The Oriental Miscellany – “Wild but pleasing when understood”

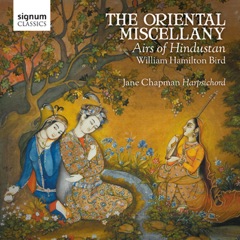

Jane Chapman, our Turner Sims Fellow and principal harpsichord tutor, has just released a new recording of the Oriental Miscellany (1789) – one of the earliest publications of Indian music in the West. Here she explains the project and talks with journalist Suanshu Khurana from the Indian Express (Delhi). Her disc is currently number 14 in the Indian iTunes Classical Charts (SIGDC415).

Jane Chapman, our Turner Sims Fellow and principal harpsichord tutor, has just released a new recording of the Oriental Miscellany (1789) – one of the earliest publications of Indian music in the West. Here she explains the project and talks with journalist Suanshu Khurana from the Indian Express (Delhi). Her disc is currently number 14 in the Indian iTunes Classical Charts (SIGDC415).

“remarkably colourful performances… florid ornamental flourishes unlike anything found in European music of the time” (Telegraph)

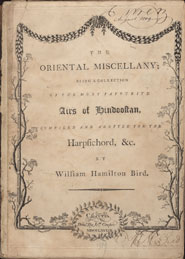

The Oriental Miscellany is the first published transcription of Indian vocal music in Western notation for harpsichord, taken from live performance. Arranged and adapted by William Hamilton Bird, and published by subscription in Calcutta in 1789, it is an important historical source, reflecting Western fascination with the East, and the vogue for Hindustani Airs. The publication consists of 30 short pieces in different vocal styles, and a Sonata with flute accompaniment which weaves at least eight of the airs into its various movements, perhaps the first work of East-West fusion. Playing Indian music on a harpsichord, filtered through late 18th-century notions of taste and culture, offers very interesting challenges. One of my main aims as a performer is to discover new repertoire, and search out and create music in collaboration with artist of all kinds.

How did you come across William Hamilton Bird’s book and how did this project exploring early musical encounters between the Indian sub-continent and the West come up? How and why did you decide to pursue it?

My partner for many years was the late Gerry Farrell, author of Indian Music and the West. We had met at Dartington College of Arts where we both studied sitar, and I had been with him to Delhi, where he had lessons with Ustad Debu Chaudhuri, with me listening in. His sitar often leant up against my harpsichord, and so it was very natural for us to play together, and as both are plucked string instruments, they really complemented each other. The sound of Indian music was always in my head, and we had frequent discussions on the way the West was always rediscovering the East and redefining it, which meant that the original music inevitably changed or evolved into something else through that process. He knew of the Oriental Miscellany and Hindustani Airs, which also appeared in books at the beginning of the 19th century, such as Crotch’s Specimens of Music – early forays into ethnomusicology. Gerry wrote about it in his book, drawing the strands together.

My partner for many years was the late Gerry Farrell, author of Indian Music and the West. We had met at Dartington College of Arts where we both studied sitar, and I had been with him to Delhi, where he had lessons with Ustad Debu Chaudhuri, with me listening in. His sitar often leant up against my harpsichord, and so it was very natural for us to play together, and as both are plucked string instruments, they really complemented each other. The sound of Indian music was always in my head, and we had frequent discussions on the way the West was always rediscovering the East and redefining it, which meant that the original music inevitably changed or evolved into something else through that process. He knew of the Oriental Miscellany and Hindustani Airs, which also appeared in books at the beginning of the 19th century, such as Crotch’s Specimens of Music – early forays into ethnomusicology. Gerry wrote about it in his book, drawing the strands together.

Before you began recording, tell me about the research that went into this project?

I received a grant from the Leverhulme Trust as artist in residence at the Foyle Special Collection Library (King’s College London), which has a rare copy of the publication, along with lots of other uncatalogued works. Looking at the original publication was a real thrill. I also compared it with a later version in the British Library. As part of my research I wanted to find out how the original songs sounded, and perform them with Indian musicians – recreating the music in reverse. This music does not seem to have been notated by Indian performers – it was passed down orally. The lyrics however, exist in another late 18th century collection known as the Plowden Manuscript, housed at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. My colleague Katherine Butler Schofield was able to match some of verse from the Plowden MS to the tunes in the Oriental Miscellany. Sophia Plowden was an accomplished harpsichordist, who along with her friend Margaret Fowke, collected these songs often heard at nautch or dance parties. The musicians would be invited home, and the songs transcribed, with the accompanying musicians tuning to the harpsichord. Sophia performed these pieces at soirées for friends drawn from the East India company, and even for the Newab of Awadh, Asaf-ud-Daula, at his court in Lucknow, where this music was popular.

