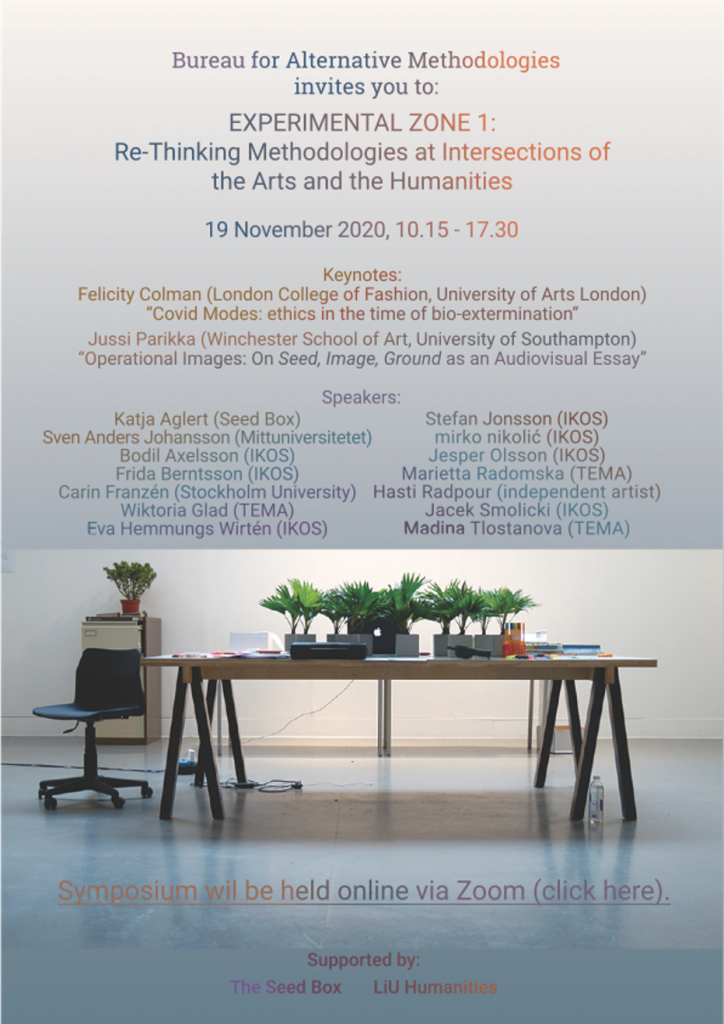

EXPERIMENTAL ZONE 1: Re-thinking Methodologies at Intersections of the Arts and the Humanities is the first of a series of planned events organised by a group of scholars and artists at Linköping University (Linköping, Sweden) under the tentative and temporary heading: Bureau for Alternative Methodologies (BAM). The following report on the event was kindly provided by Ana Čavić, a current WSA PhD candidate.

The one-day symposium, which took place on Zoom on Thursday 19 November 2020, was not recorded. So, here is my admittedly subjective take on what was a very stimulating event exploring “alternative methodologies” from all sorts of angles. I am reporting on the event to encourage you to attend future BAM events, not only because the topic is relevant to many of us but also because this project is committed to re-thinking methodology. In order to make sense of it for those of you who were not in attendance—and for myself—I have written my impressions down and attempted to put them into some sort of logical order, highlighting some of the main themes. I hope you will find my report informative and an interesting read.

In summary, the event was a kind of “think tank” about what might be defined as “alternative methodologies” today and what they might look like in the future, specifically in relation to the presence of creative practitioners in different research fields, the idea being that the alternative methodologies (new modes and new methods) creative practitioners bring to the table are a positive contribution to research across fields, even as they challenge accepted definitions of research methodology by presenting alternatives to what has existed before and what exists now.

A recurring theme was the pragmatics of how creative practitioners might operate in or across fields, how they themselves might recognise the “new” methodological operations at work in their creative practice when they do emerge and how they might use them to forge new paths in their discipline and across disciplines. The event explored decidedly approaches to research with an emphasis on collaboration and co-creation and a commitment to continue to reconfigure and redefine what is possible in the realm of creative practice and ‘practice as research’ through a recognition of the validity of not only “methods in action”, but also the “works in progress” that such practices might entail. was also a sensitivity and subtlety to the discussion, for example, there was talk of how to begin to describe a type of creative research that “teases out the methodology”, rather than “hammering it out”. Essentially: an emphasis on process and on methodology emerging out of process. Something, I think, a lot of us can relate to.

Jussi Parika (Professor in Technological Culture & Aesthetics at Winchester School of Art) was one of two keynote speakers; he screened an interesting collaboratively-made as part of his presentation. The video essay—as an alternative mode of production and presentation of academic writing was a recurrent theme; several were presented on the day.

Lecture performances also, which speaker Katja Aglert (artist and artistic leader/co-director of ) defined as “a hybrid of an academic lecture and performance art”. For example, she used her as ‘scores’ for lecture performances. She also proposed the notion of the “rehearsal” as a method, by which she meant “repeating, but with a difference”; again, highlighting the processes of research over the product, while at the same time prompting us to consider how to tease out a methodology in cases when the outcomes are not meant to be definitive, but a series of endlessly deferred rehearsals. This made me think of Italo Clavino’s novel If on a winter’s night a traveller, consisting of first chapters only, each written in a different novelistic style. Is it an example of rehearsal as methodology, rather than a pastiche or an homage of the novel? Whatever the case may be, it is this sort of borrowing of methods and modes from one discipline (in this case, the performance discipline, as in “the rehearsal”) and applying them to another discipline (in this, case academic writing) that was identified as a possible “alternative methodology”. Anyway, both were part of a larger discussion about rethinking the production and the presentation modes of academic research. There was also a semi-serious suggestion by one speaker that publishing fiction might be one possible mode of dissemination of academic research in the future.

Dr Sarah Hayden (Associate Professor in Literature and Visual Culture, in the English Department at UoS), was also in attendance. She asked Parikka whether the medium and mode of presentation—the video essay—influenced or informed his mode of writing on that particular occasion, methodologically speaking. The simple answer was ‘yes’, but the more complex answer, which was what everyone was grappling with, had to do with a tentative suggestion that materiality and embodiment were integral to knowledge production (or as speaker Madina Tlostanova alternatively called it “knowledge creation”). Or, in Parikka’s words, that “problems are organised through materials” and that “problems are practiced”. Hence, the aforementioned “methods in action” and the related notion that “thinking is performative”, which was articulated by speaker Sven Anders Johansson (Professor of Literary Studies). His presentation, ‘Body as Knowledge’, foregrounded cognition as a bodied experience. Tlostanova, a Professor of Postcolonial Feminism, spoke of “the body as an instrument of perception” and of “the affective and corporeal aspects of cognition” and how, in order to appreciate embodied “knowledge creation” as research, “one has to set aside existing, dominant knowledge schemes”, echoing Johansson when he said that, generally, there is a “need for new methods in research”.

Jesper Olsson (Associate Professor of Literature, Media History and Information Cultures), spoke of “knowledge as a process and experience… rather than a product”, again emphasising process as well as highlighting another prominent theme: “the experiential, as an interface”. Of course my mind went straight to Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay ‘The Storyteller’ in which he argues for a type of knowledge that is enacted (again, embodied), through storytelling: an ancient experiential mode of sharing of knowledge (even “wisdom”, according to Benjamin), as opposed to sharing mere information. Aesthetics, defined as understanding through sensory perception, also came up in relation to the experiential. Related to that was the notion that artistic enquiry was capable of creating experiences that could put concepts “into more immediate relational effect”, as Tlostanova phrased it.

On the subject of storytelling, Aglert introduced the notion of “more than human storytelling” as means of accessing “more than human perspectives”, literally encompassing everything other than human—the alien. Embracing the alien came up more generally as a strategy, with Olsson suggesting that we might import the poetic strategy of “making strange” from the literary field into other fields in order to gain a new perspective on the research object.

The second keynote speaker, Helen Palmer (Senior Researcher at the Vienna University of Technology, TU Wien), also touched on “making strange” as a methodology. She practices, in her words, “defamiliarisation as a methodology” as a means of “shifting the perception of a thing”. For example, in her writing practice she explores philosophical concepts in a playful way, through “intra-sensory entanglements”, as a way of trying to understand difficult concepts. On the day, this resulted in a part-fictional, part-factual lecture performance in which concepts were “explored through the ficteme: a speculative unit that mobilises material objects or concepts through setting them to work on a fictional stage.”

“Which methods do we need to understand these practices?”

Whether working with new research objects or old research objects newly perceived, how do we deal with the alien, the defamiliarised, the alternative? Along these lines, speaker Stefan Jonsson (Professor of Ethnic Studies) asked what was for me the key question of the day: “Which methods do we need to understand these practices?” This is a question that I pose to myself every time I come across objects of study in my research—for example, a painting used during storytelling performances that cannot be evaluated using traditional (Western) methods of analysis. This is because it is not a painting as it is conventionally understood. Instead it is a storytelling prop, or a memory aid, or an “operational image” used in a system of performance; it just happens to be painted. The “operational image” was a term that came up often, meaning an image that is not necessarily intended to function as an image to be viewed and evaluated in the conventional manner, but one that serves an enabling function in an operation. Parikka is the person to talk to about this, if you are interested in “operational images”.

Escaping the hierarchy of language was also, including through what Tlostanova called “polysemic approaches”, in her case, “to escape censorship”. Making use of the ‘hybrid’ and adopting new writing strategies in combination with other presentation modes and media not reducible to writing came up as a possible alternative methodology, toward an expanded academic writing that is more relational, engaged and attentive to the reader. A key question was posed: “How does an author conceptualise a reader when writing?” It was a question that hung in the air and turned into proposals for how an author might engage the reader when it comes to academic writing, including: make the writing more enjoyable, pleasurable even; use a combination of text and image and try to put them into relation, into systems of relation; and negotiate the levels of accessibility in the writing, taking into consideration what might exclude or alienate a reader and what might enlighten a reader.

Finally, I would like to share an insight that took me by surprise. One of the speakers, Professor Eva Hemmungs Wirtén, an intellectual property researcher, pointed out that even patents preserve some element of the invention’s . She explained that patents are designed in such a way as to not say everything. How then do we make sense of something that doesn’t manifest entirely, something in which secrecy is a constitutive element? This led me to question whether secrecy is a constitutive part of research—and whether secrecy and value are connected.

Optimistically, the symposium concluded with the claim that methods can reform institutions by functioning as institutional critique and a transformative force, that inter-, trans- and multi-disciplinary creative practices are well placed to offer alternative methodologies that can be deployed across disciplines to generate new strategies of production, dissemination and reception of knowledge in order to engage audiences in more effective and affective ways. Interestingly, Palmer also suggested that “transdisciplinarity is one way of defamiliarising the institution”, by introducing alternative systems and structures that operate across disciplines and bring them into new relations.

For further information and future updates regarding The Seed Box programme and BAM activities please visit The Seed Box (interdisciplinary and international Environmental Humanities research program) based at Linkoping Universitet, Linkoping, Sweden.