Archive for the ‘Sociology’ Category

Research questions and chosen disciplines no comments

Hello! Sorry for the tardiness of my first post.

My research questions are (currently):

How can we make an effective mathematical model of the web? How can we make an effective mathematical model of social networking sites? How can we best use these models to “understand” the web and how people use the web?

These questions are rather vague and hopefully they will be refined over the next four years.

In order to make such a mathematical model we must decide what basic properties the model should have. This argument appears circular, needing to know properties of the web in order to make a model which will inform us of properties of the web! However, we are really investigating the (sometimes hidden) effects of these known properties and what they mean for the web.

For example we might want to model Facebook. We could associate Facebook with a graph G by assigning people to nodes and then draw an arc between two people if they are friends. Since it has been shown that two people with mutual friends are more likely to be friends themselves than two people with no mutual friends, one property of G is that it has an abundance of triangles. This means that if node A is joined to node C and node B is joined to node C then it is likely that node A is joined to node B.

In practice drawing G would be virtually impossible because Facebook changes constantly as new friendships are created and destroyed and people join and leave Facebook we make a model graph M (a more convenient graph which we generate and can control). In order to be a good model M must have an abundance of triangles.

Note that the seemingly abstract mathematical property, an abundance of triangles, comes about for a sociological reason. What other properties should the model graph have? To find this out it will be vital to understand how people use the web, so I have chosen to study sociology/philosophy as my first discipline.

Such mathematical models could be used to find the most efficient route from node to node (in the Facebook example from one person to another and be useful at looking at the spreading of ideas). These models could also be used to measure the resilience of a network from attack, (i.e. how will a network cope if we knock out some nodes?) hence I have chosen criminology as my second discipline.

The Pit and the Pendulum of extended and over-elaborate metaphor no comments

Mors ubi dira fuit vita salusque patent.

So, to expand the first blog post a little: what I think is nagging at me is this sense of a range of ‘objects,’ of pieces of ‘knowledge-meat’, or ‘currency’, that are consumed or traded within their own disciplines. Sometimes these objects of knowledge have the same names in other subjects, but they mean different things. And across disciplines the means of making them edible, civilized, tradable can be hugely different. Traditionally these bits of ontologies, of data (they are sometimes data) are going to somehow be examined, discussed, prodded, perhaps measured: quantified or qualified in some sense. In the past this might have been described on paper. These days, some of us (perhaps not that many, globally) have the web as a means of mediating discovery and knowledge acquisition. There are many things that can be done with knowledge on the web: it can be hidden, it can be spread, it can be created, it can be pushed around. If tiny bits of data somehow fit with the tiny little pieces of the structure of the web, then one might suppose that a sort of true picture emerges. However, again, something that has nagged at me is how so much of our thinking is analogical, or metaphorical. So that true pictures are actually very hard to locate using reductionist mapping – see Wicked Problems, for example.

What I think might be part of one of the questions I want to pursue, is to do with how the web might change the analogies that are implicit or embedded within disciplines. Sometimes the process of collaboration can bring out these assumptions. Sometimes, collaboration is hugely impeded by them.

For example, one of our widely used assumptions or analogies that fascinates me, is that which describes electricity. Electricity has long been portrayed as a commodity. Walter Patterson (a physicist by trade) has written at length on this subject, in a book called, ‘Keeping the Lights On.’ The traditional picture of electricity is of something that ‘flows’ like water, and can be cut off, traded, conserved, or wasted. Entire forests have been destroyed in the pursuit of the subject of electricity and our consumption of it. Generations of schoolchildren have suffered sleepless nights, worrying (somewhat misguidedly) about global warming’s fatal pendulum hanging over the Polar Bear every time they put their heating on (along with the location of the calorie – another rather elusive and misleading concept.)

Patterson says, “How many times have you heard or read some energy specialist refer to ‘energy production’ or ‘energy consumption’? These people are supposed to be experts. Surely they ought to know one unbreakable law, the First Law of Thermodynamics, the law of conservation of energy. No one produces energy. No one consumes energy. The amount of energy in the whole universe remains the same.”

He then goes on to describes a host of assumptions that arise incorrectly out of our making electricity a commodity to be traded, the most simple being that arising from the regulators who are allegedly looking for the best deal for the household market – a low unit price does not equal a low bill – the holy grail for the ‘consumers.’ To me, having worked with the UK’s largest energy company and, in particular, with their hard and soft data, it’s clear on a fairly elementary level that describing our relationship with electricity like this is going to cause anxiety for the ‘consumer’. It describes a selfish market. It’s all about measuring how much we use, and not the quality of our relationship with it. Too much = red, not very much = green. It’s almost a little bit childish. Imagine designing an app to somehow map our relationship with energy. It would have reds and greens, wouldn’t it? It would be about ‘a lot’ (scolding) or ‘a little’ (caressing tone of voice- well done.) It would be great to break from this model and look at different ways of being technical about how we are with energy.

Even as I’m doing my preliminary, slightly distracted, coffee-table pre-reading, this strikes a chord with me. A book I picked up a couple of weeks ago, written by Stephen Landsburg is called, ‘The Armchair Economist.’ (In the manner of many inhabitants of armchairs he keeps disappearing just when I want him. I’m also wondering if The Spy in the Coffee Machine can see him from the kitchen, and if so, whether they should talk. Never mind.)

The first chapter of this book starts boldly with, “Most of economics can be measured in four words: ‘People respond to incentives.’ The rest is commentary.” He then goes on to describe, or perhaps, hypothesise, how making cars more safe kills more people, as people drive more safely in more dangerous cars. Landsburg continues by saying that economics begins with the assumption that all human behaviour is rational. I’m presuming that part of the rest of the book is to decry this notion triumphantly. It is very fashionable nowadays (and seems to cause great joy for the evolutionary psychologists) to show how entirely irrational we are; however I can’t help feeling that there is sometimes a confusion in the literature between say a system of perception, or of governance that overcorrects, and the net result that that has for the movement and/or survival of its owner. (I know, feeling something isn’t really academic: it’s another question to explore.)

