Criminology – Thinking about some basics no comments

It’s admittedly been a while since my last post, but I have still been a bit scattered about the nature of my topic and have been earnestly trying to refrain from focussing on Web Science issues that are too narrow and specifically, archaeological. In lieu of this I’ve been focused on getting to grips with Criminology first, a discipline which I know I want to study and apply elsewhere. I’ve been taking lots of notes along the way, but hadn’t yet transcribed them here, so here goes..

The following mostly stems from Walklate 2005: Criminology: The Basics.

What is Criminology?

Criminology as Multidisciplinary

One of the big take home points for me about Criminology as a discipline is actually how inherently multidisciplinary it is. Depending on who you ask, you might get a somewhat different take on the nature of criminological study, typically framed by the ‘other discipline’ from which the researcher stems from. This includes criminology from an economics, history, psychology, law, sociology, anthropology, and philosophical multidisciplinary stance – all researching and defining criminology somewhat differently. Yet Walklate claims all disciplines are “held together by one substantive concern: CRIME.”

What is Crime?

The question of “what is crime” within the criminology community is contested, and seems to go beyond defining crime as simply breaking the law though this is a useful starting place for most researchers, as it removes the emotive nature of studying such a subject area. But criminologists must also consider that laws change, thus understanding the processes of criminalizing and decriminalizing and the processes that influence policy can also fall under the remit of criminology. Criminologists must also consider social agreement, social consensus and societal response to crime, which extends the crime definition beyond that which is simply against the law. In addition, crime still occurs regardless of the content of the law – and this falls within a sub sect described as “deviant behaviour” which seems to lend itself more to the psychological-criminological studies.

Sociology of Crime

The sociology of crime is concerned with the social structures that lead to crime – “individual behaviour is not constructed in a vacuum” – and it takes place within a particular social and cultural context that must be examined when looking addressing criminal studies. Social expectations and power structures surrounding criminal acts are also important to the nature of studying crime in society.

Example applications and questions

- Why does there seem to be more of a certain type of crime in some societies and not others?

- Why/If the occurrence of a type of crime is changing throughout time?

- Why do societies at times focus efforts on reducing/managing/effecting certain types of crimes?

feminism – forced a thinking about the “maleness of the crime problem”, and question of masculinity within society – “search for transcendence” (to be master and in control of nature)

Counting Crime

Sources for analyzing crime

- direct experiences of crime

- mediated experiences of crime

- official statistics on crime – Criminal Statistics in England and Wales, published yearly a good starting point. Home Office, FBI, EuroStat

- research findings of criminologists

“the dark figure of crime” – the criminal events only known to the offender and the victim – e.g. those that don’t get caught, or not reported/recorded.

Not all recorded offenses have an identifiable offender/not all offenders are convicted – partiality

The 3 R’s: recognising, reporting, recording.

Reporting – criminologists must understand reporting behaviour and reasons for not reporting crime, and then how that effects the results/statistics upon analysis.

- behaviour may be unlawful but witnesses may not recognise it as such, thus not report it

- witnesses may recognise an act as criminal but consider it not serious enough to report

- judicial process – and numbers of tried vs convicted, the politics of this and its subsequent effects in reporting

- police discretion on recording crime – e.g. meeting and reporting to targets

identifying trends – it’s important to understand crime statistics over time

- understand whether crime and terms for crime change over time, changes to how an offense is defined

- criminal victimisation surveys – do these exist for Internet fraud

- crimes against the personal vs crimes against property

the Problem of Respondents – getting people to respond to surveys can be challenging.

- big difference between crimes known to police and the dark figure of crime

- big difference between crimes made visible by criminal victimisation surveys and those that remain invisible (e.g. tax fraud)

Web Doomsday: Northeast Blackout Case Study no comments

10 years ago, on 14th August 2003, a combination of minor faults on power infrastructure led to a huge power outage that left over 55 million people in North America without power for as long as four days. In this post, I will give an overview of how people reacted and the long-term impact of the event. In particular, I will consider how the loss of power is analogous to the loss of the web as a convenience, a luxury, and as a life-supporting mechanism. By making these connections, we should be able to get a better understanding of the anthropological and economic issues at hand, as these are very pertinent to how society has used both electricity and the web in human and economic development.

Donald was one person who experienced four days of the blackout. He told his story, detailing the troubles with living without electricity for four days. He lived in Detroit and was at work when the power went out. Donald couldn’t continue work, nor could he make phone calls, because the networks were unavailable. The drive home was dangerous because there were no traffic lights. Donald had very little food reserves, nor any way to cook. He was not at all prepared for loosing a resource that he had not considered would simply stop. He had to make plans to leave and had to prepare for looting:

With only the couple snacks we had left, I knew Monday we had to get somewhere west of Brighton. We simply didn’t have any food left. I heard a story about a lot of looting on the news, but that story didn’t repeat. It must have been true. My Beretta 9mm was dutifully holstered to my hip at that point.

Donald Alley – http://www.examiner.com/article/remembering-the-northeast-blackout-of-2003-ten-years-later

Donald’s experience echoed the experiences of millions. The initial nonchalant reaction of “oh, it’s just a power cut” gradually became a sense for survival: the urgent need for basic sustenance – food, water, shelter. The initial reaction of “great, a day off work” was undermined by the following few days of an inability to work, with estimates putting the economic cost between $7 and $10 billion [1].

