Archive for the ‘Anthropology’ tag

Ethnography 3 – Methodologies & Analysis no comments

Researcher: Jo Munson

Title: Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?

Disciplines: Economics, Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

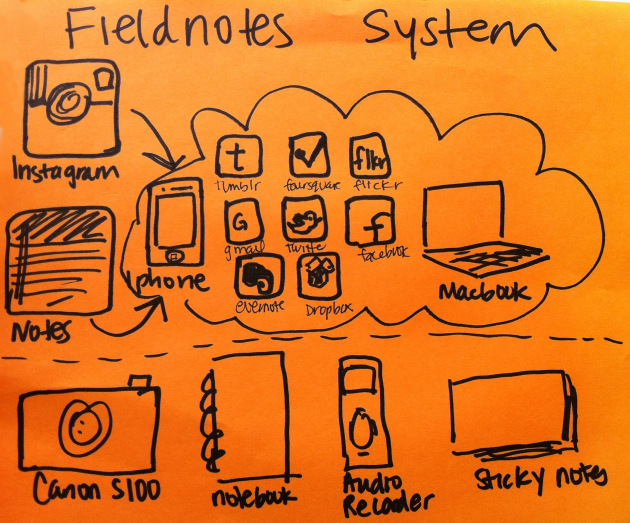

How one modern Ethnographer uses technology to perform fieldwork.

Methodologies in Ethnography

The primary method of collecting data and information about human cultures in Ethnography is through fieldwork, although comparison of different cultures and reflecting on historical data is also important in Ethnographic methodology. The majority of Ethnographic research is qualitative in nature, reflecting its position as a social science. Ethnographers do however make attempts to collect quantitative data, particularly when trying to take a census of a community and in comparative studies.

The methods used to collect information can be broadly categorised as follows:

Fieldwork methods:

- Observation, Participant Observation & Participation – a feature of nearly all fieldwork, Observation can vary from a high level recording of events without interacting with the community to becoming wholly immersed in the community. The latter can take months or even years and will usually require the Ethnographer to learn the language of, and build relationships with the locals.

- Survey & Interview – surveys can be structured with fixed questions (often used at the start of a fieldwork placement), or unstructured, giving the interviewee an opportunity to guide the direction of his or her answers.

Comparative methods:

- Ethnohistory – Ethnohistory involves studying historical Ethnographic writings and ethnographic or archaeological data to draw conclusions about an historic culture. The field is distinct from History in that the Ethnohistorian seeks to recreate the cultural situation from the perspective of those members of the community (takes an Emic approach).

Unlike Observation / Participation and Survey, Ethnohistory need not be done “in the field”. Ethnohistory has become increasingly important as it can give valuable insight in to the speed and form of the “evolution” of societies over time. - Cross-cultural Comparison – Cross-cultural Comparison involves the application of statistics to data collected about more than one culture or cultural variable. The major limitations of Cross-cultural Comparison are that it is ahistoric (assumes that a culture does not change over time) and that it relies on some subjective classifications of the data to be analysed by the Ethnographer.

Sources of bias

The sources of bias in Ethnographic data collection can be substantial and often unavoidable, some of the most common are:

- Skewed (non-representative) sampling – samples can be skewed for many reasons. Sample sizes are often small, so the selection of any one interviewee may not be representative of the population. The Ethnographer can also only be in one place and will often make generalisations about the whole community based on the small section he or she interacts with. The Ethnographer is also limited to the snapshot in time that he or she observes the community.

- Theoretical biases – the method of stating a hypothesis prior to investigation may cause the Ethnographer to only collect data consistent with their viewpoint relative to the initial hypothesis.

- Personal biases – whilst Ethnographers are acutely aware of the effect their own upbringing may have on their objectivity (think Relativism), this awareness does not stop prior beliefs having an effect on data collection.

- Ethical considerations – Ethnographers may uncover information that could compromise the cultural integrity of the community being observed and may choose to play this down to protect their informants.

Interpreting Ethnographic research findings

Whilst there is no consensus on evaluation standards in Ethnography, Laurel Richardson has proposed five criteria that could be used to evaluate the contribution of Ethnographic findings:

-

Substantive Contribution: “Does the piece contribute to our understanding of social-life?”

Aesthetic Merit: “Does this piece succeed aesthetically?”

Reflexivity: “How did the author come to write this text…Is there adequate self-awareness and self-exposure for the reader to make judgments about the point of view?”

Impact: “Does this affect me? Emotionally? Intellectually?” Does it move me?

Expresses a Reality: “Does it seem ‘true’—a credible account of a cultural, social, individual, or communal sense of the ‘real’?”

These reflections, alongside the statistical output of quantitative or Cross-cultural Comparative study can be used to reform Ethnographic theories and gain insight into human culture.

Next time (and beyond)…

The order/form of these may alter, but broadly, I will be covering the following in the proceeding weeks:

Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?Ethnography 1 – Introduction & DefinitionEthnography 2 – Disciplinary ApproachEconomics 1 – Introduction & DefinitionEconomics 2 – Disciplinary Approach, the Big TheoriesEthnography 3 – Methodologies & Analysis- Economics 3 – Modelling & Methodologies

- Ethnographic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Ethno-Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

Sources

The American Society for Ethnohistory. 2013. Frequently Asked Questions. [online] Available at: http://www.ethnohistory.org/frequently-asked-questions/ [Accessed: 31 Oct 2013].

