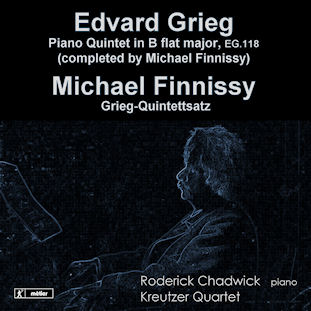

Finnissy and Grieg for five

Don’t miss a rare opportunity to hear Professor of Composition Michael Finnissy perform his own take on Grieg with the fantastic Kreutzer Quartet at Turner Sims on Monday 7 March, at 1pm. The concert will be followed by a composition workshop with the Kreutzers for Southampton undergraduate and postgraduate composers. Here Michael tells us about the process that led him to complete an unfinished work by Grieg and to match the result with his own new composition:

I was a bit startled when Paul Cox – Head of Strings at Southampton – asked me if I would complete an unfinished Piano Quintet by Grieg. Not an early work, not a deathbed testament, but a piece from Grieg’s maturity – neatly written out in his 1892 Sketchbook, the one he was using for revisions to his well-known music for Ibsen’s ‘Peer Gynt’. Roughly 250 bars from start to the end of the ‘exposition’, and no clues as to how it might continue. He had also reworked a theme from an earlier, even sketchier, 2nd Piano Concerto (c.1872), but no clues there either. I politely refused Paul’s invitation. He was disappointed, so I told him I’d mull over his suggestion. He was good-naturedly persistent. I finally gave in, telling him that I would also ‘re-live’ the process in a work of my own – following Grieg’s most likely sources (Norwegian folkmusic, Schumann, Wagner) which would not sound too remote from his, for roughly 250 bars, and then go off on my own musical journey, not trying to imitate Grieg.

Composers still begin, and then, at school or university, continue to learn reasonable management of their compositional imagination, by studying the ‘great masters’ of the past. If well taught, this is not so much learning to slavishly, or even effectively, imitate the sound of historical musics, as it is building up a set of useful principles. Principles that could be applied

regardless of stylistic, maybe even of generic, considerations. Although sometimes misleading (‘Why do I have to learn to write like Palestrina?’ ‘Surely Fugue is irrelevant in the 21st century?’) it remains invaluable in a culture where the music of the past not only continues to be performed and rightly revered, but where the music of the past dominates, almost to the point of exclusion, the music of the present. When people tell me they can’t stand the music I write, they sometimes go on to ask why I can’t write like Tchaikovsky or Paul McCartney.

Because Tchaikovsky and Paul McCartney did that already.

It took three attempts to get Grieg’s Quintet ‘right’, between 2007 and 2013, and I am sure there will be those who still think I failed to do so. But so be it: for me it represents the furthest swing of the pendulum of ‘transcription’, in many works which allude to our culture’s obsessive fetishising of the past, from Verdi to Gershwin, from Machaut to Mozart, from Japanese ‘naga-uta’ to free jazz. As a bewildered student, I took refuge from the RCM and my training, round the corner in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It was there that I decided to confront this nostalgic yearning for imagined musical Arcadias, and collect for myself a ‘cabinet of curiosities’ – writing through (trans-scribing) the entire history of Western European Music and its occasionally bizarre adventures.

How do I try to get Grieg right? Focussed thinking, research, analysis, trial and error, improvisation, hard slog. I listened to, and played through, all his chamber music, then a ton and a half of his solo piano works. Fortunately I like Grieg’s music, even if I have a few reservations about how it is put together. I am aware of, and understanding about, the cultural pressures that imposed limitations on his vision: most composers experience something similar – or I would have to, less enthusiastically, subscribe to the widely-held notion that he was a ‘miniaturist’, whose not infrequent attempts to compose in the more extended conventional forms, result in dismal failures.

Having no 100% reliable guide to how Grieg might have completed the quintet, I took my farthest step onto thin ice, deciding not to mimic the ‘obvious solution’ of a conventional sonata-first-movement (the excess of completed material would have made such a structure enormous and unwieldy) but follow a Lisztian design, in which the central ‘exploration’ of the material would act as a conventional Scherzo and Slow Movement, with a recapitulation (in which earlier string textures would be assigned to the piano, and piano textures re-written for the strings). The Scherzo and Slow Movement are also derived from small fragments of fast-moving material at the end of the exposition.

With hindsight, particularly recalling Grieg’s impact on Debussy and other French composers, some of the music has a decidedly Gallic flavour (as with the influence of Wagner, sound-worlds are often unspecifically ‘dans le vent’ and frequently disguised or denied). Eventually I

had added around 700 bars. The structural proportions are followed in my own ‘Grieg Quintettsatz’: opening with Lindeman’s ‘Ældre og Nyere Norske Fjeldmelodier’, continuing with a short allusion to Grieg’s ‘cello solo, to a free reminiscence of Brunnhilde’s dialogue with Siegmund in the second act of ‘Die Walkure’, to a concluding passage recalling traditional Hardanger fiddlemusic, bringing us to the 250 bars where Grieg broke off, but where I continued, after a moment’s respectful silence. A young friend told me that my own ‘continuation or exploration’ of this material sounded like a whirlwind tour of 20th century music: Ravel to John Cage, and maybe so. Who was it that said “Right you are if you think you are”?