Times Square during the Northeast blackout of 2003

Would loosing web would result in such extreme consequences?

Survival-motivated crimes, such as looting, are a result of loss of basic needs. Could loosing the web for an extended period of time foster this kind of reaction? If we consider the UK alone, approximately 87% of the population are internet users. In fact, almost all people aged 16-44 have used the internet. It’s pervasively used and we depend on it for communication, reading the news, and even for delivering us life-saving information. The web has been considered a tool for promoting freedom of expression and it might further be considered that internet access itself is a human right. The web might not have existed long enough to provoke rioting at it’s disappearance, but our dependency upon it would certainly lead to public disquiet.

And in terms of the economy, vast amounts of business has been transferred onto the web. It is by design easier and more efficient to work on the web, where data is easy to share and collaborate on. Many people could not work during the blackout because their work is based online. If the web were to disappear, we would face a similar economic disruption: work could not take place because current business infrastructures require the web to work. The economy has been affected by the web since it’s earliest days, when we experienced huge investment in the internet sector leading to the dot-com bubble, which then burst, leading to the failure of many technology companies (for example, Cisco’s stock declined by 86%).

The availability of electricity and the web are intrinsicly related issues in terms of the influence they have on society and the economy. From large-scale power outages, we can gain some insight into what the consequences of a web doomsday might be. We might not yet be aware of our dependency on the web, just as Donald was not aware of his dependency on electricity to give him his basic needs. This raises some interesting questions. Should we work to gain a better understanding of what we use the web for and how we are dependant on it, and from this, ensure that we can sustain ourselves without access? And in terms of the economy, should businesses be prepared for the loss of the web, so as to not lead to economic disaster in such a case?

In the next post, I will discuss how censorship in some countries (specifically the great firewall of china) is analogous to the lack of web availability. In this, I will consider how people have reacted and what the long-term effects have been.

[1] ICF Consulting, “The Economic Cost of the Blackout: An Issue Paper on the Northeastern Blackout, August 14, 2003.”

Ethnography 3 – Methodologies & Analysis no comments

Researcher: Jo Munson

Title: Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?

Disciplines: Economics, Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

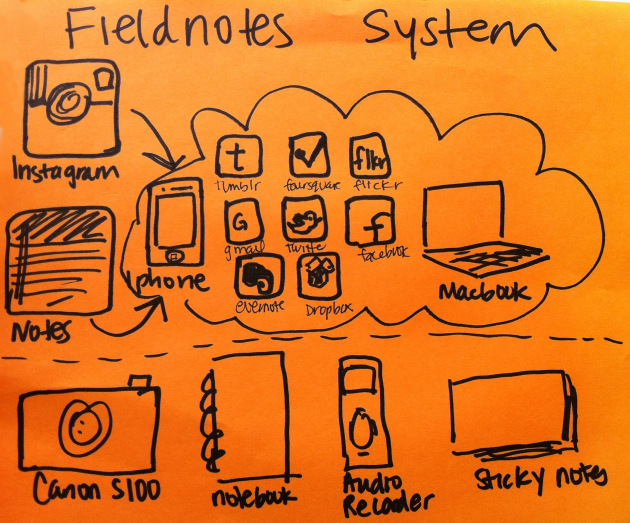

How one modern Ethnographer uses technology to perform fieldwork.

Methodologies in Ethnography

The primary method of collecting data and information about human cultures in Ethnography is through fieldwork, although comparison of different cultures and reflecting on historical data is also important in Ethnographic methodology. The majority of Ethnographic research is qualitative in nature, reflecting its position as a social science. Ethnographers do however make attempts to collect quantitative data, particularly when trying to take a census of a community and in comparative studies.

The methods used to collect information can be broadly categorised as follows:

Fieldwork methods:

- Observation, Participant Observation & Participation – a feature of nearly all fieldwork, Observation can vary from a high level recording of events without interacting with the community to becoming wholly immersed in the community. The latter can take months or even years and will usually require the Ethnographer to learn the language of, and build relationships with the locals.

- Survey & Interview – surveys can be structured with fixed questions (often used at the start of a fieldwork placement), or unstructured, giving the interviewee an opportunity to guide the direction of his or her answers.

Comparative methods:

- Ethnohistory – Ethnohistory involves studying historical Ethnographic writings and ethnographic or archaeological data to draw conclusions about an historic culture. The field is distinct from History in that the Ethnohistorian seeks to recreate the cultural situation from the perspective of those members of the community (takes an Emic approach).

Unlike Observation / Participation and Survey, Ethnohistory need not be done “in the field”. Ethnohistory has become increasingly important as it can give valuable insight in to the speed and form of the “evolution” of societies over time. - Cross-cultural Comparison – Cross-cultural Comparison involves the application of statistics to data collected about more than one culture or cultural variable. The major limitations of Cross-cultural Comparison are that it is ahistoric (assumes that a culture does not change over time) and that it relies on some subjective classifications of the data to be analysed by the Ethnographer.