Finding a way to draw this material together musically, and make it interesting, and not too repetitive, given the simple nature of the accompaniments, was rather tantalising. On the surface, this music due to the nature of notation, seems very straight forward in Western terms. It becomes a framework, perhaps a skeleton of the original. William Bird as a composer is not Haydn or Mozart, but he was trying to do something else, and genuinely transcribed and arranged these songs to suit the fashion of the time (such as adding a simple bass line) whilst being as true to the original as he saw it.

After much searching I found an Indian singer and tabla player (Yusuf Mahmoud). Yusuf is from Afghanistan, and it seems that some this music may have originated from that part of the world – it certainly resonated with him. He actually liked the tunes so much that he wanted to use one for his own song, and asked if he could do so, which I found really touching. I played the melodies (without Bird’s bass lines), and he picked them up from the harpsichord. We gave a concert together in the Chapel at King’s College London, with sarangi and tabla. He took the songs as a starting point for his own improvisations, as would be expected, when singing a ghazal for instance. One of the main things I learnt from him however, was which ragas the songs may have been based on, and I was able to try and give a flavour of the different ragas as introductions to some of the pieces in the recording.

Was there any specific preparation that was done for creating this album? I ask this because of the basic difference in Indian and western classical music, one of oral legacy and written notations. Indian music is a little bit like jazz, with a lot of scope for improvisation. Could you elaborate on your approach to the music while playing the pieces?

As a harpsichordist one is always expected to improvise. Part of the skill of a player is understanding how to harmonise a melody. In the baroque period composers would write figures under a bass line indicating which chords were expected to be played. This was known as figured bass – a little like understanding jazz chords. There is also a lot of ornamentation in 17th and 18th century Western music. This makes the harpsichord in particular sound much more expressive and sensitive, and also creates variety. One of my favourite kinds of pieces are the unmeasured preludes, which originated in France in the 17th century. These appear as a series of notes with no indication of rhythm, but with graphic swirly lines showing how the notes can be grouped together. This gives the player a lot of freedom, and has parallels with an alap coming at the beginning of a suite of pieces. I used this idea to introduce some of the songs and create the right mood. I went to a concert by the sitarist Nishat Khan, just before making the recording, and I found that very inspiring, particularly the patterns that he used in his improvisations. I also incorporated some of the material I had learnt in my sitar lessons, as I still have my notes in sargam. Bird actually composed many variations in a typical Western fashion, as a way of extending the songs.

As a harpsichordist one is always expected to improvise. Part of the skill of a player is understanding how to harmonise a melody. In the baroque period composers would write figures under a bass line indicating which chords were expected to be played. This was known as figured bass – a little like understanding jazz chords. There is also a lot of ornamentation in 17th and 18th century Western music. This makes the harpsichord in particular sound much more expressive and sensitive, and also creates variety. One of my favourite kinds of pieces are the unmeasured preludes, which originated in France in the 17th century. These appear as a series of notes with no indication of rhythm, but with graphic swirly lines showing how the notes can be grouped together. This gives the player a lot of freedom, and has parallels with an alap coming at the beginning of a suite of pieces. I used this idea to introduce some of the songs and create the right mood. I went to a concert by the sitarist Nishat Khan, just before making the recording, and I found that very inspiring, particularly the patterns that he used in his improvisations. I also incorporated some of the material I had learnt in my sitar lessons, as I still have my notes in sargam. Bird actually composed many variations in a typical Western fashion, as a way of extending the songs.

What were the most fascinating aspects of recording this album?

I was very lucky to be allowed to record at the Horniman Museum, London, on an original Kirckman harpsichord from 1772 that had just been restored. This English harpsichord is exactly the type of instrument that would have been exported to India, and the particular model I played was certainly top of the range! It has two manuals and various different stops and pedals which engage the strings, and other devices, such as a nag’s head swell, allowing me to create a variety of timbres and even dynamics. My favourite sound is one which is rather like a tanpura on the top manual. I was able to recreate the drone effect that way, whilst still playing the melody on the lower keyboard. This particular instrument enabled me to add colour to the music and create as much variety as possible.

