – a philosophical distinction much discussed in his day – but, like the anatomical plates, and the dissection drawing event that was the primary purpose of my visit, inspired a kind of fascination that bypassed the grotesqueness of suffering and entered the realm of the Pieta. (fig 3)

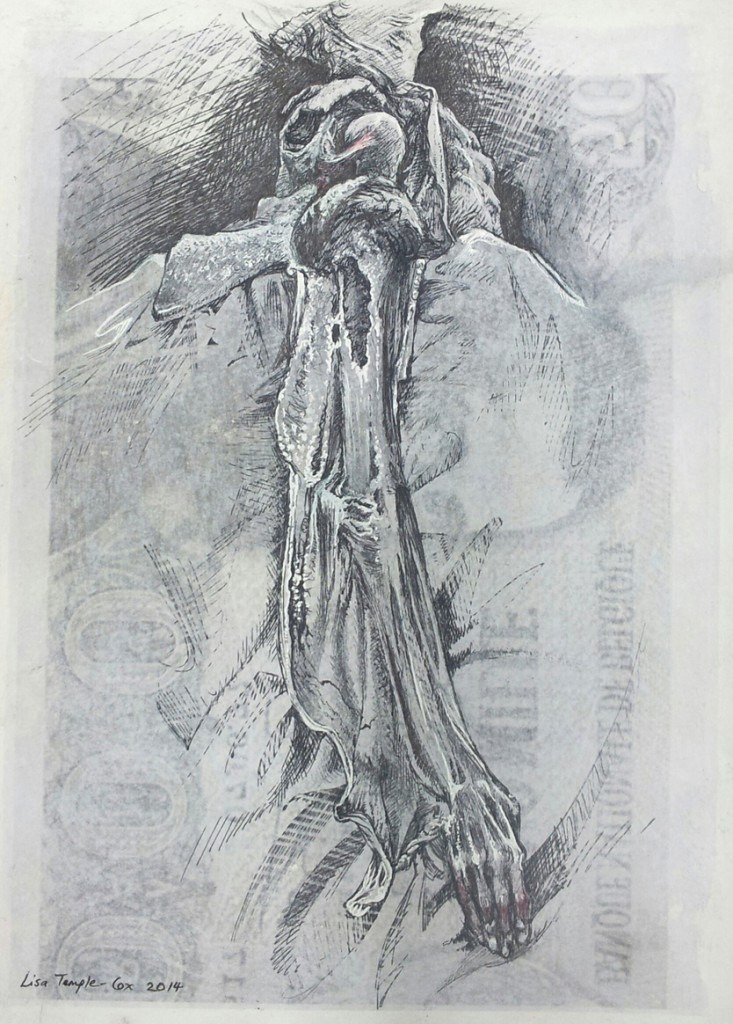

The second drawing day took place in the dissection lab at the University of Antwerp, where a range of body parts – both preserved in formaldehyde, and fresh – were laid out for students to work from. During this session the surgeon, Francis Van Glabbeek, continued a dissection on the left arm of the cadaver, (fig 4) an elderly woman who had died naturally and generously donated her remains to the school, while one of his surgical students dissected the throat. Throughout these processes they described what they were doing and explained the anatomy, pausing at regular intervals to allow for students to make notes and sketches. During our visit some footage was filmed as part of an upcoming documentary charting the life of Vesalius, who was born in Brussels in 1514, and whose anatomical atlas – De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543) – changed the study of human anatomy in ways that continue to be felt. In conversation with Van Glabeek – whose interest in the history of western medicine includes a personal collection of some very rare tomes, the Fabrica included – I was informed that Vesalius’s treatise known as the Epistola Docens was, in his opinion, the first PhD as we know them today. He explained that it was not, as was usual at the time, a doctorate gained by the repeating of knowledge already known, but a document which sets out a problem and methodically shows the steps taken in order to solve it and arrive at a conclusion – a pertinent and timely reminder of the scholarship and enquiry that underpinned the work of all the participants of this event.