Sources of bias

The sources of bias in Ethnographic data collection can be substantial and often unavoidable, some of the most common are:

- Skewed (non-representative) sampling – samples can be skewed for many reasons. Sample sizes are often small, so the selection of any one interviewee may not be representative of the population. The Ethnographer can also only be in one place and will often make generalisations about the whole community based on the small section he or she interacts with. The Ethnographer is also limited to the snapshot in time that he or she observes the community.

- Theoretical biases – the method of stating a hypothesis prior to investigation may cause the Ethnographer to only collect data consistent with their viewpoint relative to the initial hypothesis.

- Personal biases – whilst Ethnographers are acutely aware of the effect their own upbringing may have on their objectivity (think Relativism), this awareness does not stop prior beliefs having an effect on data collection.

- Ethical considerations – Ethnographers may uncover information that could compromise the cultural integrity of the community being observed and may choose to play this down to protect their informants.

Interpreting Ethnographic research findings

Whilst there is no consensus on evaluation standards in Ethnography, Laurel Richardson has proposed five criteria that could be used to evaluate the contribution of Ethnographic findings:

-

Substantive Contribution: “Does the piece contribute to our understanding of social-life?”

Aesthetic Merit: “Does this piece succeed aesthetically?”

Reflexivity: “How did the author come to write this text…Is there adequate self-awareness and self-exposure for the reader to make judgments about the point of view?”

Impact: “Does this affect me? Emotionally? Intellectually?” Does it move me?

Expresses a Reality: “Does it seem ‘true’—a credible account of a cultural, social, individual, or communal sense of the ‘real’?”

These reflections, alongside the statistical output of quantitative or Cross-cultural Comparative study can be used to reform Ethnographic theories and gain insight into human culture.

Next time (and beyond)…

The order/form of these may alter, but broadly, I will be covering the following in the proceeding weeks:

Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?Ethnography 1 – Introduction & DefinitionEthnography 2 – Disciplinary ApproachEconomics 1 – Introduction & DefinitionEconomics 2 – Disciplinary Approach, the Big TheoriesEthnography 3 – Methodologies & Analysis- Economics 3 – Modelling & Methodologies

- Ethnographic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Ethno-Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

Sources

The American Society for Ethnohistory. 2013. Frequently Asked Questions. [online] Available at: http://www.ethnohistory.org/frequently-asked-questions/ [Accessed: 31 Oct 2013].

Umanitoba.ca. 2013. Objectivity in Ethnography. [online] Available at: http://www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts/anthropology/courses/122/module1/objectivity.html [Accessed: 31 Oct 2013].

Peoples, J. and Bailey, G. 1997. Humanity. Belmont, CA: West/Wadsworth.

Richardson, L. 2000. Evaluating Ethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 6 (2), pp. 253-255. Available from: doi: 10.1177/107780040000600207 [Accessed: 31 Oct 2013].

Image retrieved from: http://ethnographymatters.net/tag/instagram/

Economy and Open Source no comments

We could define Economy as an infrastructure of connections among producers, distributors, and consumers of goods and services in one community. On the other hand, we could state that the Internet is a global network that connects public and private sectors in different ecosystems : industry, academia and government.

There is no doubt about the potential of Internet in the economy of a country because it can minimize the transaction cost of goods and services, creating efficient and productive distribution channels, developing clusters of specific areas, increasing supply and demand and providing more consumer choices.

For this reason, technology plays a crucial role for the decision making process because it helps us to create strategies and to develop solutions. In the last two decades proprietary or closed source software dominated the industry, causing high costs derived of licenses and patent use, restricting users to modify, redistribute or share their products. Furthermore, the use of reverse engineering in private software result in a penalty or even jail, inhibiting innovation and software development.

Nowadays, public and private sectors in any domain provide the opportunity to use open source software as an alternative in order to increase security, reduce costs, improve quality, develop interoperability, customization, but mainly to uphold independence and freedom.

Some people think that open source software is not a real choice because there is not technical or financial support; however, in these essays we will study the open source phenomena and their implications in the global economy.

First, let start by defining the term open source:

According to the Open Source Initiative, (1):

“Open source doesn’t just mean access to the source code. The distribution terms of open-source software must comply with the following criteria:

1.-Free distribution

2.-Source code

3.-Derived works

4.-Integrity of the author´s source code

5.- No discrimination against persons or groups

6.- No discrimination against fields of endeavor

7.-Distribution of licenses

8.-License must not be specific to a product

9.-License must not restrict other software

10.-License must be technology neutral

In the same way the Open Source Paradigm (2) explains that:

In an ecosystem composed by academic institutions, companies and individuals that come to the idea to solve a specific need through software development. Mostly, the initial project is done by just one entity and subsequently is released to the community in order to share and to continue the development or the knowledge. If the software is useful, others members make use of it and just when the algorithm is solved by the software development and it is useful to others the circle of Open Source paradigm is completed.

A good example of the use of Open Source Paradigm is the Apache Web Server because it had been built by a group of people who needed to solve the their web server problems. This group were kept in touch by email and they worked separately, but they were determined to work together and coordinately and finally their first release were in April 1995.

Furthermore, the Open Source paradigm promotes paramount economic benefits. For instance, Open Source allows better resources allocation, it can dispense the risk and cost related to projects and it gives the control to users allowing them to customize it according to their needs.

