Archive for November, 2011

Market Segmentation no comments

In marketing a key concept is market segmentation – deciding how to divide your market into individual segments so you can target your products and services, prices, advertising etc to that segment’s needs and demands.

Marketing can be conducted a different levels of segmentation:

Mass-marketing – no segmentation. This is not necessarily a bad strategy. It spreads costs across the largest possible number of customers and makes for a consistent brand image. It does however tend to lead to competing on price which may lead to low profit margins.

Segmented markets – this would be something like the over 55s – quite broad and usually with a lot of competitors – but nevertheless defining some characteristics of the market e.g. interested in holidays during the school term, not interested in low cost mortgages or nappies!

Niche marketing – quite specific groups within a market segment such as the over 55s gay and lesbian niche (yes there are companies addressing this niche). Often an unexpected group with little or no competition.

Local marketing – marketing to a specific town or even store. A supermarket chain may authorise local managers to stock and promote products specific to their store. Can be effective but have to be wary of costs and diluting brand.

Individual marketing – this has always existed at a local level. If the village shop stocks vegemite because you are the one Australian in the village who buys it – then that is individual marketing. Famously the web has enabled large companies to do mass customisation i.e. mass individual marketing. The paradigm example being Amazon.

How does this relate to my research question? The trend in science communication with the public over recent years has been to move away from science communication – which is a mass market one way process – tell them the truth which we scientists are the authorities on – to public engagement. Learn how the public uses scientific knowledge and how local knowledge can integrate with and enhance scientific knowledge. This implies segmentation – possibly down to the individual marketing level.

Business Economics Week 3 no comments

This week I start by looking at business strategy from the perspective of economics. There are basic economic principles underpinning the determination, choice and evaluation of business strategy.

As mentioned in my post on management studies from a few weeks’ back, right strategies (the ways in which organizations address their fundamental challenges over the medium to long-term) are crucial for businesses to survive and beat the competition. Strategic-minded thinking includes comprehensive consideration and reflection upon a business’ mission statement and its vision. For both economists and management theorists, therefore, the aims of a business determines its strategy. Equally relevant, however, for both disciplines are internal capabilities and industry structure/conditions.

Like management theory, economists adopt Porter’s five forces model of competition (Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, 1980) which set out to identify those factors which are likely to affect an organization’s competitiveness. These five forces are:

• The bargaining power of suppliers

• The bargaining power of buyers

• The threat of potential new entrants

• The threat of substitutes

• The extent of competitive rivalry

I will be returning to these five forces next week in the context of considering, specifically, how they apply to the effects of the Web. In the meantime, it is worth pointing out that the five forces model does have limitations. For example, it is a largely static model whereas conditions change over time requiring strategy to evolve over time. Notably, also, Porter’s model suggests that success is dependent on competition rather than the potential for collaboration and cooperation (such as with those downstream vertically from a supplier).

Value chain analysis is also closely linked to the five forces model (according to the definition of Sloman, Hinde and Garratt, value chain “shows how value is added to a product as it moves through each stage of production from the raw material stage to its purchase by the final consumer”). Analysis of the value chain involves evaluating how each of the various operations within and around an organization contributes to the competitive position of the business). Ultimately it is these value-creating activities, which can be primary or support activities, that shape a firm’s strategic capabilities.

Turning to growth strategy, it is worth making a nod here to vertical integration (this will become more relevant when considering the effects of the Web in facilitating disintermediation of value chains over the next two weeks). There are a variety of reasons why forward or backward vertical integration might lead to cost savings (such as through economies of scope and scale), including: production economies; coordination economies; managerial economies; and financial economies. The major problem with vertical integration as a form of expansion is that the security it gives the business may reduce its ability to respond to changing market demands.

Other points of comparison and dissimilarity between management and economics can start to be drawn. For example, a point of difference is economics’ focus on theories related to short-term/long-term profit maximization. There is much debate among economists about whether profit-maximizing theories of the firm are unrealistic (largely due to a lack of information or lack of motivation). This focus is where costs concepts and graphs (demand curves in particular) come in.

A more practical illustration given by Sloman, Hinde and Garratt in respect of the search for profits is the video games war where there are high costs, but also high rewards, from a long-term perspective. In considering the secret of success in the market, online gaming capability and global connectivity are significant factors. Moreover, connection to the internet has facilitated a move towards the use of consoles as ‘digital entertainment centres’, in which users can download content. These developments are likely to continue as long as broadband internet connectivity improves and remains fairly cheap to use.