So, now I have economics and markets intruding a little into my original speculation about how the concepts or metaphors embedded in disciplines might be creating pictures that aren’t entirely correct. It’s certainly the case that while markets have their own language, they also trade in the languages used by the disciplines that come together to create the products or objects on sale. And now, for some of us, the sorts of things that can be traded, over the net for example, are elusive objects, which it might be worth while trying to pin down a little further. I’m worrying that some of this sounds as though I’m just talking semantics. I do intend to explore this further and show how it’s not just trivial misunderstandings, but deep ones that maybe re-cast our notion of the world to some extent.

As far as a methodology goes, my approach to research is often about contingency. Particularly interdisciplinary research. I don’t believe that using a wholly empirical, top-down filtering method is always going to work, as this assumes that there is an explicit pool of knowledge out there to be refined. My very subject matter says that this might not be the case. So, although I intend to use the traditional method, and my next step is to get my text books on economics and psychology/ sociology, and to read and annotate findings from them, I will also read a lot of not-quite academic, coffee-table stuff that gives me a feel for whether I would be happy to say, sit and have lunch with the people who are writing. And, more immediately, I’m suffering from a nagging sense of not having figured out what the correct referencing procedure for blogging is. I’m used to using hyperlinks and checking they’re still live every now and then. Suspect I might need proper references.

I also haven’t yet drawn out my reasons for an interest in psychology, but, quickly, this is because I think that in the pursuit of truth (which should arise somewhere when looking at how subjects are affected by the web), it is is probably going to be interesting to look at what drives people to co-operate and trust each other when working together within specific subject areas that use specific ontologies that might or might not be affected by the emergence of the WWW.

I am now releasing these thoughts into the wild, where they can roam about in a sort of purgatory of waiting for approval.

Self and business in social networks no comments

I was considering the two topics – social networks and consciousness from the perspective of Psychology and Marketing. But as I found later the more appropriate fields would be Sociology and Social Marketing.

After the class on Wednesday, one nice colleague boroughed me the book Social Psychology by Brehm, Kassin, Fein with the suggestion that I could also look into Sociology. As I was reading through this book and thinking about the topics, I came across the The Self-Concept which is just another term for self-consciousness. We can describe self-consciousness by looking at the main methods through it is achieved:

- introspection = looking inward at one’s thoughts and feelings

- perceptions of our own behavior = analyzing your own behaviour you can find out how you react in certain situations

- influences of other people = identifying yourself through comparison with others

- cultural perspectives – depending on the origin of the individual he might be an individualist (its values are independence, autonomy, self-reliance) or a collectivist (its values are interdependence, cooperation and social harmony)

So point 3. states that self-consciousness is influenced by others. In the Royal Society presentation called Understanding social and information networks given by Professor Jon Kleinberg: http://royalsociety.tv/rsPlayer.aspx?presentationid=499 the speaker shows the probability of joining a group based on the number of friends already joined:

The web is now a social phenomenon, it isn’t just a place to access and share information, it is a world of its own where people interact, live and change. This is an unprecedented phenomenon in human history.

And as the world changes, the way of doing business also shifts from the traditional marketing techniques to a more valuable, customized approach. A suitable quote from Socialnomics by Erik Qualman would be the following:

Marketer’s Philosophy Yesterday

- It’s all about the sex and sizzle of the message and brand imagery

- It’s all about the message; good marketers can sell anything

- We know what is right for the customer – we are doing the customer a service because they really don’t know what they want

Marketer’s Philosophy Today

- It’s important to listen and respond to customer needs

- It’s all about the product; it’s necessary to in constant communication with all the other departments

- We never know what is exactly right for the customer; that is why we are constantly asking and making adjustments

The topics that I touched in this post (and will in the next ones) were the self-concept and how it relates to the social-self, new ways of doing marketing taking into account this new type of individual. Until the next post, I will

- have a look into Sociology to understand the driving forces of social networks

- read more from the book Socialnomics because it describes how social media transforms the way we live and do business (this is actually the book subtitle)

- look into more social marketing books to find out the methods of doing business in this brave new world

Strong Programmes in Sociology no comments

I think I might as well add what I am currently reading by David Bloor to some of my thinking on the question of subjects/disciplines and the web. This is because I may be using sociology methods or ontologies as one of my lenses for examining the question (once I settle on the question).

And, more importantly, the reading paves the way for a discussion on the social construction of technology ie. it is in contrast to the technological determinism that seems to abound in the media. (Especially the Daily Mail!) Have just got slightly side-tracked here looking at the Wikipedia entry for social constructivism, or social construction. I’m not sure I entirely agree with what’s said there, especially as I have come to social construction in the past from psychology. (This is going to turn into a giant aside, might need another post to link to here. But in essence the entry seems to be framing social construction in terms of by-products of choice, rather than natural laws, which instantly seems to create one of the countless dichotomies that litter psychology and philosophy. Am not certain that such a dichotomy is necessary. )

So, as a part of our reading around the philosophy of science, we looked at a number of thinkers like Lakatos, Feyerabrand, Kuhn and Popper. We also looked quickly at Bloor. In defining a strong programme in the sociology of knowledge, (sorry, am referring to what he says he’s doing, not the title of the article which is the same), he says that rather than trying to define what knowledge is, independently of how people construct it, ‘knowledge for the sociologist is whatever people take to be knowledge.’ He also, rather magnificently, says that, ‘The cause of the hesitation to bring science within the scope of a thorough-going sociological scrutiny is lack of nerve and will.’ He then acknowledges this to be a psychological explanation, although depending on perspective, I think there can be failures of nerve and will that run through entire societies – in which case the treatment of what must apparently then be epistemological deficits cannot be (or at least, should not be?) purely bounded by psychological explanations. My thinking this also points to, I imagine, the fact that I think he’s correct but should perhaps be less apologetic in his approach. The paragraph that instantly caught my eye was the one that began, ‘how is knowledge transmitted, how stable is it, what processes go into its creation and maintenance, how is it organised and categorised into different disciplines or spheres?’ This, for me, was yet another ‘Oh Wow’ moment, as this description first, really mirrors what I wrote above on how knowledge is treated on the web, and second, is actually very similar to the way we talk about curating or maintaining web-pages. (And once I get more advanced, hopefully, how I might start looking at hypermedia, about which I know very little, but I can now see, after today’s lecture, is something I NEED to know about very urgently.) For Bloor’s sentence on knowledge above, it’s entirely meaningful to add ‘on the web’ to everything he says – instantly casting the web as something that is very strongly to do with knowledge, a cognitive extension.