In summary, we can say that, Open source encourages people to work together toward a specific goal and the desire to create solution, promoting innovation and software development.

References:

1.-Open Source Initiative [n.d.] Open Source Initiative [online]

Available from: http://opensource.org/osd [Accessed 05 November 2013]

2.-Bruce Perens (2005) The Emerging Economic Paradigm of Open Source [online] George Washington University. Available from: http://perens.com/works/articles/Economic.html [Accessed 12 November 2013]

What to study in Computer Science? no comments

After looking for a reasonable definition of Computer Science and whether it can be considered a discipline last week, I wanted to focus on the different approaches to study the field this week. Initially I tried to do this with the help of an introductory book to Computer Science: Computer Science. An overview by Brookshear. I found that Brookshear explains more the different aspects of computers that can be studied. Therefore, I also looked at two other texts. Still, approaches in Computer Science do not seem as commonly separated as in Psychology. However, in the end of this post I will look at some approaches.

Brookshear starts in his book with explaining that algorithms are the most fundamental aspect of Computer Science. He defines an algorithm as “a set of steps that defines how a task is performed.” Algorithms are represented in a program. Creating these programs, is called programming (Brookshear, 2007: p. 18). Brookshear explains later in his book that “programs for modern computers consist of sequences of instructions that are encoded as numeric digits (Brookshear, 2007: p. 268).

Fundamental knowledge to understanding problems in Computer Science is to see how data is stored in computers. Computers store data as 0s and 1s, which are called bits. The first represents false, while the latter represents true. According to Brookshear, this true/false values are named Boolean operations (Brookshear, 2007: p. 36). Computers do not just store data, they also manipulate it. The circuitry in the computer that does this, is called the central processing unit (Brookshear, 2007: p. 96). Next to manipulating, data can also be transferred from machine to machine. If computers are connected in that manner, networks, this can happen (Brookshear, 2007: p. 164). The Internet is a famous example of an enormous global network of interconnected computers.

Computer Science has several subfields that are seen as separate studies. An example of this is software engineering. Brookshear claims that it “is the branch of computer science that seeks principles to guide development of large, complex software systems”(Brookshear, 2007: p. 328). Another example is Artificial Intelligence (AI). Brookshear explains that the field of AI tries to build autonomous machines that can execute complex tasks, without the intervention of a human being. These machines therefore have to “perceive and reason” (Brookshear, 2007: p. 452).

Tedre gives a couple of examples of other subfields in Computer Science, but does not say that those subfields are the only or even most important ones. He sums up complexity theory, usability, the psychology of programming, management information systems, virtual reality and architectural design. Tedre argues that there should be an overarching set of rules for research in these fields. However, later he also argues that computer scientists often need to use approaches and methods from different fields, because this is the only way in which they can deal with the amount of topics in Computer Science (Tedre, 2007: p. 107, 108). Computer scientists thus seem to deal with the difficult task of incorporating many different fields, but at the same time they need to learn how to use a similar set of rules to study these fields.

Denning et al. define the most clear set of subfields in Computer Science: algorithms and data structures, programming languages, architecture, numerical and symbolic computation, operating systems, software methodology and engineering, databases and information retrieval, artificial intelligence and robotics, and finally human-computer communication. They justify their selection, because every one of those subfields has “an underlying unity of subject matter, a substantial theoretical component, significant abstractions, and substantial design and implementation issues” (Denning et al., 1989: p. 16, 17).

Tedre argues, based upon the research of Denning et al., that there have been three ‘lucid’ traditions in Computer Science: the theoretical tradition, empirical tradition and engineering tradition. He argues that because of the adoption of these different traditions, the discipline of Computer Science might have ontological, epistemological and methodological confusion (Tedre, 2007: p. 107).

I can conclusively argue that it is not easy to present a concise image of Computer Science. After having difficulties last week in finding one proper definition for Computer Science, this week I had problems in finding comprehensive ways in which Computer Science is studied. Next time, I will look at how Psychology and Computer Science can be used to study online surveillance. Later, I will also look how the two disciplines overlap.

Sources

Brookshear, J. Glenn. Computer Science. An Overview. Ninth Edition. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2007.

Denning, P. et al. “Computing as a discipline”. Communications of the ACM 32(1), 1989: p. 9-23.

Tedre, Matti. “Know Your Discipline: Teaching the Philosophy of Computer Science”. Journal of Information Technology Education 6(1), 2007: p. 105-122.

Web Doomsday: How Realistic Is It? no comments

Despite our modern-day dependency on services offered through the web, few of us have given thought into what the consequences to us would be if the web were to disappear. It might simply seem unlikely, and not worth planning for. However, there are many potential causes, intentional or not, for widespread loss of access to the web. I will outline some of these in this post and will argue that it is realistic and that we as a society should be prepared.

The size of the technical infrastructure required to deliver the web to our fingertips is huge. The larger a system, the more points of failure. Because the system is stretched over a large geographic area, where there are climate extremes, natural disaster is a large risk. Storms, earthquakes and erosion can easily break vital equipment. Such a large system also lead to scope for technical failures. The Northeast United States blackout of 2003 left 55 million people without power, for many as long as two days. This was caused by a software bug.