Umanitoba.ca. 2013. Objectivity in Ethnography. [online] Available at: http://www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts/anthropology/courses/122/module1/objectivity.html [Accessed: 31 Oct 2013].

Peoples, J. and Bailey, G. 1997. Humanity. Belmont, CA: West/Wadsworth.

Richardson, L. 2000. Evaluating Ethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 6 (2), pp. 253-255. Available from: doi: 10.1177/107780040000600207 [Accessed: 31 Oct 2013].

Image retrieved from: http://ethnographymatters.net/tag/instagram/

What is Anthropology Part 2: Theories and Fields no comments

Eriksen, T. H., 2004. What is Anthropology. London: Pluto Press.

“The raw material of anthropology – people, societies, cultures – is constituted differently from that of the natural and quantitative sciences, and can be formalised only with great difficulty…” (Eriksen, 2004, p 77). “[Anthropology’s approach] can be summed up as an insistence on regarding social and cultural life from within, a field method largely based on interpretation, and a belief (albeit variable) in comparison as a source of theoretical understanding” (Eriksen, 2004, p 81). Theory provides criteria by which to categorise data and to judge is significance. Anthropology applies theory to social and cultural data.

Fundamental questions

1. What is it that makes people do whatever they do?

2. How are societies or cultures integrated?

3 To what extent does thought vary from society to society, and how much is similar across cultures?

Anthropological theory is deeply tied to observation. Differences in approaches by region: US researchers favour linguistics and psychology and British favour sociological explanations (via politics, kinship and law).

Theory

There are 4 main theoretical underpinnings of Anthropological theory:

1. Structural-functionalism – A R Radcliffe-Brown: Demonstrating how societies are integrated. Person as social product. Ability of norms and social structure to regulate human interaction. Social structure defined as the sum of mutually defined statuses in a society.

2. Cultural-materialism – Ruth Benedict (1887-1948): Cultures and societies have ‘personality traits’.

Dionysian = extroverted, pleasure seeking, passionate and violent;

Apollonian = introverted, peaceful and puritanical;

Paranoid = members live in fear and suspicion of each other. Culture expressed seamlessly in different contexts – from institutional to personal levels.

Margaret Mead (1901 – 1978): sought to understand cultural variations in personality. Her highly influential work on child-rearing, Coming of Age in Samoa (1928) demonstrated that personality is shaped through socialisation.

3. Agency and society

Raymond Firth: Persons act according to their own will.

Pierre Bourdieu: Interested in the power differences in society distributed opportunities for choice unequally. Knowledge management: Doxa = what is self-evident and taken for granted within a particular society; Habitus = embodied knowledge, the habits and skills of the body which are taken for granted and hard to change; Opinion = everything that is actively discussed; Structuring structures = the systems of social relations within society which reduce individual freedom of choice. Important to understanding the causes that restrict free choice.

4. Structuralism – Theory of human cognitive processes.

Lévi-Strauss: the human mind functions and understands the world through contrasts in the form of extreme opposites with an intermediate stage (‘triads’). Cross-cultural studies of myth, food, art classification and religion. Based on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s observation in La pensée sauvage: “…in order to study Man, one must learn to look from afar; one must first observe differences in order to to discover attributes”. Post-structuralism more in favour today.

5. Primacy of the material – Strongly influenced by historical materialism (Marx). Gives primacy to material conditions of individuals above individual agency or how the mind works.

Two approaches within this area: those that favour economic conditions and those that give primacy to technological and ecological factors.

Julian Steward/Leslie White: Societies grow in complexity as a result of technological and economic change. Change happens in the ‘cultural core’ of technology, ecological adaption and property relations. The ‘rest of culture’ (e.g. religion, art, law etc) is more or less autonomous.

Gregory Bateson (Margaret Mead’s husband and one of the founders of cybernetics – i.e self-regulating systems) – all systems have properties in common: reaction to feedback (or lack of feedback) gives rise to repercussions which ensures the continuing re-imaging of the system.

6. Geertzian hermeneutics – interpretation of the world from the natives point of view.

Clifford Geertz: Thick description = a great deal of contextual description to elicit understanding of data. “…research primarily consists of penetrating, understanding and describing culture systematically the way it is experienced locally – not to explain it in terms of comparison…structuralist, materialist, or otherwise.”

Culture is expressed through shared, public symbols (communication) – so guessing the workings of the minds of those under scrutiny is unnecessary.

7. Eclecticism – a combined approach which recognises the complexity of the world and which attempts to “grasp both the acting individuals and the systemic properties constraining them”.

Fields

1. Reciprocity – the conduct of exchange, fundamental to sociality, crucial to human life.

a) Marcel Mauss – Gift-giving. The Gift (Essai sur le don, 1925). Three roles in gift-giving: obligation to give, obligation to receive and obligation to return the gift. Simplistic evolutionary view of society: i) Universal gift-giving fundamental to social integration (historical) ii) Institutions take on gift-giving role. iii) Marginal role for gift-giving in modern, alienating, capitalist societies. Exchange does not need to be economically profitable. “All economies have a local, moral, cultural element” (Eriksen, 2004, p 88). (Remnants of historical obligation are witnessed in round buying in pubs, dinner party invitations, circulation of second-hand children’s clothing among family and friends, voluntary community work, and Christmas. The potlatch institution (Boas) – where tribes seek to out-do each other in their extravagant wastefulness.