So, I now have some words from sociology (although alluding to or perhaps also sitting within philosophy of science) that fit quite snugly around my set of questions to be refined.

Bloor sets out four conditions that make for a strong framework, which are: causality, impartiality (surely a little question-begging?) symmetricality, and reflexivity. I don’t necessarily think systems of knowledge have to be reflexive: by definition if not everything is founded in inductive, scientific, detached knowledge, then the things being described or observed don’t really need to bootstrap themselves up via the same cantilevered mechanism. (He does discuss this, as I will.) However, I love the idea of the same types of cause explaining both true and false beliefs. Again, I would hedge my bets about causation since almost everything physics seems to tell us is that our notions of cause and therefore of explanation are local, but I think that a lot of what we see and understand in the world is most elegantly alluded to by what we don’t see, what we misunderstand, the ways in which we are wrong about things, the shadows left by a lack of light and the ways in which our explanations break down.

Identity (Post 5 – More Anthropological Views) no comments

This post will hopefully conclude the final underlying principles and theories of Anthropology, as described in Small Places, Large Issues. These latest concepts have centred on social systems and social structures, with the two being distinguished as:

- Social Systems: Sets of relationships between actors;

- Social Structures: The totality of standardised relationships in a society.

This definition of social systems relates to social networks – the relationships from a particular person, and the scale of these networks has to be considered in contemporary Anthropology as the Internet has meant that non-localised networks are of increasing importance compared to the traditionally studied small-scale societies. Rather than simply focusing on online research to study these networks, however, anthropology stresses an importance of collecting other forms of data: specifically on relationships between online activities, and other, offline, social activities. By doing this, it has been shown that the Internet/Web can surprisingly enhance people’s national and even religious identity, with the example of Trinidadians whose offline and online activities form a single entity – their identity does not seem to be being altered by the Web.

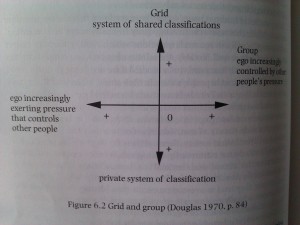

Grid and Group Classification of Societies - from "Small Places, Large Issues: An Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology" Second Edition, by Thomas Hylland Eriksen, page 82.

The above image displays a classification system for societies that focuses on social control. The “Group” axis classifies societies according to their social cohesion, and “Grid” on the shared knowledge in a society. A strong grid, strong group society is explained as a strictly conformist society where an individual’s identity is constructed through the public system of rights and duties. The measures on this grid can help to explain how the identity of individuals in certain societies is shaped through the social control exerted by the social system itself. A typical industrial society could fall in the weak group, weak grid sector (although they can be spread out over the graph), where members are “individualistic and anonymous, and thus others exert little social control over ego” (page 83). A counter argument is that the influence of the state on a society means that they should fall into “Strong group”, so the variation in opinions here is vast and the classifications all seem uncertain and unreliable. It appears to have more value when classifying one particular society, rather than a group such as “industrial society” which is far too vague.

There are differing schools of thought that cover the link between society and individual actors:

- Individualist thought, associated with Max Weber where anthropologists try to find out what makes people do what they do

- Collectivist thought, associated with Marx and Durkhein where anthropologists are more concerned with how society works.

Theories that focus on the actor emerged to critique structural-functionalist models in the 1950s. In these models, the individual was mainly looked over, with focus instead on social institutions. This was criticised, as it was not clear how a society could have needs and aims, and because society can only exist because of interaction – this implies that social norms must be seen as a result of interaction, and not the cause. The author summarises by stating that while structural functionalism seeks to explain cultural variation, it only succeeds in describing interrelationships.

Finally, it is described how Bourdieu examined the relationship between reflexivity or self-consciousness, action and society, resulting in a theory of “culturally conditioned agency”. “Habitus” is the term used by Bourdieu to describe “embodied culture” which enforces limitations on thought when choosing an action, and ensures that “the socially constructed world appears as natural” (page 91). This raises the question of how much of what we do and who we are is just down to habits, conventions and norms imposed on us by the society we are born in to?

As the subject matter of the book is now beginning to move away from the core anthropological theories and on to more specialised areas I will start to focus my reading on specific chapters relating to Identity to build up my knowledge of this area, before moving onto some introductory psychology texts.

Sociological Thinking: Part 2. no comments

This blog is a continuation of my last entry where I discussed classical sociological thinkers. This post continues this theme to explore the ideas of more contemporary sociologists. The main reading for this post was Giddens (2006).

Sociological thinking has developed primarily in the post-WW2 years in order to make sense of an increasingly diverse yet inclusive society. Technological advances in media and transport have led to the emergence of a modern world where geographically distant cultures can interact and share norms with little or no regard for their geographical history and specific community development. Some sociologists, such as Jean Baudrillard, argue that this new world is one dominated by media and icons, where mass consumerism and ‘new media’ fosters a generic and homogenous culture driven by a small number of values and desires. While this is perhaps a slightly bleak view of modern society, these concerns highlight the importance of maintaining cultural identity in a modern world.