Much of the internet infrastructure was designed before there was significant demand for the web. Technical limitations have already affected the performance of the web. We ran out of IPv4 addresses (which each person requires to connect to the internet) in 2011, and ISPs have been slow to adopt IPv6 to solve the problem. The technical infrastructure may also be prone to attack, whether it be through cyber warfare (e.g., military assault) or malicious intent (e.g., hacking commercial infrastructure).

There may be political and commercial motivations behind changing the way we can access the web. The Great Firewall of China prevents people in China from accessing a huge portion of the web. Commercial motivations include ISPs prioritising particular services (e.g., Comcast’s proposals to degrade high-bandwidth services such as NetFlix), or companies choosing to change of discontinue services (e.g., Google withdrawing Reader).

Whether it be storing our photos with a cloud service or becoming reliant on a social network for communicating with friends, depending solely on these presents a risk to ourselves, in that loss of the web or these services will potentially be detrimental to our lives. The next post will be a case study into the Northeast blackout of 2003, in which a huge power cut led to widespread panic, and will consider the societal and economic impact of the event.

What is Anthropology Part 2: Theories and Fields no comments

Eriksen, T. H., 2004. What is Anthropology. London: Pluto Press.

“The raw material of anthropology – people, societies, cultures – is constituted differently from that of the natural and quantitative sciences, and can be formalised only with great difficulty…” (Eriksen, 2004, p 77). “[Anthropology’s approach] can be summed up as an insistence on regarding social and cultural life from within, a field method largely based on interpretation, and a belief (albeit variable) in comparison as a source of theoretical understanding” (Eriksen, 2004, p 81). Theory provides criteria by which to categorise data and to judge is significance. Anthropology applies theory to social and cultural data.

Fundamental questions

1. What is it that makes people do whatever they do?

2. How are societies or cultures integrated?

3 To what extent does thought vary from society to society, and how much is similar across cultures?

Anthropological theory is deeply tied to observation. Differences in approaches by region: US researchers favour linguistics and psychology and British favour sociological explanations (via politics, kinship and law).

Theory

There are 4 main theoretical underpinnings of Anthropological theory:

1. Structural-functionalism – A R Radcliffe-Brown: Demonstrating how societies are integrated. Person as social product. Ability of norms and social structure to regulate human interaction. Social structure defined as the sum of mutually defined statuses in a society.

2. Cultural-materialism – Ruth Benedict (1887-1948): Cultures and societies have ‘personality traits’.

Dionysian = extroverted, pleasure seeking, passionate and violent;

Apollonian = introverted, peaceful and puritanical;

Paranoid = members live in fear and suspicion of each other. Culture expressed seamlessly in different contexts – from institutional to personal levels.

Margaret Mead (1901 – 1978): sought to understand cultural variations in personality. Her highly influential work on child-rearing, Coming of Age in Samoa (1928) demonstrated that personality is shaped through socialisation.

3. Agency and society

Raymond Firth: Persons act according to their own will.

Pierre Bourdieu: Interested in the power differences in society distributed opportunities for choice unequally. Knowledge management: Doxa = what is self-evident and taken for granted within a particular society; Habitus = embodied knowledge, the habits and skills of the body which are taken for granted and hard to change; Opinion = everything that is actively discussed; Structuring structures = the systems of social relations within society which reduce individual freedom of choice. Important to understanding the causes that restrict free choice.

4. Structuralism – Theory of human cognitive processes.

Lévi-Strauss: the human mind functions and understands the world through contrasts in the form of extreme opposites with an intermediate stage (‘triads’). Cross-cultural studies of myth, food, art classification and religion. Based on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s observation in La pensée sauvage: “…in order to study Man, one must learn to look from afar; one must first observe differences in order to to discover attributes”. Post-structuralism more in favour today.

5. Primacy of the material – Strongly influenced by historical materialism (Marx). Gives primacy to material conditions of individuals above individual agency or how the mind works.

Two approaches within this area: those that favour economic conditions and those that give primacy to technological and ecological factors.

Julian Steward/Leslie White: Societies grow in complexity as a result of technological and economic change. Change happens in the ‘cultural core’ of technology, ecological adaption and property relations. The ‘rest of culture’ (e.g. religion, art, law etc) is more or less autonomous.

Gregory Bateson (Margaret Mead’s husband and one of the founders of cybernetics – i.e self-regulating systems) – all systems have properties in common: reaction to feedback (or lack of feedback) gives rise to repercussions which ensures the continuing re-imaging of the system.

6. Geertzian hermeneutics – interpretation of the world from the natives point of view.

Clifford Geertz: Thick description = a great deal of contextual description to elicit understanding of data. “…research primarily consists of penetrating, understanding and describing culture systematically the way it is experienced locally – not to explain it in terms of comparison…structuralist, materialist, or otherwise.”

Culture is expressed through shared, public symbols (communication) – so guessing the workings of the minds of those under scrutiny is unnecessary.

7. Eclecticism – a combined approach which recognises the complexity of the world and which attempts to “grasp both the acting individuals and the systemic properties constraining them”.