b) Karl Polanyi – Integration: reciprocity, redistribution and market principle. A radical critique of capitalism, directly relevant to ‘economic anthropology’. Rejects the view that people primarily strive to maximise utility (even if it happens at the expense of others). Psychological motivations are influenced by personal gain, consideration for others and the need to be socially acceptable. “Reciprocity is the ‘glue’ that keeps societies together” (Eriksen, 2004, p 91).

c) Marhsall Sahlins – 3 forms of reciprocity: balanced (e.g. tit-for-tat trade – close proximity ), generalised (gift-giving – family and friends), and negative (attempt to gain benefit without cost – strangers). Shows how “morality, economics and social integration are interwoven” (Eriksen, 2004, p 92).

d) Annette Weiner (Inalienable Possessions, 1992) – some things cannot be exchanged or given away as gifts, e.g. “…talismans, knowledges, [secret] rites which confirm deep-seated identities and their continuity through time” (Maurice Godlier, 1999). Cultural identity could be seen as an ‘inalienable possession’.

e) Daniel Miller (Theory of Shopping, 1998) – Sacrifice: women in buying at supermarkets purchase for others to form a relationship with them, and consider the views of others when buying for themselves.

f) Matt Ridley (The Origins of Virtue, 1996) – mathematical models show that cooperation ‘pays off’ in the long run.

2. Kinship – basis of social organisation. Not just family, but local community and work relations.

a) Lewis Henry Morgan – traditional societies thoroughly organised on kinship and descent.

b) Fortes and Evans-Pritchard – acephalous (‘headless) societies in Africa based on kinship-based social organisation. Segmentary system that expands and shrinks according to need – deeply influential in anthropology.

c) Lévi-Strauss – Alliance and reciprocity in kinship relations. Marriage in traditional societies is group-based and forms long-term reciprocity.

d) ‘Modern’ society – tension between family, kinship and personal freedom. Kinship is important in determining career opportunities

3. Nature

a) Inner nature – humans shaped by society and history, but with objective, universal human needs (Malinowski, Lévi-Strauss).

b) External nature – relationship between ecology and society, options are limited by environmental conditions, technology and population density.

c) Nature as a social construction – humans create representations of nature, which is often unspoken or not reflected upon – tacit knowledge.

d) Sociobiology – human actions cannot be be understood as pure adaption. “Research aims to establish valid generalisations about the mind as it has evolved biologically”.

4. Thought – people say what they think or express it through their acts, rituals or public performances.

a) Rationality – Evans-Pritchard’s 3 types of knowledge: i) mystical knowledge based on the belief in invisible and unverifiable forces; ii) commonsensical knowledge based on everyday experience; iii) scientific knowledge based on the tenets of logic and experimental method. Important, possibly unanswerable questions: i) is it possible to translate from one system of knowledge to another without distorting it with ‘alien’ concepts? ii) does a context-independent or neutral language exist to describe systems of knowledge? iii) do all humans reason in fundamentally the same way? Study of Technology and Science (STS) – science and technology as cultural products.

b) Classification and pollution – different people classify and subdivide them in different ways. Mary Douglas: classification of nature and the human body reflects society’s ideology about itself. What ‘pollution’, i.e. food prohibition, tells us about society.

c) Totemism – a form of classification whereby individuals or groups have special (often mythical) relationships to nature. Lévi-Strauss’ distinction between bricolage (associational, non-linear thought) and ‘engineering’ (logical thought).

d) Thought and technology

5. Identification a) The social b) Relational and situational identifications c) Imperative and chosen identities d) Degrees of identification e) Anomolies

Mind map: http://www.mindmeister.com/250242069

Ethnography 2 – Disciplinary Approach no comments

Researcher: Jo Munson

Title: Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?

Disciplines: Economics, Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

Ethnographers concern themselves with studying the

cultural differences and similarities between humans

An Ethnographer’s approach to studying humanity

Remembering then that Ethnography can be thought of as:

the study of contemporary and recent human societies and cultures

and that:

culture is the socially transmitted knowledge and behavioural patterns shared by some group of people

I now consider what makes Ethnogaphers’ approach to the study of humans distinct from that of say, Sociologists. There are three concepts particularly central to Ethnographic study:

- Holism – the concept that no one aspect of a society can be understood without understanding how it relates to all other aspects of that community.

- Relativism – the concept that the observer of a community should not judge the observed community with the prejudices and values of their own culture.

- Comparativism – the concept that for something to be considered “universal” to all humans, the diversity of global human culture must have been considered.

Relativism and Comparitivism together highlight a particular feature observed amonghst Ethnographers – they tend to fall somewhere between two extremes:

- Relativists – who concentrate on cultural differences between human socities; and

- Anti-Relatives – who concentrate on the similarities between cultures, or “human universals”.

The approaches and theories of Cultural Anthropologists has evolved over time, with Evolutionary and Functionalist ideas making way for new ideas. In the same way that Ethnographers can be thought of as Relativist or Anti-Relativist, modern Anthropology considers Materialism and Idealism:

- Materialists – Materialists believe that the material features of a community’s environment are the most important factor affecting its culture.

- Idealists – Idealists believe that human ideas affect culture more than any material features.

As with all extremes, the reality is more likely a mix of the two opposing schools of thought.

Next time (and beyond)…

The order/form of these may alter, but broadly, I will be covering the following in the proceeding weeks:

Can there ever be a “cohesive global web”?Ethnography 1 – Introduction & DefinitionEthnography 2 – Disciplinary Approach- Ethnography 3 – Theories & Methodologies

- Economics 1 – Introduction & Definition

- Economics 2 – Disciplinary Approach

- Economics 3 – Theories & Methodologies

- Ethnographic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Ethno-Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

Sources

Peoples, J. and Bailey, G. 1997. Humanity. Belmont, CA: West/Wadsworth.