There is an argument to say that while we do indeed live in a world where the majority of human inhabitants are governed by the same laws and social norms (for example; neoliberal economic theory and consumerism) we are able, thanks to the advances in technology within our lifetime, to be aware of the existence of cultures and societies outside our own and attempt to foster relationships with one another. Michael Foucalt was a sociologist who specialised in theories of power relationships and the values that sprung out of increasingly connected networks. His work on changing ideas within medicine, from medieval to the mid 20th century, presents a view that societies establish values and ideals after a long process of expert opinion and debate. As networks grow and organise into factions, certain schools of thought emerge that promote different values. Once these schools gain a critical number of adherents, the value becomes a popular social value. It is important to note that these schools of thought begin life as fringe ideas, and expand to become socially accepted as their number of followers grows. To Foucalt, being familiar with a value is no basis for blind acceptance, and no society has a set of values which are unchangeable.

In a world dominated by capitalism and capitalist thinking, many people would be forgiven in assuming that the socialist ideas of Karl Marx no longer hold sway. However many sociologists believe that, while economic liberalism has put paid to Marxist economics, there is a need for a socialist way of thinking in terms of social organisation. Arguments for this way of thinking come primarily from contemporary sociologists Jurgen Habermass, Ulrich Beck, Manuel Castells and Anthony Giddens.

Habermass argues that the modern world and modern communication techniques have now little in common with traditional governmental institutions. Collective decision making and democracy now needs to capitalise on the new forums for discussion that are available, particularly the using of Internet technologies.

Beck identifies a similar theme of the changing nature of the establishment, and argues that the growing trend of ‘globalisation’ within economics and social institutions is promoting what he calls a ‘risk society’, whereby risks to society become globally connected, and the actions of one particular society, in one particular area, have far reaching consequences for all connected. Beck admits that this situation has always been the case, but in modern times the risks have grown to be truly global and potentially devastating. However, Beck sees hope in the emergence of widely coordinated and distributed networks of ‘activists’, people who share the same set of values and work to promote the acceptance of their values in political and social frameworks. Unfortunately these networks also have their dark sides, exampled by global terrorist networks, but these are unlikely to succeed in generating mainstream societal change, whereas issues such as the environment or poverty eradication have a large degree of success when it comes to establishing new social principles.

As a further example of the changing attitudes of Marxist thinkers, we can look to Manuel Castells. Castells has identified, like Habermass and Beck, the emergence of a globally linked societies, but his interest in Marxian economics leads him to identify the increasing role of telecommunications and computer networks as a basis for global capitalist production. This view differs from traditional Marxism which identifies the working class as the basis for societal change, and Castells argues that we are live in a world influenced by technological determinism, where technology is increasingly determining and enforcing the direction of societal progression. This concept is the subject of much contention is sociology, and stems from the “human action vs social structure” argument of classical sociologists.

Finally, Anthony Giddens has developed a school of thought, ‘Social Reflexivity’, which places a great amount of importance on the notion of trust within social organisation. Expanding on the ideas of Beck, Giddens agrees that the world we live in has the potential to operate outside of the limits of our control, but that by constantly being aware of actions and decisions regarding lifestyle choices, societies can exert great influence on the underlying economic, political and cultural principles which are endemic to their existence. Giddens sees the path to overcoming the ‘Risk Society’ as being one of transnational, global cooperation that develops not from inter-governmental relationships, but from the self-awareness and identity recognition of societies, both internally and externally through global communication networks.

What I have learned from my introduction to both classical and contemporary sociological thinkers is that sociology seems to be a discipline that is often in flux. The ideas of classical sociologists maintain core theories which lie at the heart of sociological research, but it is a merit of sociology that sociologists are able to adapt these principles to their own environments and time periods. That is not to say that one can simply make up sociological theories. The analysis of contemporary sociologists appears to show and adherence to principles, or an acknowledgement of past research and theories in their work. For this reason, the study of sociology is one that requires a sound understanding of all genres and theories within the field, relating as they do to all of the various levels and ideologies that exist in our societies.

Comte to Communism, I have no idea Weber any of these are right. A tour of Sociological thought no comments

This week I am going to examine the classical theoretical approaches which have influenced sociological thought for the past two centuries.

The first true sociologist was Auguste Comte. Comte was the first to coin the term sociology, which he introduced after his initial thoughts on social physics contrasted with the thinking of many of his peers. Comte argued that society conforms to invisible laws, and that by following these laws societies becoming functioning bodies. Comte suggested that sociology must follow an agenda of positivism, and be a positive science, that is sociology must use strict research methodology to inform its findings and theoretical models. Comte argued for the use of experimentation, observation and comparative studies on observable behaviour. It was observed that society has evolved from a theological perspective, society focusing on god(s) and religious practices, metaphysical societies, based on natural observations and natural science, observable in early renaissance societies, towards a positive society, based on scientific reasoning. Building on this, Comte suggested that theological religions should be disbanded, and replaced by a religion of humanity, based on a scientific and secular truth, this would fundamentally, in Comte’s view, improve society as “false superstitions” and a belief in gods and daemons were detrimental to society. Although Comte’s vision has not come into being, his theoretical ideas heavily influenced initial sociological thinking.

A follower of Comte was Emile Durkheim, who also argued that sociology should follow an empirical methodology, however suggested that Comte himself had not acted or theorised in an empirical manner. Durkheim argued that the main focus of sociological study should be social facts. Social facts are any and all aspects of social life that affect individuals. Societies are gestalt constructs, which are more than a mere collection of individuals. Social facts act in a coercive nature to impose rules and regulations on individuals and impose order. Individuals’ who fail to follow the rules experience a state which Durkheim labelled as anomie, a sense of aimlessness and disenfranchisement.