Finally, in economics, there are various theories of strategic choice (such as cost leadership, differentiation and focus strategy). These strategies can be combined. For example, Amazon had a clear niche market focus strategy – to sell books at knockdown prices to online customers – and this has become a mass market with the spread of the Web and due to lower costs.

Next week, I want to move the focus firmly onto the impact of the Web on business competition as I move on from broad principles of management/economics to specifics. I will kick off with a consideration of Google’s business model.

Economics of intellectual property no comments

In my last post I talked about how economics is necessary because of the scarcity of goods. What is interesting in looking at the economics of intellectual property is that intellectual goods aren’t scarce in the way that other goods are. So does that mean we don’t actually need economics when it comes to intellectual goods?

In short, the answer is no. Even though intellectual goods aren’t scarce like land or labour, they are made artificially scarce through government policy. This creates a market for them.

To see why intellectual goods aren’t scarce, consider this quote from Benjamin Franklin (17??)

“If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of everyone, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it.

Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.

That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation. Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.”

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Isaac McPherson, 13 August 1813

http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/a1_8_8s12.html

An important difference between intellectual property and non-intellectual property (such as money, houses or land) is that the former tend to be what economists call non-rival while the latter tend to be rival. A rival good cannot be used by one without diminishing the ability of another to use it. My consumption of a pizza prevents you from consuming the same pizza. My use of an idea, a design or technique, on the other hand, does not diminish your ability to use that same idea (so long as in implementing the idea I do not use up the only resources available to implement that idea). We can both use the idea of a pizza to make our own individual pizzas without interfering with each other. Such intellectual goods are non-rival – they can be enjoyed by more than one person at the same time without losing value.

This difference is not absolute, however. Some non-intellectual goods are non-rival. Traditional public goods, such as clean air, are non-rival, but they are certainly not intellectual goods. However, most goods that are traditionally the objects of property rights, (money, houses, land) are rival. Similar qualifications apply to intellectual goods, which can sometimes be rival in certain ways. We might call them non-rival in consumption; your ability to consume an intellectual good is not affected by my consuming the same intellectual good. However, your ability to use the good in other ways may be affected by my use of it. My ability to profit from stockmarket tips (which I would classify as intellectual goods) depends on how many other people are using the same tips. My ability to profit from selling you a book depends on whether or not you have already read it. More generally, the ability to profit from an intellectual good is compromised if others are able to consume it for free. However, with these qualifications in mind, two generalisations can be made. Intellectual goods tend to be non-rival, at least in consumption. In contrast, the kind of non-intellectual goods that are typically the objects of property rights – houses, land, vegetables – are rival.

A popular defence of intellectual property takes the maximisation of innovation as the relevant end. This version is assumed in the economic literature and reflected in the wording of United States law on intellectual property:

“to Promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

Another kind of defence takes the protection of individual creator’s rights as the most important thing an intellectual property regime exists to do. According to this view, people have the right to control the things they create with their mind. This includes preventing others from using their ideas.

Economics: the basics, and a digression no comments

I’ve been reading Samuelson’s Economics, a classic introductory textbook. So far I’ve got a better understanding of what economics is about. The essential definition according to Samuelson is that it is ‘the study of how societies use scarce resources to produce valuable commodities and distribute them among different people’. This includes, but is not limited to, the following questions:

• How the prices of labour, capital and land are set, and how they are used to allocate resources

• How the financial markets behave and how they allocate capital to the rest of the economy

• Distribution of income and how the poor might be helped without reducing growth

• Impact of government activities on growth

• Studying swings in production and unemployment and how policies can encourage growth

• International trade

• Growth in developing countries and how to encourage efficient use of resources

Returning to the above definition, we can see that without scarcity – i.e. if there were always enough goods to satisfy every person’s every desire – there would be no need for economics, because everybody could just take what they want and need without depriving anyone else. The desire for efficiency is also essential to economics; if we didn’t care about satisfying as many needs and desires as possible, then we wouldn’t need economics to tell us how to most efficiently distribute scarce resources. The economy is producing efficiently ‘when it cannot increase the economic welfare of one person without making someone else worse off’.