Barnard, A. 2000. Social anthropology. Taunton: Studymates.

Image retrieved from: http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/multimedia/photo_gallery/0908/nba.cbk.remember.when.hoops.style/content.1.html

Ethnography 1 – Introduction & Definition no comments

Researcher: Jo Munson

Title: Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?

Disciplines: Economics, Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

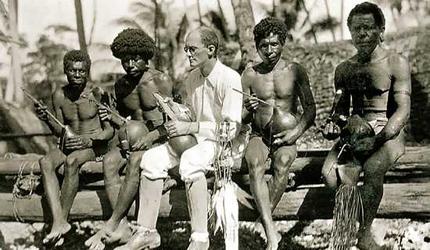

The archetypal vision of Anthropological fieldwork – but times have changed…

A very brief introduction to Anthropology

Cultural Anthropology forms one of the 5 pillars of the broader field of Anthropology, namely:

- Physical Anthropology (also called Biological Anthropology)

- Archaeology

- Anthropological Linguistics

- Applied Anthropology

- Ethnography (Also known as Cultural Anthropology Social Anthropology1)

Common to all Anthropologists is their fascination with human kind.

The scope of Anthropological study is enormous:

- Physical Anthropologists focus on the evolution of our species and the anatomical differences between different races;

- Archaeologists lean towards analysing humans through the material remains we leave; and

- Anthropological Linguists are interested in how our use of language reflects our view of our surroundings, our social hierarchy and social interactions.

Regardless of the application or particular nuance each sub field takes on, the focus is always on finding out more about human beings.

The traditional view of the Anthropologist in the field is the Caucasian middle-aged man living among the tribal peoples of Africa, but this no longer reflects the discipline.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, there began a shift from (predominantly Euro-American Anthropologists) exclusively studying pre-industrial, non-western populations to the study of cultures “closer to home”. The shift reflected the realisation that Anthropologists offer unique insights to society as a whole, not covered by fields such as Sociology. Further more, Anthropology has begun to gain credibility as an applied discipline useful in solving “real world” problems, no longer confined to the realms of academia.

What then, are the particular features that define Ethnography?

[1] Strictly speaking, many argue that Social Anthropology is distinct from Cultural Anthropology. The distinction is not universally defined but some suggest that historically, US Anthropologists have focused more on cultural differences between populations (and commonly adopt the term Cultural Anthropology), whilst UK Anthropologist look more at societal differences (and more commonly use the term Social Anthropology).

Definition: Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

Ethnography has been defined as “the study of contemporary and recent human societies and cultures.” where the concept and diversity of culture is central to Ethnographic study. It is further suggested that:

Describing and attempting to understand and explain this cultural diversity of one of [Ethnographers’] major objective. Making the public aware and tolerant of the cultural differences that exist within humanity is another mission of Ethnology.

I think this summarises the objectives of Ethnography clearly, although does lead me to ask what “culture” is to an Ethnographer.

Anthropological definition of culture

Culture has been defined in countless ways by Anthropologists. One formal definition that has been suggested is that:

Culture is the socially transmitted knowledge and behavioural patterns shared by some group of people

That is to say that culture is not defined by biology or race, but is defined by the environment in which we live. Culture is learned from other people in our social group, knowledge is shared such that the group can reproduce and understand one another and behavioural patterns are assumed such that the group functions well, with each member playing their role.

Culture is of course a far more complex concept than described above, but this gives an idea about what is important to an Ethnographer’s studies. In essence, the Ethnographer studies what is important to the human and the human’s social group, including what allows the group to function and what might challenge harmony within the group.

Next time (and beyond)…

The order/form of these may alter, but broadly, I will be covering the following in the proceeding weeks:

Can there ever be a “cohesive global web”?Ethnography 1 – Introduction & Definition- Ethnography 2 – Disciplinary Approach

- Ethnography 3 – Theories & Methodologies

- Economics 1 – Introduction & Definition

- Economics 2 – Disciplinary Approach

- Economics 3 – Theories & Methodologies

- Ethnographic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Ethno-Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

Sources

Peoples, J. and Bailey, G. 1997. Humanity. Belmont, CA: West/Wadsworth.

Barnard, A. 2000. Social anthropology. Taunton: Studymates.

Image retrieved from: http://sumananthromaterials.blogspot.co.uk/2010/06/social-and-cultural-anthropology.html

Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”? no comments

Researcher: Jo Munson

Title: Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?

Disciplines: Economics, Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

Is now the time for a transparency and global cooperation on the web?

Can there ever be a “cohesive global web”?

The web is more a social creation than a technical one. I designed it for a social effect — to help people work together — and not as a technical toy. The ultimate goal of the Web is to support and improve our weblike existence in the world. We clump into families, associations, and companies. We develop trust across the miles and distrust around the corner.

A hopeful inditement of the web’s potential from the “father of the web”, Sir Tim Berners Lee (Tim BL), but unfortunately, we are developing mistrust on the web. Whether or not it was the intention of Tim BL and other pioneers of the internet and the web, the power over the infrastructure and development of the web has long been routed in the Western English speaking world.