Karl Marx signalled a departure from the approach of Comte and Durkheim. Marx argued that economic systems are central to the formation of societies. Marx suggested that capitalism was fundamentally composed of two factors, capital and wage-labour. Capital is a form of wealth such as goods and money, which can be reinvested to create more capital. Wage-labour is the work of individuals who compose of the proletariat, workers who lack insufficient capital to be employers themselves. Marx argued that this inevitably leads to a two tier system and society. Marx argued that this disparity inevitably leads to conflict between the limited number of capitalists and the much larger proletariat, who are forced into an exploitative relationship. Marx suggested that society is conceptualised by a material conception of history, whereby social change is prompted by economic factors, based on this idea, Marx argued that economic change is inevitable, and that as the proletariat outnumber the capitalists, it would be inevitable that capitalism would fail, to be replaced by communal ownership, in a system Marx labelled communism, a society which due to the lack of competition and conflict would be more innovative and productive, in many ways a utopian society. It is worth noting that theologically Marxist communism was not the same as the communism imposed in the U.S.S.R, by Lenin, and his followers, as soviet communism was still a two tier system with an empowered state, not a workers’ paradise. It is in many ways ironic that the web and the internet, with its basis in capitalism, western defence initiatives and ARPANET could (currently) be seen as a purely communist society, where fundamentally everyone is equal.

Disagreeing with Marx, Max Weber suggested that despite economic factors playing an important role in the development of society, ideas and vales play an equally important role. Weber also argued, against the ideas of Comte and Durkheim, that society was formed by the actions of individuals, and does not exist outside these interactions, change emerges not from economic changes but shifts in cultural values. Weber suggests that rather than capitalism and class conflict producing change, a cultural shift towards rationalisation, organising society based on efficiency, has lead to large scale fundamental changes in social structures. Weber does argue however that this movement does lead to a danger of crushing the human spirit in a de-humanisation as workers become little more than robots, completing repetitive activities.

The impact on sociology of the ideas of the founding fathers has be large, with schools of thought and styles of analysis developing around many. The most influential and preeminent school for much of the history of sociology has been functionalism, based on the ideas of Durkheim. Functionalists suggest that society is a set of complex relationships between individuals and groups, and often uses an organic analogy, that is society is a living object, made up of many objects, whereby if one part fails then the whole dies. It clear therefore that the functionalist approach focuses on peace and harmony between groups, drawn together by a morale consensus and agreement on the values that the society should promote. Merton suggests that functionalism can be extended to the individual actions of groups and individuals rather than just looking at large scale societies. Merton distinguishes between the manifest function of an action, and the latent function, manifest functions are the intended or primary function of behaviour, compared to latent function, as unintended or secondary functions, an example of this could be a football fan going to watch their team play, the manifest function of the behaviour is to watch the team, however the individual also gains secondary benefit as being a member of a social gathering and gaining connections to a wider community. Similar examples can be seen looking at online MMORPGs and MMORTS’s, where strong communal ties develop between players in addition to the players playing the games. Merton also suggests that any behaviour may have both functional and dysfunctional attributes associated with it, for example the football fan may gain positive benefit from being in a group, yet the group may engage in anti-social behaviour such as hooliganism. Merton stresses that it is the actions of indivi8duals which create society, rather than society existing as a directing force with a predetermined mandate.

The second main approach is conflict theories, stemming from Marxist views. Conflict theories state that society is made up of many disparate groups, all of which are forced to compete for resources, such as goods and power. Although the main influence on conflict theories being Marxism, others have influenced this school, such as Dahrendorf who argues that as societies are not utopian there is an inevitability to conflict between groups in a perpetual power struggle, based on Darwinian views.

The final main influential school is that of symbolic interactionalism, championed by Mead. Mead argues that society is a collection of individuals and groups that share common meaning between a large scale set of symbols, which form a fundamental point of agreement. This has lead Hochshild to suggest that changing social structures is due to a change in the nature of the symbols and the expansion of the accessibility of such symbols. Included she argues that the exchange of symbols has allowed the growth of an emotional labour market, whereby the symbol of happiness can now be made into a financial asset, to the point that many airlines ask stewardesses to complete smile classes.

As can be seen sociologist have fundamental differences in their approach to answering questions. This gives a wide range of opinions, stimulating further research and diverse range of approaches, to tackling the many diverse issues facing modern society.

The British empire isn’t dead, It’s just gone digital no comments

This week, I went historic.

As part of my sociology reading, it was apparent that societies do not just exist in isolation, but rather are the product of thousands of years of traditions and culture. A central theme suggested by Gidden’s is that society is the product of uncertainty, when individuals work together they increase their chances of success. In response to this, society can be seen as having evolved in distinct epochs, hunter-gatherers, pastoral and agrarian societies, traditional non-industrial, post industrial or modern societies, and post modern information age societies. Not all societies evolve at the same pace, if at all, with external factors influencing their development. According to Kautsky (1999) traditional societies were based on the desire to create an empire, for control of limited resources. Post industrial revolution, there was a mass exodus of labour from the countryside and a migration in to cities which became large population centres, with this migration came a shift in social life, as people became one of many, the majority of relations became impersonal.

In response to the decline of traditional communities, a new community was formed, with the rise of the nation state, individuals felt part of a much larger society, as such rather than being a member of a village they became English, or French, or Spanish. (As an aside historically Italy and Germany became states long after most of Europe, and they remained city states far longer) The rise of the nation states gave far more influence to the relative governments, allowing for the start of national agendas.

The growth of nation states allowed for the expansion of western imperialism, founded primarily on fortune and firepower, nations were far stronger, both in terms of sheer productivity, and technology, such as gunpowder based military, than those who opposed them, the subsequent result was the rise of colonial superpowers, with the rise of the British and French colonial empires, based on trade. The Spanish empire, which had embarked on imperialism based primarily on looting rather than trade, had failed to innovate and was in decline by this time. Colonialism was driven primarily by economics, and central to capitalism was a growth of inequality and poverty, western powers became richer at the expense of indigenous populations, helping to create the third world. It has been found that societies that industrialised in the modern age have had some of the largest groths ever recorded, for example South Korea is now one of the worlds leading exporters of modern goods, despite being an agricultural society until post the Korean war, in the 1950s, of course western investment has acted to encourage this growth, with the US investing billions to turn the nation into a capitalist paradise, as a result of the Cold war.