Fields

1. Reciprocity – the conduct of exchange, fundamental to sociality, crucial to human life.

a) Marcel Mauss – Gift-giving. The Gift (Essai sur le don, 1925). Three roles in gift-giving: obligation to give, obligation to receive and obligation to return the gift. Simplistic evolutionary view of society: i) Universal gift-giving fundamental to social integration (historical) ii) Institutions take on gift-giving role. iii) Marginal role for gift-giving in modern, alienating, capitalist societies. Exchange does not need to be economically profitable. “All economies have a local, moral, cultural element” (Eriksen, 2004, p 88). (Remnants of historical obligation are witnessed in round buying in pubs, dinner party invitations, circulation of second-hand children’s clothing among family and friends, voluntary community work, and Christmas. The potlatch institution (Boas) – where tribes seek to out-do each other in their extravagant wastefulness.

b) Karl Polanyi – Integration: reciprocity, redistribution and market principle. A radical critique of capitalism, directly relevant to ‘economic anthropology’. Rejects the view that people primarily strive to maximise utility (even if it happens at the expense of others). Psychological motivations are influenced by personal gain, consideration for others and the need to be socially acceptable. “Reciprocity is the ‘glue’ that keeps societies together” (Eriksen, 2004, p 91).

c) Marhsall Sahlins – 3 forms of reciprocity: balanced (e.g. tit-for-tat trade – close proximity ), generalised (gift-giving – family and friends), and negative (attempt to gain benefit without cost – strangers). Shows how “morality, economics and social integration are interwoven” (Eriksen, 2004, p 92).

d) Annette Weiner (Inalienable Possessions, 1992) – some things cannot be exchanged or given away as gifts, e.g. “…talismans, knowledges, [secret] rites which confirm deep-seated identities and their continuity through time” (Maurice Godlier, 1999). Cultural identity could be seen as an ‘inalienable possession’.

e) Daniel Miller (Theory of Shopping, 1998) – Sacrifice: women in buying at supermarkets purchase for others to form a relationship with them, and consider the views of others when buying for themselves.

f) Matt Ridley (The Origins of Virtue, 1996) – mathematical models show that cooperation ‘pays off’ in the long run.

2. Kinship – basis of social organisation. Not just family, but local community and work relations.

a) Lewis Henry Morgan – traditional societies thoroughly organised on kinship and descent.

b) Fortes and Evans-Pritchard – acephalous (‘headless) societies in Africa based on kinship-based social organisation. Segmentary system that expands and shrinks according to need – deeply influential in anthropology.

c) Lévi-Strauss – Alliance and reciprocity in kinship relations. Marriage in traditional societies is group-based and forms long-term reciprocity.

d) ‘Modern’ society – tension between family, kinship and personal freedom. Kinship is important in determining career opportunities

3. Nature

a) Inner nature – humans shaped by society and history, but with objective, universal human needs (Malinowski, Lévi-Strauss).

b) External nature – relationship between ecology and society, options are limited by environmental conditions, technology and population density.

c) Nature as a social construction – humans create representations of nature, which is often unspoken or not reflected upon – tacit knowledge.

d) Sociobiology – human actions cannot be be understood as pure adaption. “Research aims to establish valid generalisations about the mind as it has evolved biologically”.

4. Thought – people say what they think or express it through their acts, rituals or public performances.

a) Rationality – Evans-Pritchard’s 3 types of knowledge: i) mystical knowledge based on the belief in invisible and unverifiable forces; ii) commonsensical knowledge based on everyday experience; iii) scientific knowledge based on the tenets of logic and experimental method. Important, possibly unanswerable questions: i) is it possible to translate from one system of knowledge to another without distorting it with ‘alien’ concepts? ii) does a context-independent or neutral language exist to describe systems of knowledge? iii) do all humans reason in fundamentally the same way? Study of Technology and Science (STS) – science and technology as cultural products.

b) Classification and pollution – different people classify and subdivide them in different ways. Mary Douglas: classification of nature and the human body reflects society’s ideology about itself. What ‘pollution’, i.e. food prohibition, tells us about society.

c) Totemism – a form of classification whereby individuals or groups have special (often mythical) relationships to nature. Lévi-Strauss’ distinction between bricolage (associational, non-linear thought) and ‘engineering’ (logical thought).

d) Thought and technology

5. Identification a) The social b) Relational and situational identifications c) Imperative and chosen identities d) Degrees of identification e) Anomolies

Mind map: http://www.mindmeister.com/250242069

Basics of economics no comments

Fundamentals of economics

Looking at some early work on the subject, Adam Smith (the man with the invisible hand fetish … ‘it wasn’t me, it was my invisible hand…’) famously defined economics as “an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations” (1776), whilst Alfred Marshall painted an attractively casual picture of the “study of mankind in the ordinary business of life” (1890). Robbins (1932) is credited with a classic definition:

“Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between given ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.”

This does seem to capture the fundamental economic preoccupations of ideas of wants, choice, and scarcity quite well, but leaves me feeling a bit depressed about everything. Nevermind … on to the fundamentals bit:

Economists place a fundamental assumption about human nature at the heart of their discipline: that human wants are unlimited, and that people are driven by the satisfaction of these wants. The fact that the world in which we live is characterised by a limited amount of resources on which humans can draw means that humanity must compete for resources in conditions of scarcity. Scarcity is defined as “the excess of human wants over what can actually be produced to fulfil these wants” (Sloman, 2009:5). The resources for which we can compete are termed the factors of production, and are divided into three forms: labour; land and raw materials; and capital.