As the rest of the world has begun to engage with, depend upon and contribute to the web, the US/UK-centric view of the web is being challenged. This distrust for a web where 80% of web traffic is passed through US servers is not limited to the likes of the ever elusive and separatist nations such as North Korea, but by some of the largest economies in the world. Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff voiced her dismay at the NSA’s “miuse” of the web to spy on her private email and correspondence and duly threatened to install Fibre-optic submarine cables that link Brazil directly with Europe, bypassing the current connection via a single building in Miami. German, Mexican and French leaders are also outraged by being victims of the NSA’s “snooping”.

The world’s second largest economy, China, has long dissociated itself from the outside web and US ogliopolistic companies such as Facebook and Twitter, through the implementation of its “Great Fire Wall”. Whilst on the one hand Westerners may view such measures as restrictive, perhaps there is a protective element to such actions that in retrospect, we too may have aspired to.

Discontinuity in global web use is often far less politically motivated and often evades our press. It may shock you to know that Google is not the search engine of choice in some of the world’s most technologically advanced nations. This reaslisation leads me to wonder how other cultures use the web, how can the web work better for them? is the web fit for purpose to move into frontier nations where literacy is far from universal and the concerns rather more fundamental than a 140-character regurgitation of our lunch can cater for?

Why would we want a cohesive global web anyway?

I believe that for the web to establish harmony and be “fit for purpose” as it expands and develops into a global phenomenon, it will have to become more representative of its diverse user base. It seems to me that there are a great deal of reasons why having a cohesive centrally governed (or at least cooperatively governed) web would benefit global society, examples include:

- Economic growth / stability

- Social & political stability

- A more diverse pool of ideas / talent for invention and innovation

- Increased collaboration across nations

- Increased tolerance of other cultures

- Improved security & safety

- Improved use as a tool to combat poverty

- Improved cross-cultural communication

However, the world has had a fractious history – is it therefore too much to hope that the web could transcend our propensity to be territorial and militant? What else might the web be destined for if it cannot sit comfortably within a global society?

The aim of my report will be to assess how two distinct disciplines would approach the feasibility of a "cohesive global web" and how they might come together to approach the problem from a multidisciplinary perspective. I have chosen the following disciplines for my review:

- Economics – primarily because I believe that Economics can be seen in a wealth of our current usage and the “cost benefit” argument seems to play a big role in whether we choose to collaborate / engage with a concept.

- Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology) – because I believe we will only make progress with the concept of a cohesive global web by moving away from our Anglo-centric view and observing the thoughts and experiences of other cultures.

Next steps…

My understanding of both fields is currently naïve at best, so I am excited to discover how the two fields will affect my perspective, and how they will come together to form a research methodology for looking at the future cohesiveness of the web. In the next week I will be compiling a to do list for the remainder of the semester and beginning to delve into my disciplines of choice.

Sources

Nytimes.com. 2013. Log In – The New York Times. [online] Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/14/business/international/google-jousts-with-south-koreas-piecemeal-internet-rules.html?_r=0 [Accessed: 23 Oct 2013]

The Verge. 2013. Cutting the cord: Brazil’s bold plan to combat the NSA. [online] Available at: http://www.theverge.com/2013/9/25/4769534/brazil-to-build-internet-cable-to-avoid-us-nsa-spying [Accessed: 23 Oct 2013]

Heine, J. 2013. Beyond the Brazil-U.S spat. [online] Available at: http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/beyond-the-brazilus-spat/article5186893.ece [Accessed: 23 Oct 2013]

Illustration: Gade, S. Retrieved from: http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/beyond-the-brazilus-spat/article5186893.ece

What is Anthropology? Part 1: Introduction no comments

Eriksen, T. H., 2004. What is Anthropology. London: Pluto Press.

Fieldwork

Although they “cast their net far and wide” (to provide context for observations), the work of the anthropologist is undertaken primarily through close interaction with individuals and the groups they live within. In-depth, structured interviews are used extensively and the key research method is ‘participant observation’ – the goal being to extensively record everyday experiences.

Concepts and theoretical approaches

Observation and reporting is influenced by the interplay between theories, concepts and methodologies.

Key concepts:

1. Language The human perception of the world is primarily shaped by language. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis proposes that language is a strong indicator of the world view that different groups inhabit. Studying the language structure (e.g. predominant use of grammar) can provide a good understanding of a particular groups’ everyday concerns.

2. Theories of the person

a) Egocentric. Person as a unique individual, whole and indivisible; responsible for the decisions they take.

b) Sociocentric. Person as a part of a community, who is a re-creation of an earlier human entity and has a pre-ordained role as a member of a social strata within the community (caste). A persons life is decided by fate and destiny (karma and dharma).

c) Ancestor-centric. Person as a unique individual with personal responsibility, but guided by ancestral spirits.

d) Relational. Person is primarily understood through their relationship with others.

e) Gender. The social construction of male/female distinctions, often described through the idiom of female oppression. Perception of oppression is based on personal appreciation. Male domination of formal economy is prevalent, with women exerting “considerable” informal power. Societies experiencing change often demonstrate conflict and tensions through gender and generational relations.

3) Theories of society

Often related to nation state. But each state contains communities, ethnic groups, interest groups, people who work or live together for a long time and have moral relationship. This presents a tension between ‘face-to-face’ society and abstract national society, where face-to-face societies have more permeable boundaries than state, and the state may be perceived as oppressive, corrupt, or remote.

a) Henry Maine (1861):

i) Status societies. Persons have fixed relationships to each other, based on birth, background, rank and position.

ii) Contract societies. Voluntary agreements between individuals, status based on personal achievement. Perceived as more complex than status societies.

b) Ferdinand Tönnies (1887):

i) Gemeinschaft (community). People belong to group with shared experiences and traditional obligations.

ii) Gesellschaft (society). Large-scale society. Driven by utilitarian logic, where the role of family and local community has been taken over by state and other powerful institutions.