So what causes theses societies to change? Unfortunately there is no one theory on this, but rather societal change is influenced by culture, physical environment and politics. Factors such as religion influences cultural, these can act to enhance or reduce the speed of change, such as the demands to translate the Latin bible into English in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, resulting in increased literacy rates for the average population. Culture is also influenced by communication technology, mass communication has encouraged the growth of societies, from the invention of the printing press to the development of the internet. One of the largest influences on culture is the individuals that govern, and influence them, leaders can be seen as an extension of societal desires, a true embodiment of the culture, leaders can be great war leaders, such as Napoleon, or Caesar, scientific and industrial innovators such as Newton or Brunel, or great social motivators, such as Ghandi, Washington or even Jesus. Physical environment motivates social trends due to limited resources, the ancient Egyptian empire relied on agriculture as there were insufficient animals to hunt, whereas native Americans were never encouraged to develop farming based communities due to an excess of bison and buffalo, natural resources also encourage conflict as imperial powers attempt to gain advantage. The influence of politics is also a complex relationship, Marxist theory states that politics are a direct consequence of the economic nature of a society, however there are examples where fundamentally different political organisations have both used capitalists economies, such as Nazi Germany and the US. A far clearer link can be seen as the ultimate expression of political will and its affect on society, the military. Countries like the USSR and North Korea invested vast sums of capital into the development of military might, resulting in a twofold impact on society, due to limited finite resources, investment into the military reduced investment into the welfare and productivity of the nation, having a negative impact on growth, secondly strong aggressive military can lead to a reduction in individual freedoms, acting to reduce creative innovation.

So how does all this relate to the modern world and economics? The western world has emerged due to a decline of traditionalism and a growth of rationalism, key to capitalism is the idea of self improvement, the same idea that drove individuals into the cities is still driving the desires of millions today, the growth of communication technology has freed the individual, people are free to develop their own distinct personality, and own identity. The growth of the same technology has increased the power of the state, allowing governments alter the lives of many in sweeping decisions, such as mass cuts to public spending. The society we live in today may be fundamentally different to societies of the past, but we are the product of our history.

The modern post industrial world is based on globalisation, driven mainly by the growth of ITC and the web. Globalisation has allowed individuals to transcend national borders and have a far greater sense of social responsibility across the globe, for example the web has allowed real time images of natural disasters on the opposite side of the globe, encouraging people to try and help, despite individuals ever likely to even visit the country in question. Wars are no longer fought with the aim of territorial gain, but to protect rights, usually based on western morality. Many have suggested that the web has brought the world closer, but all this has achieved is the flattening of culture, to be replaced by a global culture, based on an Anglo-American ideal, the British empire is far from dead, it just went digital. English is by far the global language of trade, the global language of the web, western imperialism could still be seen as alive and well. Globalisation is the complex marriage of society, economics, technology, and individualism, ideals which the west have long encourage and developed. Trade may have brought prosperity to many second world nations like China, but in an increasingly weightless economy (Quah,1999) the west still holds most of the trump cards.

It is impossible to truly separate sociology and economics, they are intrinsically linked.

Language, Semantics and Pragmatics 1 comment

Reading:

Aitchison, J (1972): Lingusitics, An Introduction. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Thomas, L & Wareing, S (1999): Language, Society and Power: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

Trudgill, P (1983): Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. London: Penguin.

In my last blog post I outlined some of the basic principles of linguistics. This week I will be going into more detail regarding this discipline and attempting to highlight areas of relevance to my topic, Organisation. As I mentioned in both last weeks blog and my initial statement of my intent to study linguistics, I am interested in finding out how language shapes social organisation and forms bonds, both within and between different communities and cultures. This blog post will look at the how language exists and is structured, and then how it can be used on basic levels to encourage and enforce social interaction.

Understanding Language.

Noam Chomsky argued that anyone who has learnt a language must have, at some point in their development, internalised a set of rules regarding the proper use of that language. In some ways, language can be thought of as a game, with rules and players, as well as being turn based. Linguists see language as having a functional role in human life; some examples of these functions are;

- Obtaining information. Eg: “What colour is the sky?” “The sky is blue.”

- Creating action. Eg: “Come with me!”

- Enforcing social bonds. Eg: “Well done!”

Of course language is extremely flexible, and these functions often interact when we are communicating. For example, the conversation:

“Can you go outside and tell me what colour the sky is?”

“Yes…the sky is blue”

“Thank you”

shows language being used to first create action, then to supply information and finally to supply social kudos to the actor. Similarly, the sentence;

“Come with me if you want to live!”

is an example of information being supplied to influence an action. Such common multiplicity in language shows how useful it is in quickly dealing with many different situations which we find ourselves in daily. While many animals have ways of communicating information and action through sound (in fact, the sentence “come with me if you want to live” is one of the most commonly communicated messages in the animal kingdom, next to “we should have sex”), only humans have the capacity to construct complex meaning and abstraction in language. To elaborate, animals communicate what is immediately relevant, such as immediate observations and feelings;

“I am hungry, where is the food?”

“The food is in this tree”

whereas humans can communicate past and future experiences with a descriptive element;

“The banana I ate this morning was delicious!”

“I want a banana too!”

“Well you’ll have to go to the banana tree, climb it, and get one for yourself”

Imagining a solution to a problem is only useful to a society if it can be quickly and effectively communicated to members, and in this respect humans are extremely advantaged thanks to language.

Language construction and semantics.

Language, in its most basic format, is made up of phonemes, which are the smallest sounds which distinguish two words. For example p and b in the English language are phonemes, as they distinguish words such as pit and bit. Phonemes expand to create groups of consonants and vowels, which make up words. Words are then characterised with semantics. Semantics is extremely important in understanding language, as words are far from universally recognisable. Identical words can have far from identical meanings, and humans have evolved to carry out internal logical inference to assess the semantics of a word or sentence. For example, someone who heard the word “duck” while standing on a golf course may logically infer that they need to carry out an immediate action, and someone who heard the same word spoken by a child standing next to a lake might logically infer that the child is referring to the species of bird. Semantics, then, allows us to understand the language we hear and make decisions regarding its usefulness.

