A practical, tools-based course designed for repository managers and presented by expert tutors, in five parts between January and March 2010, in the UK. This distinctive new course starts Tuesday 19 January 2010, in Southampton, UK.

Update (12 January 2010). This course is now full. Places for individual modules may be available on request.

Includes a ground-breaking tutorial on joined-up tools for preservation management workflow for repositories.

This free course is presented by the JISC KeepIt project in association with Digital Curation Centre, and the European-wide Planets project.

Update (11 February 2010): venues added for modules 3 and 5.

Update (30 September 2010): a full record is available for this course.

Why Digital Preservation?

Digital preservation, the ability to manage content effectively and ensure continued access over time, is an implicit commitment made by an institution to those who deposit their important and valuable content in its repository. It’s also an asset for a repository to be able demonstrate to its users good quality content management processes embracing preservation.

Digital preservation, the ability to manage content effectively and ensure continued access over time, is an implicit commitment made by an institution to those who deposit their important and valuable content in its repository. It’s also an asset for a repository to be able demonstrate to its users good quality content management processes embracing preservation.

About the course

Digital preservation is currently well served with training courses that are strong on the foundations of the topic, and are aimed at a general audience. This KeepIt course, designed to create repository preservation exemplars in the UK, makes more specific assumptions about the working environment – digital institutional repositories – and will specialise in working with tools optimised for this environment. The course is applicable to all popular repository types, although one part on preservation workflow is currently implemented and optimised for EPrints.

The course is structured to place repositories and their preservation needs within an organisational and financial framework, culminating in hands-on work with a ground-breaking series of tools to manage a repository preservation workflow. A tutorial on these tools was first presented at a major European conference (ECDL) and is now brought to the UK for the first time. With repositories ready to become preservation exemplars, the course concludes by considering issues of trust between repository, users and services.

Each module will give extensive coverage of chosen topics and tools through presentation, practical exercises, group work and feedback.

The first and fourth modules will be held in Southampton. Other venues to be announced. Some or all will be in Southampton, the home of the KeepIt project. The modules each last a single day, apart from module 4 on the preservation workflow, which will last two days and includes an evening social event.

Course outline

Five modules formed around: organisational issues, costs, description, tools, and trust.

Tues. 19 January 2010

- Module 1. Organisational issues, Southampton. Will will seek to connect institutional repository objectives with an emerging preservation architecture. Topics will include audit, selection and appraisal.

Fri. 5th February

- Module 2. Costs, Southampton. The focus will be lifecycle costs for managing digital objects, based on the LIFE approach, and institutional costs, extending to policy implications.

Tues. 2nd March

- Module 3. Description, London. Describing content for preservation. This has two parts (not mutually exclusive):

- 3.1 User description: provenance, and significant properties

- 3.2 Service-based description: formats, preservation metadata

Thurs. 18th-Fri. 19th March

- Module 4. Tools, Southampton. This will be based on the earlier ECDL tutorial, and will cover the tools available in EPrints for format management, risk assessment and storage, and linked to the Plato planning tool from Planets.

Tues. 30th March

- Module 5. Trust, Northampton. There are two angles here: trust (by others) of the repository’s approach to preservation; trust (by the repository) of the tools and services it chooses. This will connect us with users and services.

Expert tutors include:

- Neil Beagrie (consultant, Charles Beagrie Ltd)

- Joy Davidson (Digital Curation Centre)

- Brian Hole (British Library)

- Sarah Jones (DCC)

- Ed Pinsent (University of London Computer Centre, and DPTP)

- Andreas Rauber (Vienna University of Technology, and Planets project)

- David Tarrant (University of Southampton)

- Stephen Grace, Gareth Knight (Kings College London)

More tutors to be announced.

Join us to make your repository an exemplar preservation repository.

Contact for signing up: If you are interested in participating in this course, in the first instance contact Steve Hitchcock, KeepIt project manager, to register. Please advise of your role with the repository. Places are limited for practical training purposes.

Information for delegates

The course is aimed at institutional repository managers and other members of repository management teams, and does not require prior knowledge of digital preservation or specific technical expertise. Only a working knowledge of repository content management is assumed.

To get the full benefit of the course it is recommended that repositories sign up for all five modules, and preference will be given to repositories that can do so. Since the course emphasises a structured, joined-up approach, it will benefit repositories to be represented by the same person throughout, but this is not essential.

Following the course there will be optional follow-up sessions to assist and evaluate uptake of the tools within the repositories and to brief other members of repository teams.

The course is largely independent of any particular repository software, but one section of the course (part of module 4) will use EPrints as the available tools will have been integrated with this platform. At all stages the course will use available tools to emphasise practical developments and to assist subsequent application and uptake.

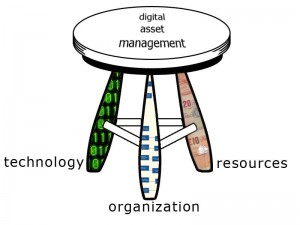

Nobody has asked the question – perhaps it doesn’t need asking after KeepIt course 1 – but why did a course on digital preservation start with organisational issues? Recently a new report was published by the Digital Curation Centre, and I will pick out one section that answers that question:

Nobody has asked the question – perhaps it doesn’t need asking after KeepIt course 1 – but why did a course on digital preservation start with organisational issues? Recently a new report was published by the Digital Curation Centre, and I will pick out one section that answers that question:

Recent Comments