These simple dichotomies are no longer followed by anthropologists as distinct boundaries within society are mutable. Power within a state may reside in political elite, but in ethnically plural states, the ethnic leadership may hold sway, or in poorly integrated states, local and kinship grouping may hold greater power than state politicians.

When setting out a study subject, anthropologists describe the scale of the subject (e.g. web use among teenagers in urban Europe).

4) Theories of culture

Possibly the most complex area in anthropology. The classic concept of culture is based on cultural relativism, which has been discredited due to its use to promote particular group claims, discriminate against minorities and promote aggressive nationalism. The key intellectual architect of apartheid was anthropologist, Werner Eiselen (Bantu Education Act, 1953).

a) No definition that all anthropologists agree on. A L Kroeber and Clyde Kluckholn (1952) – Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions describes and analyses 162 different definitions of culture.

The concept of ‘multicultural society’ indicates that culture has a different meaning to society – although there are similarities between them and are often used as synonyms for each other.

b) E B Tylor (1871). ‘Culture in its widest ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, customs, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society’.

c) Clifford Geertz (1960s). Interpretive Anthropology – shared meanings through public communications.

d) Objections to concept of culture:

i) Culture as plural can be seen as something that divides humanity, as the attention shifts from uniqueness of humanity to the differences between groups. (Boas – cultural relativism, Malinowski – field methodology, focus on single societies). Expressions of culture are unique and variable – but refer to universal, shared humanity.

ii) Problem of boundaries, internal variation and change. Delineating culture is problematic as there is considerable variation – often more so within groups than between groups.

iii) Mixed cultural forms and transnational flows of culture makes it more difficult to draw boundaries between cultures. Ulf Hannerz (1992) describes culture as flowing, dynamic process rather than static entity – culture as a global web of networks with no absolute boundaries, with nodes of varying density which are more or less stable.

iv) Inaccurate and vague nature of culture. Term used glibly to mean many different things and gives the illusion of insight. To understand what goes on in the world a more nuanced, specific concept is required.

5) Problems of translation

This includes translation of acts as well as language, and is mediated by necessary forms of compression and editing, which implies subjectivity. To understand a group it is not sufficient to simply observe, the anthropologist must learn the meaning and connotations of actions and words. Understanding only comes when a phenomenon is understood and explained in terms of its full meaning and significance to the group under observation – and how it forms part of a continuous whole. The main difficulty comes in translating abstract terms.

Problems: Misrepresentation, inevitable subjectivity of researcher, standard data organisation (gender, class, ethnicity) may not correspond to life-world of observed group.

Criteria for distinguishing good from bad subjectivity:

a) High level of detail.

b) Degree of context provided.

c) Triangulation with related studies.

d) Closeness of researcher to group (e.g. homeblindness).

6) Comparison

A means to clarify the significance of findings through contrasts that reveal similarities with other societies and build on theoretical generalisations. The aim of comparison is to understand the differences as well as the similarities.

a) Translation is a form of comparison – the native language is compared to the anthropologists own.

b) Establish contrasts and similarities between groups.

c) To investigate the possible existence of human universals (e.g. shared concepts of colour) – or to disprove them (e.g male aggression).

d) Quasi-experiment – anthropologists are unable to carry out blind studies, as the results would be inauthentic. Comparisons between two or several societies with many similarities, but with clear differences can provide an understanding of these differences.

7) Holism and context

Within anthropology holism refers to how phenomena are connected to each other and institutions to create an integrated whole, not necessarily of any lasting or permanent nature. It entails identification of internal connections in a system of interaction and communication.

a) Edmund Leach (1954) shows that societies are not in integrated equilibrium, but are unstable and changeable.

b) Fredrik Barth (1960s) transactionalism – a model of analysis which puts the individual at the centre and does not assume that social integration is a necessary outcome of interaction.

Holism has fallen from favour recently as anthropologists now understand that they are studying fragmented groups that are only loosely connected. However contextualisation may have become the key methodology; that is, every phenomenon must be understood within its dynamic relationship with other phenomena. The wider context is key to understanding single phenomena. For example – an anthropologist studying the Internet will explore both the online and offline lives of individuals. The choice of relevant contexts depends on the priorities of the researchers.

“Is it safe to drink the water?” no comments

How many people carry matches these days?/Susan Sermoneta ©2012/CC BY 2.0

Question

How can corporations be encouraged to open their data (so that we know it’s safe to drink the water)?

Background

The benefits to corporations of opening their data is well documented, but they are not necessarily appreciated in all sectors of industry.

Prospecting for oil and gas with the aim of engaging in hydraulic fracturing (‘fracking’) operations causes some popular concern which could be alleviated by the more open availability of real-time monitoring data.

In the UK, all industrial activities are subject to health and safety audits and some involve continuous, around the clock monitoring. For example Cuadrilla Resources employ Ground Gas Solutions to provide 24 hour monitoring of their explorations in the UK. Ground Gas Solutions monitoring aim to:

provide confidence to regulators, local communities and interested third parties that no environmental damage has occurred. (GGS, 2013)

Currently the data collected through this monitoring is made public via reports to regulation authorities, which can be subject to significant delay, are often written in technical language, and are not easily accessed by the general public.