A QUESTION/ DIGRESSION

As an aside, I disagree with / don’t understand this definition. Imagine an economy where most of the resources are in the hands of one person (call him Bill). Imagine, reasonably, that in such an economy no-one’s economic welfare could be increased without making Bill worse off. According to Samuelson’s definition, then, this society is efficient. But surely, you want a notion of efficiency which allows decreases in welfare of one person so long as they result in proportionally greater increases in the welfare of others. If Bill’s income tax for the year is £1 million, and that revenue allows government spending, which stimulates GDP, perhaps it could make 10,000 people £20 richer – a net gain for society. Wouldn’t this be a more efficient use of resources?

From a Google search, I think the notion of ‘pareto-optimal’ captures my pre-theoretical intuition about efficiency – where a pareto-optimal situation is one in which no individual’s welfare can be improved without making another individual’s welfare proportionally even worse off. Imagine that taxing Bill £1 million makes 9,999 other people £10 richer. But this would not count as pareto-optimal, because Bill would have lost more than the combined gains of others (£1 million vs £99,990). That’s what I had imagined an economist’s notion of efficiency referred to, before reading Samuelson. But perhaps I’m jumping the gun here!

…back on topic:

Microeconomics is the study of individual entities such as markets, firms and households. It considers how individual prices are set, the determination of prices of land, labour and capital, and market efficiency.

Macroeconomics came around in the 1930’s when John Maynard Keynes decided to look at the overall performance of the economy. He analysed what causes unemployment and downturns, investment and consumption, the management of money and interest rates by central banks, and why some economies thrive and others fail. These days the distinction between the two is less important, with microeconomics being applied to studying unemployment and inflation.

Economists observe current economic phenomena as well as historic data and make theoretical predictions and broad generalisations on that basis. They also use econometrics, which is the application of statistical analysis to economic data, allowing them to identify the relationships between different factors.

The kind of economy one has depends on three things:

• What goods should be produced

• How should they be produced

• For whom will they be produced

Factors of production are things that are used to create goods and services, and come in three categories:

• Land (and other natural resources)

• Labour – human time

• Capital – goods which can be used to create new goods

Attitudes: Do I have one? no comments

I have found myself in a rather strange territory this week. Under normal circumstances, I would be very offended or at least somewhat disappointed with myself if someone says I have an attitude. Yet, what does the word “attitude” actually means?

“attitudes are defined at least implicitly as responses that locate ‘objects of thought’ on ‘dimensions of judgement’ ” (McGuire, 1985, p.239)

“an attitude is a general and enduring positive or negative feeling about some person, object or issue” (Petty and Cacipoppo, 1996, p.7)

It is interesting to see from this definition that we all have an attitude toward something. It is normal. Most importantly, having an attitude in an academic sense is not wrong. An attitude can be positive or negative. Even negative attitude is not always wrong. For example, having a negative attitude toward murder is generally socially acceptable. This concept of right and wrong, or social acceptance brings us to another closely related topic: Cognition and Behavioural relationship.

Cognition and Behavioural Relationship

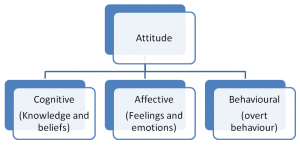

The above model is commonly known as the ABC model for obvious reason. This model was first proposed by Hilgard in 1980 and has since became the fundamental framework for further research. For instance, many have investigated the relationship between behaviour and beliefs. It has been found that behaviours are modified by the peers, identity of self with the peers and perceived social norms.

This is an interesting findings because it backs up the social concept of “peer pressure” and shed light on how these pressures function/ affect an individual. The book then went on to discussion several theories regarding the factors involved, such as: theory of reasoned action, and planned behaviour, social identity, self-categorisation, social norms, group definition and discursive theories.

Time would fail me if I was to detail all of them here. It should be sufficient to say that these theories were used to describe the results obtained from various experiments. It is particularly interesting to see how these theories interact with each other and compliments each other.

Moving On

In view of the time remaining, I will be reading up more on self and identity as I have found this topic rather interesting. That will then be my last post based on text book reading. Further posts will concentrate on multidisciplinary approach and migrate towards final report style thinking/ writing/ blogging.

Economics of Ontologies no comments

Am trying to focus back in on my original assertion about what I was going to study. This was whether there are differences between subjects and their degree of separation from the www, and their primary ontologies. Although I was going to use economics and psychology or perhaps sociology and their attendant ontologies to create a spotlight with which to examine this question, this would still involve looking at the ontologies of a range of other subjects.

