Ethnography 3 – Methodologies & Analysis no comments

Researcher: Jo Munson

Title: Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?

Disciplines: Economics, Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

How one modern Ethnographer uses technology to perform fieldwork.

Methodologies in Ethnography

The primary method of collecting data and information about human cultures in Ethnography is through fieldwork, although comparison of different cultures and reflecting on historical data is also important in Ethnographic methodology. The majority of Ethnographic research is qualitative in nature, reflecting its position as a social science. Ethnographers do however make attempts to collect quantitative data, particularly when trying to take a census of a community and in comparative studies.

The methods used to collect information can be broadly categorised as follows:

Fieldwork methods:

- Observation, Participant Observation & Participation – a feature of nearly all fieldwork, Observation can vary from a high level recording of events without interacting with the community to becoming wholly immersed in the community. The latter can take months or even years and will usually require the Ethnographer to learn the language of, and build relationships with the locals.

- Survey & Interview – surveys can be structured with fixed questions (often used at the start of a fieldwork placement), or unstructured, giving the interviewee an opportunity to guide the direction of his or her answers.

Comparative methods:

- Ethnohistory – Ethnohistory involves studying historical Ethnographic writings and ethnographic or archaeological data to draw conclusions about an historic culture. The field is distinct from History in that the Ethnohistorian seeks to recreate the cultural situation from the perspective of those members of the community (takes an Emic approach).

Unlike Observation / Participation and Survey, Ethnohistory need not be done “in the field”. Ethnohistory has become increasingly important as it can give valuable insight in to the speed and form of the “evolution” of societies over time. - Cross-cultural Comparison – Cross-cultural Comparison involves the application of statistics to data collected about more than one culture or cultural variable. The major limitations of Cross-cultural Comparison are that it is ahistoric (assumes that a culture does not change over time) and that it relies on some subjective classifications of the data to be analysed by the Ethnographer.

Sources of bias

The sources of bias in Ethnographic data collection can be substantial and often unavoidable, some of the most common are:

- Skewed (non-representative) sampling – samples can be skewed for many reasons. Sample sizes are often small, so the selection of any one interviewee may not be representative of the population. The Ethnographer can also only be in one place and will often make generalisations about the whole community based on the small section he or she interacts with. The Ethnographer is also limited to the snapshot in time that he or she observes the community.

- Theoretical biases – the method of stating a hypothesis prior to investigation may cause the Ethnographer to only collect data consistent with their viewpoint relative to the initial hypothesis.

- Personal biases – whilst Ethnographers are acutely aware of the effect their own upbringing may have on their objectivity (think Relativism), this awareness does not stop prior beliefs having an effect on data collection.

- Ethical considerations – Ethnographers may uncover information that could compromise the cultural integrity of the community being observed and may choose to play this down to protect their informants.

Interpreting Ethnographic research findings

Whilst there is no consensus on evaluation standards in Ethnography, Laurel Richardson has proposed five criteria that could be used to evaluate the contribution of Ethnographic findings:

-

Substantive Contribution: “Does the piece contribute to our understanding of social-life?”

Aesthetic Merit: “Does this piece succeed aesthetically?”

Reflexivity: “How did the author come to write this text…Is there adequate self-awareness and self-exposure for the reader to make judgments about the point of view?”

Impact: “Does this affect me? Emotionally? Intellectually?” Does it move me?

Expresses a Reality: “Does it seem ‘true’—a credible account of a cultural, social, individual, or communal sense of the ‘real’?”

These reflections, alongside the statistical output of quantitative or Cross-cultural Comparative study can be used to reform Ethnographic theories and gain insight into human culture.

Next time (and beyond)…

The order/form of these may alter, but broadly, I will be covering the following in the proceeding weeks:

Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?Ethnography 1 – Introduction & DefinitionEthnography 2 – Disciplinary ApproachEconomics 1 – Introduction & DefinitionEconomics 2 – Disciplinary Approach, the Big TheoriesEthnography 3 – Methodologies & Analysis- Economics 3 – Modelling & Methodologies

- Ethnographic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Ethno-Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

Sources

The American Society for Ethnohistory. 2013. Frequently Asked Questions. [online] Available at: http://www.ethnohistory.org/frequently-asked-questions/ [Accessed: 31 Oct 2013].

Umanitoba.ca. 2013. Objectivity in Ethnography. [online] Available at: http://www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts/anthropology/courses/122/module1/objectivity.html [Accessed: 31 Oct 2013].

Peoples, J. and Bailey, G. 1997. Humanity. Belmont, CA: West/Wadsworth.

Richardson, L. 2000. Evaluating Ethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 6 (2), pp. 253-255. Available from: doi: 10.1177/107780040000600207 [Accessed: 31 Oct 2013].

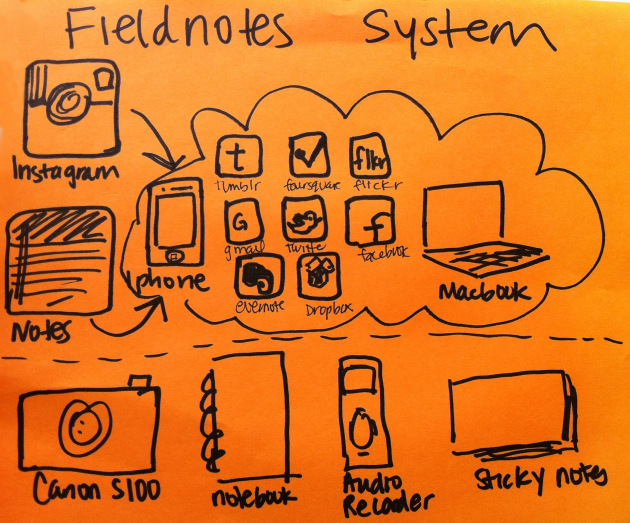

Image retrieved from: http://ethnographymatters.net/tag/instagram/