Part of the glory of Indian music is its rhythmic flexibility. Tying it up may not make it sound spontaneous. Did you fear that?

Yes – I did. Bird was also very aware of this, and in his introduction to the Oriental Miscellany makes this clear particularly when writing about the Raagney, saying that they are “so void of any meaning, and any degree of regularity, it is impossible to bring them into any form for performance, by any singers but those of their country.” The songs need the grace of a Chanam (female singer) and the expression of a Dillsook (male singer) “to render them pleasing”. Much of this music was however quite regular, and possibly accompanied dance performed at nautch parties. Bird talks about the repetitive nature of some of it, so some of the tunes may have acted as lahra – repeated rhythmical, melodic phrases. My way of trying to create a sense of spontaneity was, whenever possible, to imagine the romantic nature of the poetry, and think how a singer may present the words, and to come up with ornamentation that felt as if it came from the baroque period, but had an Indian feel. Some of the songs have really evocative titles such as “Who are you, beautiful cypress-like one” which is a Persian ghazal by a famous poet.

I was reading that Bird didn’t really notate the micro tones or what we refer to as shrutis, thinking that a harpsichordist would be able to create them anyway. Do you agree? While playing the pieces, did they come naturally?

The harpsichord is rather like a harmonium as the notes are fixed and cannot be ‘bent’ as on a sitar, or with the voice. I’m glad if you feel that there is some sense of this! The tuning that I used was not equal temperament (like a modern piano). I used a baroque tuning that was popular at the time which means that some of the intervals have different colours. This could add to the sense of musical flexibility.

There is a certain fluidity that I can spot in the melodic lines. Did you make any changes along the way or did you stick to the original notations?

I was really aiming for this, as my general approach to notation, is that it doesn’t tell the whole story even in Western music. It depends on the genre and style, and I felt that coming back to the words, and the nature of the harpsichord (plucked strings without much dynamic range), that subtle rhythmic manipulations, and the use of ornamentation, give the tunes more life, energy and meaning. The instrument also speaks as an individual – it’s not the same as playing digital keyboard, as it has its own voice which demands expression.

What were the challenges you faced while working on the album?

I was very lucky that so many things came together at the right time, such as the instrument being available, and the research grant. I also had help from the University of Southampton where I am Turner Sims Fellow. Musically my main challenge was capturing the different moods of the pieces, and thinking how each one would lead to the next. When Bird put the collection together, he probably never imagined that it would all be played at one sitting, but that favourite songs would be selected to entertain. Making a continuous CD has its challenges, though of course these days people tend to download individual pieces, and may listen to a Hindustani Air followed immediately by punk rock.

You have created something quite interesting. As western classical as harpsichord is, it sounds quite Indian, while playing the tappas and other compositions I heard. What was your idea in terms of achievement. What is it that you wanted to derive out of this album except satisfaction?

I really wanted to bring this music to life, and make something which looks so straightforward on the page have some meaning and emotional appeal. I also felt very privileged that I had received some education in Indian music, and also collaborated with different kinds of musicians. This was a way of drawing my varied experiences together, and sharing them with others.

The great bulk of the standard repertoire for the harpsichord was written during its first historical flowering, the Renaissance and Baroque eras. Could you briefly discuss the relevance of the instrument in today’s day, especially because of the popularity it has acquired in popular culture, appearing frequently in films, computer games among others.

One of the most popular songs is Golden Brown by the Stranglers. I was watching a video of it last night made in the 1980s, and interestingly the harpsichord becomes something quite exotic against a backdrop set in Egypt with a very Eastern feel. The rhythm of the song is also quite complex for a pop song – it could have been a Hindustani Air! I play a lot of contemporary music – some of it is quite avant-garde, and have premiered over 200 works, including live electronics, some of which I recorded on a disc called WIRED (NMC). Composers find that writing for this instrument creates new challenges, and though it has some cultural baggage from a previous age, it can offer a different sound world to the piano. Ligeti wrote the first really contemporary piece for the instrument in 1968 called Continuum which completely transforms the instrument. I also work with electric guitarist Mark Wingfield, and we have an album out – Three Windows – with sax player Iain Ballamy. There’s a new one with jazz percussion, released at the end of this year.