Sound Heritage returns

Just before the spring break, the Sound Heritage network met up for its second study day on music research and interpretation in country houses. Instead of gathering in the university, we made a field trip out to Chawton, home of Chawton House Library and Jane Austen’s House Museum. We had a fantastic welcome from our partners at Chawton House, and even the weather helped out – providing a day of mild spring sunshine that created an almost ridiculously perfect chocolate-box experience, complete with daffodils and fluffy sheep.

The day began with a fascinating presentation by historical keyboard specialist Ben Marks, Keeper of the Benton Fletcher collection at Fenton House, who regularly advises on other National Trust properties as well as for many other houses in the public and private sectors. He gave a brilliant overview of issues affecting the conservation, restoration and use of historical instruments in heritage contexts. Instruments may be present as part of an ensemble of furniture and decoration, as for example at Kedleston, where pianos with provenance to the house form part of the display.

Alternatively, instruments may reflect collection according to musical or

organological concerns – as at Hatchlands, which houses the Cobbe collection of composer-related instruments. Instruments may be found restored or unrestored in each of these contexts, and the display may be decorative or interactive. Each of these contexts and modes of display raises different issues. Restoration may destroy original features of a historic instrument, and overuse may cause irreversible damage. At the same time, restoration and interactive display can provide valuable educational opportunities and enhance visitor experience in many ways. Ben provided guidelines to help the decision-making process and achieve a balance between competing needs. Where instruments are rare and in original condition, they should be left unrestored, de-tensioned to aid long-term conservation. Where instruments have been restored and are useable, a programme of regular maintenance (including programmed periods of rest) should be put in place, with all interventions carefully documented so that effects on the instrument may be tracked. Players should be issued with guidelines and use should be monitored (both to prevent accidental damage, and to keep track of hours of use). Ben walked us through the procedures in place at Fenton House, which has a highly developed and well-tested programme of conservation and maintenance for instruments maintained in playing condition.

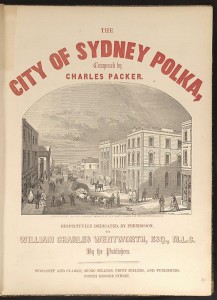

From questions of conservation we moved to opportunities for interpretation. Our international partner Dr Matthew Stephens from Sydney Living Museums gave us a tour of the innovative ways music is featuring in the interpretation of historic houses in SLM’s portfolio. I was particularly inspired by the creative takes on the Dowling Songbook, aka the “Rosetta Stone of early Australian music making,” which is held at Rouse Hill House. This book was made in the 1830s for a young Sydney couple whose lives were a source of constant gossip after a scandalous court case in 1832 (for more on this, see Matt Tyler Jone’s blog over here). An item from the songbook features with other sheet music in SLM’s Threads of Connection project, which uses series of ten related objects (watches, jewellery, trophies, etc) to tell a broader story. I also loved the “The Art of Playing Polka” on the SLM’s Vaucluse House site, which includes the digitised sheet music and a recording of “The City of Sydney Polka” made at Vaucluse House along with information about its connection to the house and the wider context of social dancing. Vaucluse House is also the site of a new film, “Sweet Noise: Making Music at Vaucluse House,” which traces the history of music in the house and follows the restoration of its Collard and Collard grand piano.

We arrived at Chawton House as they were putting the finishing touches on their wonderful exhibition commemorating the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s Emma, and the Austen connection provided a further theme for the day. We toured Jane Austen’s House Museum at lunchtime and then returned to Chawton House for a presentation on the recently released digital facsimile of the Austen family music books, a collaborative project between the Music department, the University of Southampton’s Hartley Library digitisation unit, and the owners of the books (which include the Museum as well as private owners descending from the Austen family). I provided a quick overview of the digitisation project before handing over to Samantha Carrasco, whose 2013 Southampton PhD examined the Austen books in the context of Hampshire county music culture. Sam provided a series of snapshots from the books – illustrated on the historic piano in the Chawton House dining room – to suggest the potential for using repertoire from the Austen collection in heritage interpretation.

After afternoon workshops on some of the network’s research and interpretation projects, we finished the day with a performance programme curated by harpsichordist Dr Vivian Montgomery of Longy School (Massachusetts). Participants had sent in little known pieces featuring connections to country houses, and several network members collaborated with Vivian to present them in a kind of Antique Roadshow of country house curiosities.

The activity gave us several particularly good opportunities to pick up threads from the earlier presentations. For example, Katrina Faulds played a waltz from the Bresslauer Favorit Redout-Deutsche Tänze, a collection that Lydia Acland purchased in Vienna in 1815 and brought back to her country estate at Killerton (Devon). This piece also appears in the Austen family collection as “The Queen of Prussia’s Waltz” – offering different interpretative narratives, from the Aclands’ personal experiences at the Congress of Vienna to the broader movement of music across continents and levels of society. There were also Austen connections to Scottish music collected in the eighteenth century and now in the collections at Boughton House: Dr David

McGuinness (University of Glasgow) performed Domenico Corri’s variations on the Lea Rig, edited by Nathaniel Gow – a tune also known as “My ain kind dearie” (words to the refrain of a song by Burns to this tune) under which title the same variations appear in Jane Austen’s personal keyboard manuscript. Some of this music – in dance band arrangements like those that would have been used at country house balls – appears on David’s recent CD, Nathaniel Gow’s Dance Band – Fiddle music from Scottish printed sources 1761-1823 by Concerto Caledonia.

The Dowling songbook provided us with “The Angel’s Whisper” – performed at Chawton by Kate Hawnt, accompanied by Vivian. This was written and composed by Samuel Lover and published in London c.1835. “Grosse’s Instructions in singing” was bound together with the Dowling’s sheet music, and annotations suggest it may have been used to ornament some of the songs. Flinton, the Dowling home, has been demolished but this well-documented music collection offers a rare opportunity for other surviving Sydney houses from the same period, such as Elizabeth Bay House (1839), where there is little evidence of the family’s musical repertoire.

Vivian included a piece from her recent CD, Brilliant Variations on Sentimental Songs, that showed how the English domestic repertoire travelled abroad during the 19th century. James Bellak’s The Last Rose of Summer: Impromtu (sic) Brillant (sic) for the Piano (Philadelphia: Lee & Walker, 1852) draws upon the wildly popular song from volume 5 of Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodies.

The entire performance was informative and entertaining but also informal, and I thought it worked well as an alternative to the standard concert format, which often doesn’t work for this kind of repertory or setting. For our the network’s next meeting at Tatton Park in November, we are hoping to include another concert alternative – watch this space . . .