Economics, then, is concerned with the distribution of goods and services in these circumstances. The level of wealth among individuals or groups inevitably varies, so economics may examine how or why wealth is distributed in certain ways, or even look at methods in which different distributions of wealth might be achieved.

The interplay of the forces of supply and demand play a major role in economic analyses, to the extent that they “lie at the very centre of economics” (Sloman, 2009:5). The constant tension between these forces is expressed (in free or market economies) via the price mechanism, which responds to changes in the relationship of supply and demand (as a result of choices made by individuals and groups in an economy). If shortages occur, prices tend to rise, whereas surpluses allow prices to fall. In an idealised model of a market, an ‘equilibrium price’ can be reached in which the forces are balanced. Various signals and incentives help the operation of the price mechanism within and between markets.

The influence of shortages and surpluses on price affects consumers and producers in various ways, as the economic model of the circular flow of goods and incomes demonstrates. In this model, households (consumers of goods and services) buy goods and services from firms (producers), whilst firms buy labour, land or capital (the factors of production) from households, who might be compensated with wages, rent, or interest, for example. This ensures that incomes and goods continue to flow in the economy in the different markets which operate within it.

An important distinction in economics is between analysis of the overall processes and levels of activity of an entire economy on the one hand, and analysis of particular aspects of the economy on the other. The former is known as macroeconomics, whilst the latter is called microeconomics. Macroeconomics focuses on overall or aggregate levels of supply (output), demand (spending), and levels of growth (whether positive or negative) in an economy.

Macroeconomics examines overall supply and demand levels in order to explain or predict changes in levels of inflation, balance of trade (relationships of imports/exports), or recessions (periods of negative growth). In contrast microeconomics might focus on specific areas of economic activity (the production of particular goods or services), production methods, and the characteristics of particular markets. Microeconomics also examines the relationships between particular choices and the costs associated with them. Important concepts in this respect include opportunity cost, and marginal costs and benefits. When a decision is made, the opportunity cost is viewed as the best alternative to the actual course of action taken – “the opportunity cost of any activity is the sacrifice made to do it” (Sloman, 2009:8). This is an important consideration as it helps to determine the implications of economic decisions which need to be made. Economists assume that individuals make choices according to rational self-interest – making a decision based on an evaluation of the costs and benefits. This involves attention to the marginal costs or benefits of a decision – the advantages or disadvantages of increasing or decreasing levels of certain activities (rather than just deciding to do or not do something – the total costs/benefits).

As human understanding of the complex nature of the world and our activities within it has increased, economists have been forced to broaden the scope of their analysis to include certain social and environmental consequences of economic decision-making. Decisions which satisfy rational self-interest for individuals, groups or firms may nevertheless lead to outcomes such as pollution or extreme inequality which themselves have wider consequences for society and the economy as a whole (whether nationally or globally). Indeed, Sloman (2009:24) states that “[u]nbridled market forces can result in severe problems for individuals, society and the environment”. Growing recognition of these potential problems may help explain contemporary concern with sustainability, the role of government regulation of industry, and the creation of the concept of ‘corporate social responsibility’. As such, economists are asked to take account of economic and social goals of a society (as expressed through their government), and therefore contribute to their knowledge to help policy makers work toward these goals.

References

Library of Economics and Liberty (2012) What is economics? Available from: http://www.econlib.org/library/Topics/College/whatiseconomics.html [Accessed 10th November, 2013]

Sloman, J. (2009) Economics. 7th ed. Harlow: Pearson

Sloman, J. (2007) Essentials of Economics. 4th ed. Harlow: Pearson

Whitehead, G. (1992) Economics. Oxford: Heinemann

An Introduction & Initial Overview of Philosophy no comments

An Introduction & Initial Overview of Philosophy:

Philosophy is centrally a consideration of logical argument and reasoning offset in consideration of wider questions about every aspect of the universe. Philosophy is often misinterpreted as a loose collection of outlooks on life. Actually, it is about testing arguments to exhaustion in order to validate stances or viewpoints. An example of this is to consider the following statement that ‘murder is wrong’. Philosophy helps us to explore the notion of wrongness, considering why we define it as wrong and under, by counter critical argument, it could be right. It also asks us to consider alternative structures to the universe where, for example, murder may be considered right. Furthermore it asks us to consider about the idea of justifications- who is to say what is and is not right or wrong? Likewise can we apply the idea of universal principles to any situation and therefore form absolutes? As such you could say that Philosophy is the search for absolutes in unending open-ended questions- a search for specifics.

Socrates, Plato, Nietzsche, Hume, Descartes and Sartre are all Philosophers of noted mention; each contributes historical stances that have shaped schools of thought within the subject. Sartre, perhaps, is one of the less known key philosophers in his contributions to the field. A noted example is his branching of Philosophy and Literature, a good exemplification of the inter-disciplinary intrinsic nature of the subject that is a key underpinning process; the discipline is not so much a discipline, but a collection of different ways of thinking that consider a variety of options and inter-relate to one another.