My argument is that real time (or close to real time) monitoring data could be made open without any damage to the commercial advantage of the companies involved, and, if clearly and unambiguously presented (e.g. via a mobile app), could go some way to alleviating public concerns, particularly regarding the possible contamination of drinking water. Exploring what motivates some corporations to make their data open and the challenges they have overcome to do this, may suggest successful strategies for encouraging proactive, open behaviour within industry.

Disciplines

Anthropology – Considers key aspects of social life – identity, culture, rationality, ethnicity and belief systems.

Anthropologists aim to achieve a richness in the description of encounters they have with people and places, and have a strong tradition of creating narratives and developing theories that describe and attempt to explain human behaviour. In the context of the exploration industry, how might an anthropologist explore the underlying cultural values and prevalent beliefs of people working within corporations?

I believe that exploring this issue through the lens of anthropology would provide some insight into the workings of the energy exploration business and uncover useful data that may indicate strategies for encouraging corporations to share real time monitoring data.

Economics – Analyses the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

The widespread use of empirical data related to economic exchange together with emerging theories of human behaviour appear to underpin this discipline, which I believe have significant value to the study of my question. Exploring the commercial incentives for opening real time monitoring data from the perspective of differing economic theories combined with the data collection methodologies prevalent within this discipline can provide useful understandings of the question, which may point to practical solutions.

Anthropological Economics: an interdisciplinary approach

The question: “How can corporations be encouraged to open their data?” appears to call for solutions that tackle not simply the “bottom line” of economic necessity, but also the culture that requires individuals within corporations to maintain secrecy in order to maintain or improve their employers market position. From my current naive standpoint, a combination of the anthropologists qualitative, narrative-driven approach to studying human behaviour with the economists quantitative, theory-dominated view of commercial interaction looks like a worthwhile approach to gaining a better understanding of the key issues.

Proposed reading list

Anthropology:

Eriksen, T. H., 2004. What is Anthropology? London: Pluto Press.

Eriksen, T. H., 2001. Small Places, Large Issues: An Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology. London: Pluto Press.

Fife, W., 2005. Doing Fieldwork. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Miller, D. ed., 1995. Acknowledging Consumption. London: Routledge.

Economics:

Fogel, R. W., Fogel, E. M., Guglielmo, M. and Grotte, N., 2013. Political Arithmetic : Simon Kuznets and the Empirical Tradition in Economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Giudici, P. and Figini, S., 2009. Applied Data Mining for Business and Industry. London: Wiley.

Isaac, R. M. and Norton, D. A., 2011. Research in Experimental Economics: Experiments on Energy, The Environment, and Sustainability Governance in the Business Environment. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Quiggin, J., 2011. Zombie Economics: How Dead Ideas Still Walk Among Us. Woodstock: Princeton University Press.

The Digital Afterlife – What happens to our data when we die? no comments

As an undergraduate, I wrote my dissertation on the surrender of secrecy on social networking sites with a focus on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Through studying two age cohorts I discovered that young people, so called ‘digital natives’, often used their respective social networking profiles as a means to both establish and experiment with their emerging identities in different ways. On the other hand, older participants, aged between 45 and 50, took a very functional approach to social networking online.

Throughout my study all participants talked of uploading information like family photos, home movies and personal messages and achievements. However, not one participant talked about the future of their online profiles – no one seemed to realise, or be concerned by, the fact that they were moving their future heirlooms into more or less solely digital form through services like Facebook, YouTube and Gmail.

A rich chronicle of life is being created online and therefore I am interested in digital death and legacy. Do we have the right to be forgotten? Who now owns our memories? As, for the first time, users begin to pass away, who should have control over the data they leave behind, especially data that is so sentimental and personal?

So, I choose to look at this topic through the eyes of Law and Anthropology.

Law

Law, I believe, can provide insight into the rights of users and be progressive in determining new legislation for the future.

(Really I know nothing about Law so I hope to be more articulate with this soon…)

Anthropology

I’m anticipating an Anthropological approach to be entirely different to Law – I have briefly studied a little Anthropology in the past and believe that it’s field-based, subjective approach could provide some useful insight to how users might feel about the real and digital deaths of those they love. Similarly, they have their own digital death to consider… Should physical and digital death be synonymous?

To conclude, I hope to bright together a discipline I consider to be objective, Law (please correct me if I’m wrong!), with one that appears entirely subjective, Anthropology.

Initial Thoughts – Problem and Disciplines 1 comment

I am very interested in the issues of identity within the Semantic Web and Linked Data. Moving from a web of documents to a web of data with URIs (unique resource identifiers) for every referenced object/thing/person, aims to create new links between related content. However what happens when you want to refer to a person or thing which isn’t already referenced? This new object will be assigned a URI and others will then be able to link to it. However, who will manage this data and ensure it is correct? This issue is especially significant when referring to an individual. If someone has no intention of creating an online presence or doesn’t have access to the World Wide Web, what impact will this URI about them have on their life? They might not even be aware that a whole series of connected data about them is being collated on the web for everyone else to access. I am going to look at this area from the point of view of philosophy and either sociology or anthropology.

I have started my research by looking into the recognised strands of each of these disciplines.