Am trying to focus back in on my original assertion about what I was going to study. This was whether there are differences between subjects and their degree of separation from the www, and their primary ontologies. Although I was going to use economics and psychology or perhaps sociology and their attendant ontologies to create a spotlight with which to examine this question, this would still involve looking at the ontologies of a range of other subjects.

I was going to use economics as a focus, as I think it perhaps represents something that might be wrong with how we talk about knowledge in general and reasons for studying, working together, collaborating – ultimately: trust.

A lot of work that we do is tied into research programs that are underwritten by governments as being part of some economic promise. For example, the last Labour government’s education policy was predicated partly on the premise (stemming from research in the 1950s that re-emerged in the 1970s (need to find and cite)) that countries with a more highly educated population tend to do better economically. Thus following Tomlinson’s recommendations, the Diploma system was introduced, only partially, which in fact had the consequence of introducing a system that did the opposite of what he had intended.

This however, being loosely accepted: that the more highly educated a population is, the more wealthy their country, it would seem to follow that it makes sense to make use of emerging technologies to help to educate this population. There is a body of research on this – how technology can be ubiquitous; it can get to the places that teachers can’t, and can help to make learning something that is always ‘on’.

There are actually so many problems with these assertions that it would take a whole other blog post, or perhaps even, essay, or perhaps even, thesis to go into them – but I’m happy to accept that 1) learning is basically a Good Thing and that 2) technology can help to mediate it. I might perhaps then reluctantly accept that it’s possible that if you have a lot of learning, you might end up creating more wealth for your country, however some of the data for this is possibly correlative rather than strongly causal.

But to get back to my original question, it is whether there might be said to be an economics of ontologies? Could we find out whether there are some subjects that lend themselves, via their objects of knowledge to be shared and studied on the web? And that therefore are more accessible and therefore might end up generating more money?

It seems at first glance, that physics might be one of these subjects. Physics research can be large scale and tend to be carried out by large communities who share resources. Is there something about the nature of physics that makes people more likely to collaborate? Are they perhaps true seekers after knowledge who are less motivated by economics / reward than say, chemists? (Apologies to all you pioneering, truth-seeking chemists out there.) Would this then mean that by the very nature of a subject, if it attracts more people who care more about discovery, or truth, then they may well as a result, collaborate more, and could easily use technology in order to do this, but they care less about creating wealth, so that all web-based subjects that can easily or practically use the web to be studied are never going to be worth funding by governments who only care about short-term goals?

This seems on the face of it, rather facile, but it does intersect with another debate about why there still seem to be less girls studying physics, and in general, science subjects. (This debate appears worldwide, but I shall for now confine myself to the UK.) There was recently some speculation about whether the Big Bang Theory was attracting more people to the subject, but this generated some scathing responses from researchers who had determined that take up of physics was in fact governed by early influences.

Future Society IV no comments

This is indeed a time of change, regardless of how we time it. In the last quarter of this fading century, a technological revolution centered around information, has transformed the way we think, we produce, we consume, we trade, we manage, we communicate, we live, we die, we make war, and we make love. Castells, End of Millenium

In Castells‘ last volume of his trilogy, End of Millenium, the author begins with examining the Soviet Union collapse, then discusses the problems faced by Africa and the so called rise of the fourth world as a result of social exclusion. Africa is presented as the exponent for the Fourth World which consists in millions of homeless, incarcerated, prostituted, criminalized, brutalized, stigmatized, sick, and illiterate persons. [..] But, everywhere they are growing in number, and increasing in visibility, as the selective triage of the information capitalism, and the political breakdown of the welfare state, intensify social exclusion. In the current historical context, the rise of the Fourth World is inseparable from the rise of informational, global capitalism. Probably, some good examples in the western world would be the French riots in 2005 or UK riots of this year.

On the other side is the example of Japan where the income inequality is one of the lowest levels in the world. Although the social landscape was transformed by modernizing without Westernizing, Japan’s cultural identity was preserved. We discussed the importance of cultural attibutes of the information society in our previous post about The Power of Identity.