Sartre’s novel ‘Nausea’ is a key example of an inter-disciplinary text; it explores philosophical stances of existentialism, questions about the nature of existence and our purpose within it, as well as a psychological literature that explores the barriers faced by individuals in a city-novel, which encapsulates and therefore enables relation to, for the reader, similar comparisons to their own lives. Through the novel Sartre offers a insight into how such influences create angst in the individual, the weight of the world gradually bearing down on them due to a variety of contextual factors unique to the city and individual. Through this he terms the idea of existential angst, opening up a range of existential themed emotions that relate to common fears and feelings about being fundamentally alone in a universe.

Such angst occurs from negative feelings and setbacks that are part of the experience of human freedom and responsibility. As a result such a novel demonstrates a more potentially reflective mirror to ourselves as it is read, considering how in the instance of the protagonist, their slip into depression, self-centred obsessed and eventual near-insanity enables us to draw reflections of our own barriers in everyday life that influence us to reflect negatively upon our existence. It also acts as a cautionary tale, shaping a consideration to how we should act and why. This is not so different to my initial example about how we define the notion of wrongness and murder- the justifications for our own decisions in life affecting what we consider to be acceptable or influencing our motivations, actions and responses as a result.

There are several key themes in Philosophy that are explored as a question of focus: God, Right and Wrong, The External World, Science, Mind, Art, Knowledge. All of these are more commonly integrated into specific schools of thought and summarised in a structured order that shapes the discipline itself; many, are in fact, interconnected and not singular subjects in their own right and each can be loosely affirmed into commonly related topics such as Reality, Value & Knowledge. In my next blog, I will consider more about the structure of Philosophy and arguments relevant to the topic explored for this report.

References:

1. Sartre, J.P, (1964). Nausea. New York: New Directions.

2. Warburton, P., (2012): Philosophy-the basics. London: Routledge.

Are Physical Geographers concerned with the Digital Divide? no comments

For this weeks reading, I have focused on Physical Geography. I have attempted to learn about the key concerns and research angles Physical Geographers focus on, and identify mean that they might consider and possible approaches towards the Digital Divide. Initially this may sound bizarre, why would the Physical Geography be relevant for an essay on the Digital Divide. Hopefully by the end of this blog post, you will have a better understanding as to why I have selected this subject, and have a clearer picture for my focus towards this essay in terms of Physical Geography and the Digital Divide.

Physical Geographers are concerned with:

1) Understanding the world better; how processes have become how they are; testing and refining theories related to these processes (Example processes include tectonic activity, climate change and the biosphere).

2) Understanding the effect we (humans) have on the environment from living in it and drawing the natural resources from it.

3) Predicting future changes of the environmental change, as well as measuring and monitoring these changes

4) Understanding how to manage and cope with the Earth’s systems and its changes

Geographers study the Earth in two periods of time; Pleistocene and Holocene. The Holocene Period, 11700 years ago to the present, is a significant period of time where humans have colonised globally, forming and building upon new relationships with the environment, for example agriculture and deforestation. Humans have taken control of plants and animals (genetic engineering and domestication) and over the years farming communities have rapidly grown. Agriculture, particularly farming, has enabled technological innovation to take place. As the more farming communities developed, the more food they could produce and provide for other societies that have little/no food production and instead focus on technology development. However, this has enabled the ability for humans to shape and transform the planet further and has brought consequences including soil erosion and impoverishment. Deforestation affects the eco system; it releases more Carbon Dioxide (CO2), a greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere. CO2 is a significant factor for global warming, effecting the temperature of the Earth, and currently concentrations are higher. This Climate Change is a great concern and research aspect for many Physical Geographers. Studies demonstrate that humans are contributing greatly to the issue of global warming; for example burning fossil fuels and biomass interferes with the Global Carbon Cycle. This is evidenced by the global climate models used. They demonstrate that when anthropogenic production of greenhouse gases is included in the stats, signs of global warming then appear. Developing countries makes up 5/6ths of the human population and will keep on increasing in population. This will result in burning more fossil fuels. Even if the richer countries have stabilised and decreased dependency on them, it will not necessarily be enough for protecting the environment. However if renewable resources are used and pushed by the developing countries, this may have a better impact of development for the environment.

Physical Geographers believe the future depends on the social, political and economic development but predicting these impacts is difficult.

This research has left me pondering on the following points:

1) To improve the digital divide it is only going to encourage humans to carry out current processes that affect the environment such as further deforestation to create more urban areas, and further fossil fuel burning to be able to use the technologies and carry out functions that are all deemed to better living standards?

2) Do the physical geographers actually want the digital divide to vanish – or at least not until it is known that it can be bridged without affecting the environment severely? As shown by the new NIC’s India and China, they are currently globalising at such a rate and without consideration for their emissions which are greatly impacting the environment.

3) Can it only get worse regarding the impact on the environment, to enable it to get better in terms of the digital divide? But then will it be too late to save our planet?!

4) Will closing the Digital Divide enhance Poverty instead of improve? -will it be a vicious circle of developing countries trying to develop, urbanise and become more technology based, a necessity for living (food) will be a struggle due to lack of food production countries, and as the environment will also be affected, it will be difficult for those farming communities still in existence to still be able to farm, thus preventing everyone that benefits/relies upon food production from others, to actually not improve/maintain quality of life and increase poverty?