Philosophy contains a number of interesting areas which could be applied to this problem. Philosophy of language could look at how the use of language could affect the formation of an online network and linked data, (http://www.philosophy-index.com/philosophy/language/). The political angle of philosophy would be interested in government, law and social justice, (http://www.philosophy-index.com/philosophy/political/). But possibly the most interesting angle would be to look at the philosophy of the mind, specifically the mind body problem (http://www.philosophy-index.com/philosophy/mind/mind-body.php). This train of thought would look at the idea of mind and body being separate and a philosopher could argue that each should have their own URI?

Secondly I want to look at the idea of URIs and identity in relation to cultures and at the societal impact that online identity could have. Sociology could include the social organisation or social change (http://savior.hubpages.com/hub/Areas-of-Sociology).

Similarly to Philosophy, Anthropology could include the study of language, and how this could impact the online community. Linguistic Anthropology looks at the cultural impact on nonverbal communication (http://anthro.palomar.edu/intro/fields.htm). Cultural Anthropology:

“All of the completely isolated societies of the past have long since been drawn into the global economy and heavily influenced by the dominant cultures of the large nations. As a consequence, it is likely that 3/4 of the languages in the world today will become extinct as spoken languages by the end of the 21st century. Many other cultural traditions will be lost as well. Cultural and linguistic anthropologists have worked diligently to study and understand this diversity that is being lost.” (http://anthro.palomar.edu/intro/fields.htm).

This field might look more negatively upon the web, as a tool which is potentially destroying the traditions and cultural diversity, which makes the world so varied.

This is a very brief introduction to the problem and fields which I wish to investigate.

Management Models no comments

Last week I wrote about an introduction to the basic concepts and perspectives in the discipline of management promising a review of some management models this week. This is a summary of Boddy’s second chapter ‘Models of Management’.

Boddy defines a model as aiming to ‘identify the main variables in a situation, and the relationships between them: the more accurately they do so, the more accurate they are.’ A model furthermore provides a ‘mental toolkit to deal consciously with a situation’. Boddy emphasise that managers can draw upon different models according to the varied situations they face – what is important is understanding the values embodied in the model or theory and act accordingly. That is also known as thinking critically about a situation, an essential skill in management.

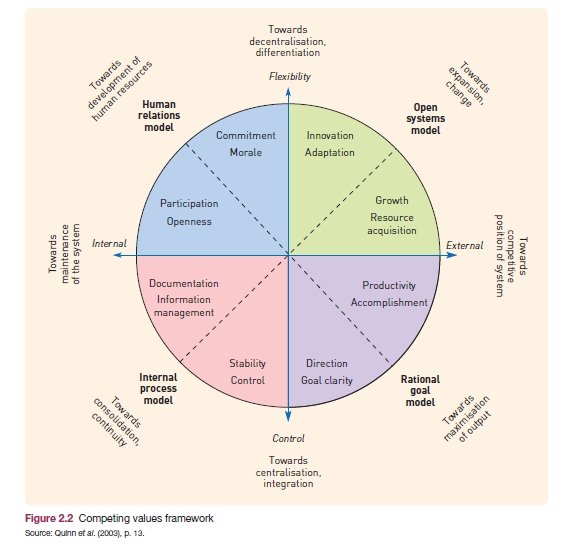

Boddy and others identify four key types of models of management according to their underlying philosophies:

- rational goal

- internal process

- human relations

- open systems

Rational goal models

Some of the first kinds of models to have been developed, their origins are found in the formation of the modern firm, during the Industrial Revolution, where managers were face with the need to manage new organisational structure profitably. It evolved from the tradition of scientific management and operational research. The model emphasise the aim of maximising output/profit through enhanced control and quantitative information as a basis for decision-making.

Internal process models

These come from the Weberian bureaucratic management ideas and from Henri Fayol’s notion of ‘administrative management’ which emphasise rules and regulations over personal preferences, division of labour and hierarchical structure. While the concept of bureaucracy has been widely criticised (notably for stifling creativity) it has been supported when it allows employees to master their tasks therefore enhancing security and stability and is still widely used today, notably in the public sector.

Human relations models

These theories were developed when experiments on working conditions (lighting or other material factors) produced unexpected results. It was shown that altering the environment positively or negatively, output from the experimental team still increased. Elton Mayo, invited to comment on the results, asserted that output growth was the result of the new social relations established in the team. Individuals felt special, they were asked for their opinion, and as part of the experiment fully collaborated with one another. This led theorists to emphasise the importance of social processes at work, including the well-being of employees.

Open systems

Finally open systems models where the organisation is seen ‘not as a system but as an open system’, which interacts with its environment. Resources are imported, undergo transformations and turned into output that generate profit. Information about the performance of the system goes back as a feedback loop into the inputs. Important variants include socio-technical systems where outcome depends on the interaction of technical and social subsystems. Another is the notion of contingency management which emphasises the need for adaptability to the external environment. And finally complexity theory which focuses on the complex systems, their dynamics and feedback loops where agents within the system interact autonomously through emergent rules. These emphasise the non-linearity of change in organisations.

The table below provides a summary of the four models (from Boddy 2010, p. 61).

In fact management theorists Quinn et. al. (2003) believe that the four successive models of managements complement rather than contradict each other, and they provide a framework that integrates these various model – the ‘competing values framework

Next week I will look to read about management and global issues to get a better grasp of the discipline’s approach to an issue that transcends its main ontological actor – the organisation.

References

Boddy D. (2010) Management: An Introduction, 5th edition, Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall

Quinn, R.E., Faerman, S.R., Thompson, M.P. amd McGrath, M.R. (2003) Becoming a Master Manager: A Competency Framework, 3rd ed., Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons