It isn’t hard to find similarities between the British Isles and New Zealand. The traditions derived from the British immigration to the islands (and the South Island in particular) emerge as a common language; as familiar sports at which, for the most part, the Kiwis give us a good thumping; a liking for real ale, often locally brewed; ‘fish & chips’ and, of course, sheep (and cows). There are still more sheep than people in New Zealand although the current ratio (6:1) is not as fleecy as it once was (22:1 in 1982) partly due to depressed wool prices, a significant switch to irrigation-based dairying (more later) and to human population growth. The latter has been concentrated in the more strongly Polynesian North Island and especially in the City of Auckland region which now holds a whopping 30% of the country’s 4.7 million people. This, of course, makes the rest of the country pleasingly empty – if you’re a claustrophobe. Given that London ‘only’ comprises 13% of the UK population, the dominance of Auckland as an increasingly concentrated centre of population, and therefore energy demand, provides another parallel with Britain albeit, rather more extreme.

Renewable electricity

Lake Manapouri Hydro scheme intake, Fiordland

There are similarities too in some forms of energy production. Overall New Zealand is self-sufficient in most fuel sources (coal, renewables, waste heat) with the exception of oil. Electricity production is now 85% ‘renewable’ (& aiming for 100% by 2035) with substantial hydro-electric (~57% of generation), geothermal, wind and increasingly photovoltaic investments. The latter has seen rapid growth in the complete absence of any kind of ‘green’ subsidy or market incentives and has led some to question whether traditional economic ‘rational actor’ models can explain such ‘economically irrational‘ behaviour.

Cook Strait: perhaps the greatest tidal/marine hydro potential & the best white horses around?

As a result, if the hydro-electric powered aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point were to close, there would be a substantial overall surplus although of course an overall (average) surplus does not equate to being able to deliver during periods of peak demand.

This goes some way to explaining the relative lack of interest in the ex

Wairakei Geothermal power station – dates from 1958 and was the first of its kind in the world.

treme tidal currents of the Cook Strait that separates the islands. The currents are sufficiently strong that scuba divers have been known to wash up (alive) on remote beaches tens of miles but only 30 minutes by sea current from their starting points. Since the average crowded beach in New Zealand comprises 0.25 of a car, a few sea lions, the odd penguin and a pair of highly territorial oystercatchers this can make it tricky to get home! It is hardly surprising then that research has yet to devise a generation technology that can survive in the conditions for long.

Nuclear it seems is not just off the cards but completely off the table and its baseload generation is replaced by geothermal plants in the volcanically active North Island – miles of shining pipes, hot steam and some highly dubious smells.

Demand response and responsive demand

However, the reliance on hydro, wind and increasingly solar for electricity generation does put the system at the mercy of variable rainfall, wind and sunshine thus severely increasing the risks of generation shortage in specific seasons and at particular times of day.

Much like some parts of the south of the UK, lines companies (DNOs) in NZ are anticipating potential risks of mid-day overload where local photovoltaic generation is not matched by local demand. In response a number of academic and commercial projects are exploring ways to either incentivise time-shifting of demand, directly control consumption or provide large scale storage.

Unlike the UK, New Zealanders are familiar with various forms of direct load control either for hot water heating where electricity dominates, or for some form of space heating. In addition heat pumps are also now increasingly being installed in both new and old dwellings alike and taken together these trends make New Zealand an ideal ‘research lab’ for smart grid ideas – and assessments of consumers’ adaptive responses to them.

Heat, damp and death

For many in the energy research and policy sectors however, domestic power demand is essentially a sideshow compared to the very poor state of the country’s housing stock which in large part is very poorly insulated and therefore damp with known implications for poor health, especially for the elderly and fuel poor. Double-glazing is rare, heat is often provided to just one (living) room and rental properties are not required to have either insulation or heating reflecting known patterns of excess winter deaths despite the temperate climate.

In the North Island, and in hot and humid Auckland in particular, summer cooling takes over from winter heat as a significant (new) energy demand. However, while the health implications of poor housing conditions are inarguable, a number of commentators have lamented that increasing ‘comfort’ should be culturally bracketed with a trend away from ‘traditional’ New Zealand virtues of ‘toughness’ and ‘thrift’.

Of trucks and trains

The truck stops here (and everywhere else)

In the case of transport (40% of all NZ energy sector GHG emissions) the almost total dependence on air travel and roads as means of mobility both for people, goods and sheep is inscribed in the dependence on oil imports, dwarfing residential energy demand (11% of all energy use) in gross terms.

Such is the infrequency of rail transport that tracks regularly route through the middle of roundabouts on major highways and sometimes even ‘time-share’ single lane road bridges with occasionally hilarious if slightly hair-raising results.

Yet another integrated roundabout & railway crossing on State Highway 6

Hardly surprisingly taxes on fuel are the 5th lowest in the OECD as policy is to protect haulage and farming interests as well as greasing the wheels of mobile and consumption based capitalism.

The climate crunch

New Zealand has per capita carbon emission levels similar to the UK but substantially lower than both Australia and the USA. The low emissions due to electricity generation from largely renewable sources counteracts the oil dependence of the transport sector and is helped along, according to some, by a penchant for hair shirts and ‘austerity’.

Carbon however is not the whole story. New Zealand’s agricultural system means that per capita methane and nitrous oxide emissions are, like Australia, significantly higher than those of both the UK and the USA. Despite emitting less than 6% of the USA’s total and less than 0.6% in the case of carbon dioxide, the New Zealand government is coming under increasing domestic and international political pressure to be seen to be doing something (anything!) to combat both carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions.

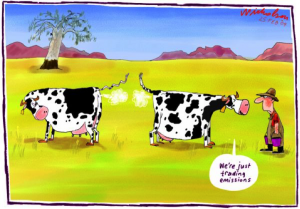

The only other way to cut NZ’s greenhouse emissions – killing cows

And here’s the problem: current consensus is that there are essentially only two ways to significantly cut New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions: de-carbonising transport and/or killing cows.

Whilst sheep (6 per person) still outnumber cows (2 pp) not to mention the remaining 68,000 Kiwi (0.01 pp), the growth of intensive dairy production not only risks a number of resources that New Zealanders take as ‘given’ such as clean rivers, lakes and seas for fishing & swimming and plentiful fresh water but it also produces methane by the belch-full. There is, however, little appetite for undermining New Zealand’s biggest export earner, the $14+ billion dairy export industry.

Thus, whilst ongoing research is looking at ways to adjust feedstuffs to reduce methane effluent, or to channel waste into bio-energy, the main ‘greenhouse gas policy’ focus is firmly on transport. Recent concerns over the security of oil supplies that predominantly originate in the Middle East, Brunei and Russia together with, amongst other things, the ‘thrift-driven’ desire to hang on to inefficient ‘old bangers’ have come together in a number of ‘future transport’ fora with transformation in mind. To date however these have run headlong into the ‘low tax’ high-oil-dependency transport sector reflecting rather low-key policy ambitions although the new green-tinged coalition government may take bigger steps.

There is clearly much to do.

Further reading

Try:

- Otago Energy Research Centre

- New Zealand National Energy Research Institute

- New Zealand Smart Grid Forum

- The Centre for Sustainability’s Energy Research programme

About

Ben Anderson is currently in New Zealand as a EU H2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Global Fellow hosted at the Centre for Sustainability at the University of Otago in Dunedin.