The most fundamental political liberation is for people to free themselves from uncritical adherence to theoretical or ideological schemes, to construct their practice on the basis of their experience, while using whatever information or analysis is available to them, from a variety of sources. [..] The dream of Enlightenment, that reason and science would solve the problems of humankind, is within reach. Yet there is an extraordinary gap between our technological overdevelopment and our social underdevelopment. Our economy, society, and culture are built on interests, values , institutions, and systems of representation that, by and large, limit collective creativity, confiscate the harvest of information technology and deviate our energy into self-destructive confrontation. [..] There is nothing that cannot be changed by conscious, purpseive social action, provided with information, and supported by legitimacy. If people are informed, active, and communicate throughout the world; if business assumes its social responsability; if the media become the messengers, rather than the message; if political actors react agains cynicism, and resoter belief in democracy; if culture is reconstructed from experience; if humankind feels the solidarity of the species thoughout the globe [..] maybe then, we may, at last, be able to live and let live, love and be loved.

We explored Castells views, the marxist leading analyst of the Information Age and the Network Society. In the following posts we will look into a more scientific book called Globalization, Uncertainty and Youth in Society by Hans-Peter Blossfeld, Erik Klijzing, Melinda Mills and Karin Kurz, in order to identify some key problems of our current society and find solutions to them.

Soxciology for Dummies (2) no comments

What sociologists do

1) Empirical Research: using data collected by the various methods we described before sociologists use statistical analysis to draw conclusions about social class, gender inequality etc.

2) Theorists: these sociologists try to develop an understanding and context for the empirical research. To theorise qualitative methods of research are employed and the social theorists paints a picture which explains why the world is the way it is.

3) Critics: this type of sociologist criticise common sense views of the world and carefully dissect social norms which are taken for granted.

4) Educators: they provide students, governments, corporations with information and advice about human interaction, in particular these types of sociologists are found in the media and they try to drive change.

There are several other roles which a sociologist might take and they often assume different combinations of the four roles described above.

Limitations of Sociology

Sociology is the study of human interaction and society, but human interactions and society are part of a changing evolving world. Furthermore a sociologist studies a moving target, any finding as part of some empirical research or a theory may only be relevant for a limited time.

Also, however hard they try; sociologists cannot look on the world objectively. Part of the study of the social is the study of you, thus it is hard to part with the preconceptions about society which we are born with. For example, on a very basic level, it is unlikely for a Chinese and an American sociologist to share a similar theoretical approach.

Another limitation is that social knowledge or theory is fed back into society and then will affect that society. For example, evidence that crime rates are soaring makes the population more aware of crime so they report more crimes; a recursive process.

06 – Museology no comments

Museum Studies

The museums by themselves have different processes and meanings for the population and institutions. Through these classifications of museums, we can provide a more accurate linkage in between the object of study (or exhibited) and the audience.

Cultural Theory

Through contemporary cultural theory we can incorporate all sort of art practices into the everyday life. This will create our culture. So culture is becoming something less separatist in which art or culture itself no longer belongs to the educated or rich classes. The cultural theory is now being implemented more and more within museums, specially in social history and contemporary collections (Macdondald, 2011). Contemporary cultural theory seeks to utilize culture from a pluralistic perspective.

We inhabit a culture in the sense that we share a certain amount of knowledge and understanding about our environment with others.

We have evolved into a society that shares what Stuart Hall (1997: 18) in Macdonald (2011:18) defines “cultural maps” which makes us question or make judgements the value, status and legitimacy of products or cultural practices.

Within museums we are trying to materialize values and trying to give meaning to objects. For this reason museums within cultural theory are public spaces in which their values and the culture creation is always under debate.

Main theoretical apporach

In order to give meaning to something, we depend on a social construction of a signifying system that creates a shared understanding. The semiotic research of Ferdinand de Saussure, indicates that signifiers and signifieds relate arbitrarily. This means that perhaps the meaning or classification (curation) system to an object could be completely different from the perspective of a different culture.

When an artifact is being curated, this is attached or linked to an interpretation system that could be attached to a single cultural ‘string’. Taking the post-structuralist approach, we can provide a structure of interpretation that adapts to the cultural needs of the artifact or the audience. The attempt to materialize culture and present how an object can change through time, tends to fit to the vision of the post-structuralist thinking.

For this project this could be the way in which post-structuralism becomes the main way of presenting an object of study. A multi curated object presented from different cultural backgrounds and within different cultural audiences. Although the object can be presented with several meanings, “poststructuralist theory does not automatically imply that the material world ceases to exist” (Macdonald, 2011:21), but it will be understood from different perspectives or meanings.