Of course, sometimes these decisions are wrong, no matter how logical the thought processes are, and language semantics can become very complicated very quickly. Many words in languages share common semantic components, for example “bull” and “man” both refer to adult male mammals, but we cannot use the terms interchangeably, except as similes. Humans get around this problem of this component overlap in language by working from established prototypes. When one thinks of a bird, one does not tend to think of a penguin, but of a robin, which is closer to the prototypical bird. However, because language is constantly evolving, prototypes can be endemic to certain social groups and certain social settings. If you overhear the word “bird” used by a group of men of a certain age in the local pub, you would be forgiven for assuming that these men are referring to a particular woman, and are not members of your local RSPB branch. This kind of word fuzziness makes logical inference so important when communicating, but shows that it can, on occasion, be incorrect. When humans are unfamiliar with words they hear in a language that they recognise, they can usually solve this problem by asking for clarification; “Excuse me, when you say bird, what do you mean?” and then storing this information as a new internal subset rule of language, something like:

IF SPEAKER= Simon, ENVIRONMENT= Pub, WORD=’Bird’ THEN INFER word= ‘woman’.

And in this way language semantics can constantly evolve and adapt as an individual moves through various social groups and environments.

Pragmatics

Continuing this discussion of the unpredictable nature of language, we can discuss pragmatics. Pragmatics is the study of unpredictable language use, and its creation is commonly attributed to philosopher Paul Grice (1913-1988), who identified efficient communication between humans in four maxims of conversation;

- Quantity: giving the right amount of information when talking.

- Quality: Being truthful when talking if the truth is known.

- Relevance: Relevant answers to questions or relevant statements to contexts.

- Manner: Clear and ordered structuring of communication.

Grice observed that these principles for cooperative communication exist in all languages and are so a core part of communicating, for example when talking to a baby or animal which cannot respond, people will still communicate as if they were expecting a response, and follow one or more of the maxims. However, Grice also observed that the above maxims are often broken, and more commonly by certain social groups within a society. A politician, if we are being pessimistic, may be more inclined to mislead or respond irrelevantly to a question than a scientist. Pragmatic linguists note that when faced with random, useless or simply untrue information in language, humans will often try and draw reasonable conclusions and seek to understand the meaning of what was said, rather than simply rejecting the statement as a failed response. Our minds reason that only matters of extreme importance could cause someone to break the maxims of conversation, for example;

“Did you enjoy your day at school dear? Your maths teacher says that you have been LOOK OUT FOR THAT TIGER!”

And so often people, even when they are aware that laws of conversation have been broken, will allow the speaker to continue, accepting that there must have been a reason for the interruption in normal proceedings, even if the reason is not immediately known.

Pragmatic language therefore has much to say about the power of language, and this explanation of acceptance to broken norms can show us in part why skilled orators, such as lawyers, politicians and journalists, can coerce or influence certain social groups who may or may not be aware of the misuse of language directed at them. We have all seen interviews with politicians who evade certain questions, providing irrelevant answers or random information, and while this may enrage some members of a society, other listeners will assume that there must be a socially beneficial reason for the evasion. These listeners are often of a lower social status than the speaker and have less experience with language on a lexical level (they may not understand the words or the meanings that the speaker is using). I will discuss social classes and language further in two weeks.

What I hope this blog post has shown is that language has laws at a basic level. Language is a construction of sounds, created by humans to achieve certain results. As we evolve, so does the language we use and we are constantly updating our internal rulebook through logical inference to deal with new semantics, situations and social groupings that we find ourselves in. When it comes to use, as long as the basic construction rules are obeyed, language is found to be very flexible, and can be used by those skilled in communication to achieve a variety of ends. However, the basic principles of language and communication are still within us, and it is somewhat comforting to know that, even in a modern world where it new words are constantly created and old ones reinvented, that we still have core uses and needs for language that have remained more or less unchanged since our first words. Although I have not mentioned explicitly my topic of organisation, it is implied through much of the above analysis that language and communication is at the heart of our need to be close to one another, to express emotion, share ideas and survive as a community.

Next week, I will be returning to sociology to discuss sociological theorists and the idea of organisation.

A bit more sociology… Starting to think about gender and sexuality no comments

A little moment to say how I feel:

Haralambos and Holborn’s Sociology. Themes and Perspectives has been recalled back to the library. Sniff. So I am returning it today. We’ve had some good times, but today I have to say goodbye.

So I’m starting to think, why am I doing this? I’m reading these huge (heavy) textbooks and trying to find out what the sociologist’s think about gender and sexuality. But what I have really been trying to concentrate on is why they think these things. What methods have they used to come to these conclusions? That is the most important part of this research, to try to understand how the discipline of sociology applies its methods to individuals and groups to try to understand about gender and sexuality. It seems from this week’s readings that interviews and observation are the favourites for gender and sexuality. There is a certain amount of scientific approach later on (80s onwards) when looking at sexuality, particularly the work of Fausto-Sterling, and this is refreshing, but it always goes back to the interview. How far can a conversation with someone who says that they are a ‘female’, ‘transexual’, ‘male’ really help to explain what gender is I wonder? I’m going to outline, as I do every week, what I have been reading, but I really do wonder if I am going to find anything more about methodological approaches and methods of investigation for sociologists than I have already discovered in these first year undergraduate textbooks. I think that I may need to up the level of reading a little if I am going to get anything more than a broad overview to methods, so far, it has not expanded form last week’s list of:

- participant observation

- quantitative research in the form of surveys, questionnaires and interviews

- qualitative research in the form of interviews and observations

- secondary data

- content analysis

- discourse analysis

- case studies

- life histories

I’m not saying that this isn’t a good list, in fact I think that it covers the social side of human quite well, but there are gaps, when looking at gender, in looking at the physical attributes of individuals and the effects of this on our understanding of gender. What about the genes, and the body, and the brain? Or is this just socio-psychology and I am never going to find the answer I want sitting amongst the sociologists? Craig has given me a book on Social Psychology, which I have been so tempted to read all week; but I am trying to stick with pure sociology for the first few weeks… we’ll see how that goes this week.