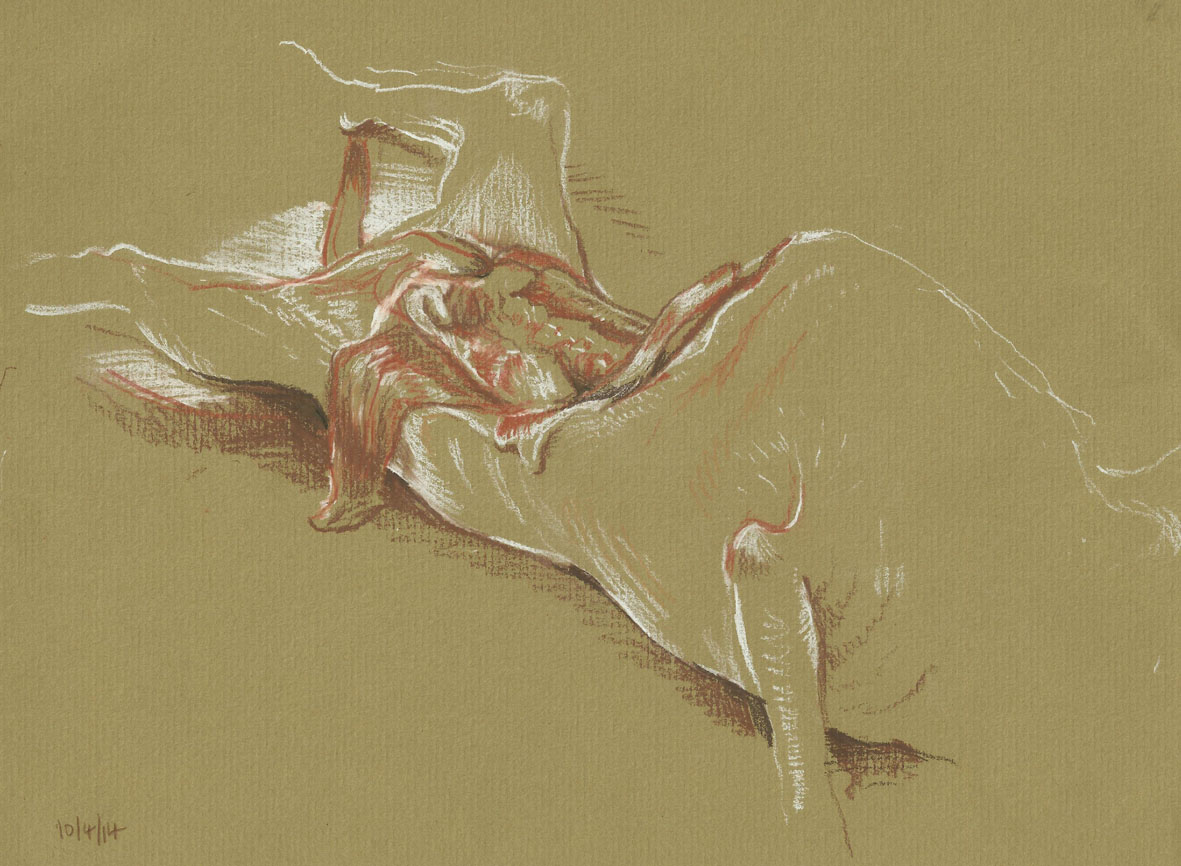

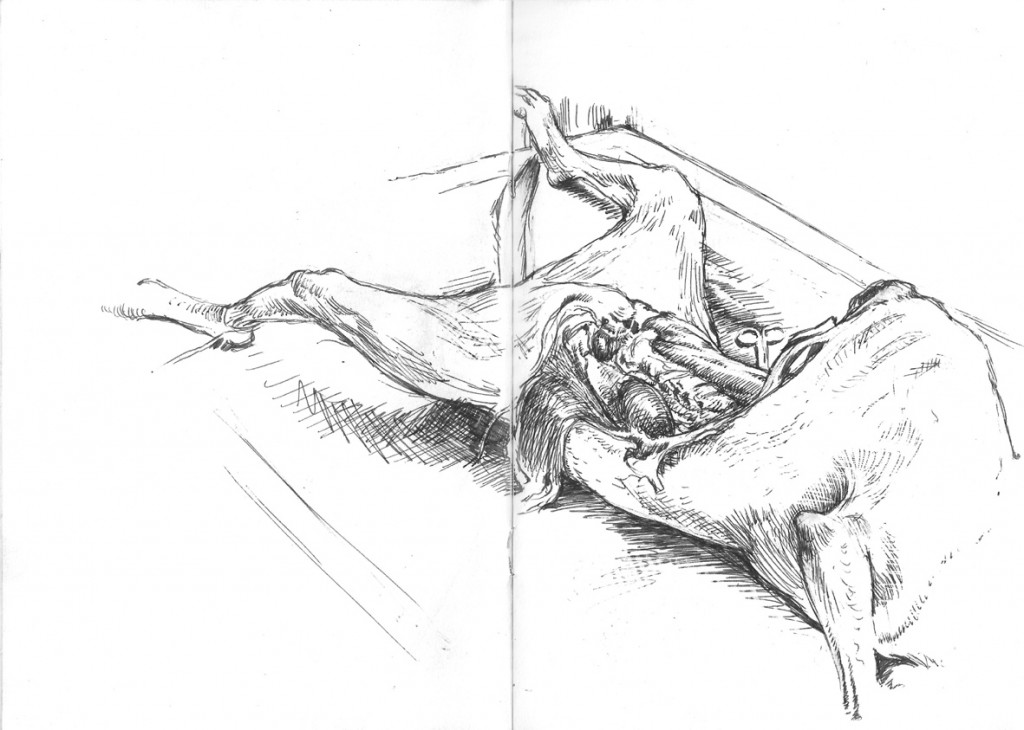

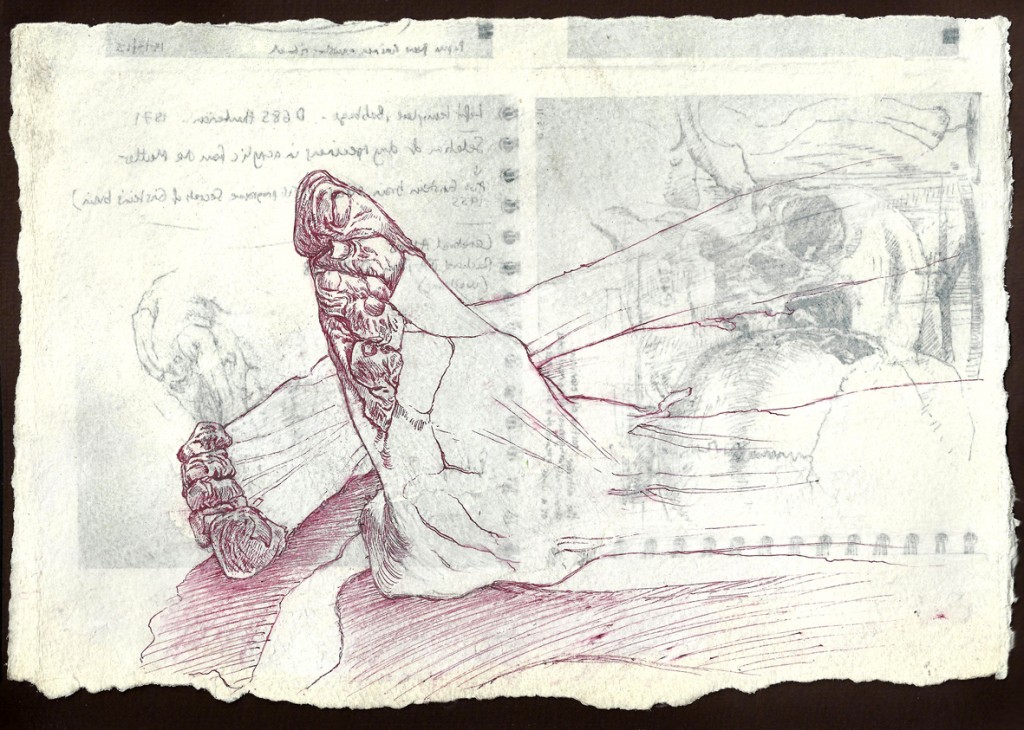

Aside from conversations over the course of these two days, many of which have opened up new or additional lines of enquiry, I found the event useful on several levels, creative and philosophical. In this opportunity to see beneath the skin – enter the hidden world of the body – there is something both beautiful and disturbing. It is a transgressive act, the cutting and incising: simultaneously revealing and destroying. I was moved and fascinated by the carefully exposed surfaces of the bones of the arm, with the wing of skin and sinew folding away from it – like an elegant shawl, or Isadora Duncan’s scarves with their movement arrested mid-dance. (fig 5) I was as drawn to the stripped arm this year as I was to the careful cutting of the hand last year (A process that I felt compelled to watch and draw even as I experienced an unpleasant sympathetic sensation in the tendons of my own hands.) This year additionally provided a pair of legs: already part-anatomised, the only skin left on the spindly limbs were the toes, strangely wrinkled and folded flat against each other. I drew these too, but thankfully my own toes did not respond. (fig 6)

For more information:

Illustrations from the works of Andreas Vesalius by J. B. deC. M. Saunders and Charles D. O’Malley. Dover Publications, New York 1973

Gericault: Images of Life and Death Exhibition Catalogue, edited by Gregor Wedekind and Max Hollein. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2014

http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/theodore-gericault/

http://morbidanatomy.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/theodore-gericaults-morgue-based.html