V&A Mark Lane Archway (Gallery 49)

The Object

Before photography, multimedia and all the new technologies, the object by itself was the way to present the culture or places which it came from. For this reason I think that the object presented should contain enough information to communicate or represent the specific qualities of a culture. When the object is unique it will be a challenge to transmit the embedded information to a replica that could be presented somewhere else. The use of modern manufacture technology and prototype making can assist with this process. But it will be the correct adaptation of the object and its environment what will be able to make the correct communication to the audience possible.

Bibliography

MACDONALD, S. 2011. A companion to museum studies, Malden, MA ; Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell.

PEARCE, S. 2001. Interpreting Objects and Collections, Andover, Routledge, 2001.

Business Economics Week 2 no comments

This week I looked at the workings of competitive markets: first in basics, before turning more specifically to my research question around how the Web has changed competition between businesses from an economic viewpoint. I continue to refer to the Sloman, Hinde and Garratt book, ‘Economics for Business’ (5th ed).

As outlined in my posts on management studies from previous weeks, firms are greatly affected by market environments (particularly when it comes to pricing strategies). The more competitive the market, the greater the domination of the market over firms (e.g. resulting in ‘price takers’ nearer the model of the ‘perfectly competitive’ market when price is entirely outside a firm’s control, rather than ‘price setters’ nearer the model of the monopolistic, ‘imperfect’ market).

Although price is often at the heart of competitive strategy, the significance of non-price factors of competition should also not be underestimated. By differentiating one firm’s products from another’s, such as through design and marketing/advertising, firms seek to influence demand. Of course, the most dramatic growth in advertising expenditure over the last decade or so is on the internet (which increased from virtually nothing in 1998 to nearly 20% of all UK total advertising expenditure in 2008 based on data in the Advertising Strategic Yearbook 2009).

The better a firm’s knowledge of a market, the better it will be able to plan its output to meet demand. In particular, knowledge related to the size and shape of current and future demand choices by consumers is critical to the investment decisions that businesses make (Philip Collins, OFT Chairman, Speech 2009). Such predictions include the strength of demand for a firm’s products followed by responsiveness to any changes in consumer tastes (particularly when the economic environment is uncertain). Collecting data on consumer behavior is therefore highly valued by businesses, assuming it can be analyzed properly so it can be used to estimate price elasticity and forecast market trends and changes in demand. Price elasticity as a concept is the measure of the responsiveness of quantity demanded to a change in price. Methods for measurement include market observations, market surveys and market experiments.

Conversely, consumers face a similar problem when they have imperfect information about, in particular complex, products/services. In finding ways for consumers to trust information provided by sellers, establishing a reputation and third parties helping firms to signal high quality can assist. For example, Sloman, Hinde and Garratt refer to the online auction site eBay providing a feedback system for buyers and sellers so they can register their happiness or otherwise with sales.

The supply side of the market is just as important as the demand side. Businesses can increase their profitability by increasing their revenue or by reducing their costs of production. Both these concepts are subject to economic theorizing to discover the particular output at which profits are maximized. The answer in any one case is heavily dependent on the amount of competition in the market which is measured, in turn, by concentration levels.

E-commerce is a force at work undermining concentration (dominance by large consumers) and bringing more competition to markets. Its effects include:

• Bringing larger numbers of new, small firms to the market (‘business to consumer’/B2C and ‘business to business’/B2B e-commerce models), which can take advantage of lower start-up and marketing costs.

• Opening up competition to global products and prices, resulting in firms’ demand curves becoming more price elastic particularly when transport costs are low.

• Adding to consumer knowledge, through greater price transparency (e.g. through price comparison websites) and online shopping agents giving greater information on product availability and quality.

• Encouraging innovation, which improves product quality and range.

On the other hand, e-commerce disadvantages still include – for example – issues around delivery (such as timing) and payment security. Furthermore, larger producers may still be able to undercut small firms based on low cost savings from economies of scale.

Sloman, Hinde and Garratt provide an interesting case study of the challenges to Microsoft by the antitrust authorities in the EU and the US – something which I am very familiar with as a former competition lawyer. This example is illustrative of the balancing exercise required when assessing the virtues of allowing very large firms to be unfettered in terms of their potential exclusionary practices, versus allowing smaller firms a more even playing field to challenge such large firms which could dampen the latter’s investment in innovation over the long-term.

Of course, new internet-only firms (such as Facebook and Google) have very different business models from that of Microsoft, including the provision of numerous free products as part of a desire to create large networks of users and heavy dependence on tailored advertising revenues.

Next week, I will look at business strategy this time from an economic (rather than management) perspective.