Sexuality (and a tiny bit of gender)

There’s just enough time to give a quick review of the chapter on Sex and Gender (Haralambos & Holborn, 2008: 90-142). The section begins with a critique of ‘malestream sociology’ based on the work of P.Abbott, C.Wallace and M. Tyler (2005). There is a mention of the biological differences between man and woman; sexual diomorphism (Haralambos & Holborn, 2008: 92-93), where sexual diomorphism is biological fact (cf. Warton, 2005: 18) and the distinction that sex and gender are different (cf. Stoller, 1968). The chapter discusses the rhesus monkeys from Goy and Pheonix’s experiments (1971) and the work of Archer and Lloyd (2002) on testosterone and criminal records, and goes on to outline Oakley’s criticism of the rhesus monkey experiemnts as not including the social context affecting the hormone levels (1981) and also Halpern et al. work on aggression and testosterone in teenage boys (1994) that shows there is no correlation between testosterone levels and aggression. Archer and Lloyd say that although hormones contribute to aggressive behaviour, peer groups also affect behaviour, they say that there is an ‘interaction between biological and social processes (Archer and Lloyd, 2002). I think that this is interesting when considering the representation of gender online as the communication between groups needs to be considered when thinking about the way that an individual is choosing to present themselves (or feels that they have to present themselves) online.

Haralambos and Holborn go on to discuss sociobiology (2008: 94-96). This is a topic that I am going to read more into as I think that it will have a lot to say about the links between genetics and behaviour and therefore could be useful when thinking about the presentation of sexual identity online. Barash applies Wilson’s worn on sociobiology to gender and sex (Barash, 1979; Wilson, 1975) saying that reproductive strategies produce different behaviours between males and females, resulting in different social roles. Looking at the literature for this subject available in the University of Southampton library, sociobiologists seem to use animal behaviour to explain their theories, and it seems to me that this may not therefore wash when you move the theories across to humans. Blier writes against sociobiology, saying that they are ethnocentric (1984), this is a really interesting point. If studying different societies results in different behaviours of men and women being observed, does this necessarily mean that sociobiology is wrong? Or does it mean that there are other factors at play that have resulted in an exceptional situation occurring? I don’t agree with this, but I am saying it as the internet is an exceptional situation perhaps? And so the work of sociobiologists, whether true or false in its statements, becomes irrelevant when all of the social norms are being broken and the communities are abnormal? Looking at whether communities online are abnormal or not isn’t within the scope of this little project; I wish it was as I believe that they are not abnormal and that the world online is an exact copy of the world offline.

Haralambos and Holborn go on to discuss the sexual division of labour (cf. G.P.Murdock, 1949) and also the cultural division of labour (cf. A.Oakley, 1974). Oakley looks to disprove Murdock’s idea that biology determines the division of labour between the sexes, she does this by looking at the labour divisions of a range of societies (1974), but again, she is using the sociologist’s approach of studying the behaviours of societies and then concluding that they are representative of all of the individuals, past and present, on earth. Oakley identifies where socialisation into gender roles occurs: manipulation of child’s self-concept; canalization of boys and girls using objects; verbal appellations for children; exposure to different activities (1974). But, as Haralambos and Holborn point out, Oakley misses the other reasons for this behaviour; Connell points out that it is not always passive, consider the active seeking out of pleasure he says (i.e. wanting to wear high heels because they make you feel sexy)(Connell, 2002:138-141) – not sure about this one: why do you feel sexy in high heels? Because of the societal behaviours, this is not an active seeking out, this is a passive enforced behaviour, I think.

The chapter then moves onto gender attribution, in particular the work of Kessler and McKenna, ethnomethodologists who look at how people characterise the world around them, where gender is socially produced, and that there is therefore no way to tell between a woman and a man easily (Kessler & McKenna, 1978:885-7). It seems to me that they come to some of their conclusions using interviews to think about how transsexuals remove their perceived sexuality by others from their actual physical attributes that may make an individual make an assumption about their sexuality. This is done by: content and manner of speech; public physical appearance; information about their past life; private body and how to hide details of their body that would point to a particular sexuality (Kessler & McKenna, 1978). This is very interesting in the online world. Where do these four processes happen when you are online? The private body is easier to conceal, but I would argue that the manner and content of speech, the public physical appearance (assuming that it has to be chosen by the individual from a selection of possibilities, as in SecondLife) and the past life are all just as difficult to construct online as they are offline. I think that we are just as constrained by these processes online as we are offline.

Haralambos and Holborn introduce Fausto-Sterling and the idea of transgendered people, where dualistic views of being either male of female are not appropriate (Fausto-Sterling, 2000), her work is also based in the social processes that create gender, she says that gender is ‘embodied’. Key to this is that the development of neural processes in the brain is connected to the experiences we have, so our social factors and our body’s factors reinforcing one another so that gender is materialised within the body (Fausto-Sterling, 2000). The section ends with Connell’s idea that biology and culture are fused together (Connell, 2002).

Next Week

Feminism is discussed in depth in the introductory textbooks that I am using for this early stage of my reading. I am going to read through Abbott et al., 2005. An Introduction to Sociology. Feminist Perspectives, for this part of my research. I know that I said that I would do it last week, but I have been quite surprised at how useful the undergraduate textbooks have been. I am going to try to move onto biology also this coming week, I have the texts that I identified last week sitting on my desk staring at me. I am loathe to start them as I think that I know already what they will contain…