Pianos on the high seas

Postgraduate researcher Anna Borg Cardona has uncovered maritime musical connections between Southampton and her home country of Malta:

By 1814, Malta had become a British colony. British families soon began to settle on the Islands, accompanying army and navy personnel who were posted there. Some families transported their own musical instruments with them. Recognising potential commercial opportunities, merchants also began to establish a base on the Islands. Malta became a fertile ground for commerce, including the sale of musical goods.

During the early nineteenth century, most musical instruments had been reaching Malta from Naples, Trieste and Marseille. However, by the 1840s there was a noticeable increase of goods from Great Britain, with Southampton being one of the main ports from which musical instruments were being shipped, most frequently aboard the Oriental.

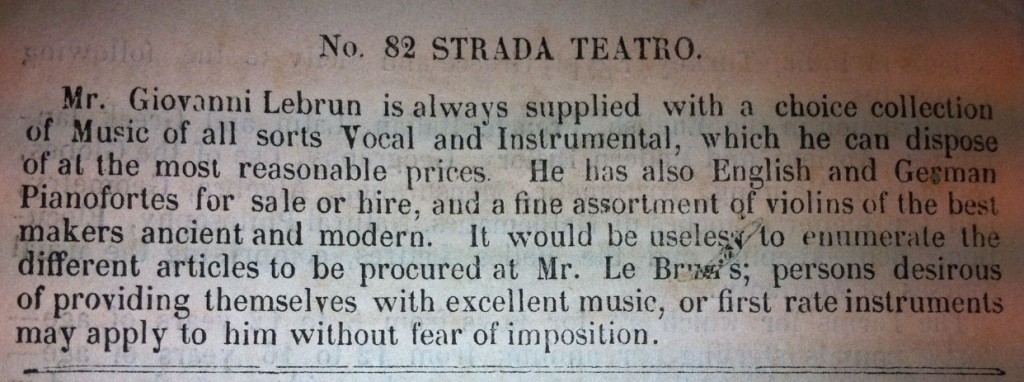

While walking down the Southampton High Street I could not help noticing a metal slab that recorded an important landmark in the city’s history: in the 1840s major new docks were built on reclaimed lands and ‘the railway connected the port to the rest of Britain’. This explains the increased shipments to Malta at precisely this time. The railway facilitated the transport of larger musical instruments such as pianofortes from different areas of Britain to the port of Southampton. In 1842, according to Il Portafoglio Maltese (a Maltese newspaper published in the Italian language) we find cases of musical instruments, pianofortes and harp strings arriving in Malta from Southampton. That same year the musical outlet of Giovanni Lebrun in Valletta began advertising ‘English and German Pianofortes for sale and hire’ which suggests that there was now a regular supply reaching the Islands. The following year several pianoforti arrived from Liverpool, Glasgow and Southampton, and in 1844, more pianoforti, as well as ‘boxes of instruments’ continued to arrive from Southampton (PM, 29 Jan. 1844).

While walking down the Southampton High Street I could not help noticing a metal slab that recorded an important landmark in the city’s history: in the 1840s major new docks were built on reclaimed lands and ‘the railway connected the port to the rest of Britain’. This explains the increased shipments to Malta at precisely this time. The railway facilitated the transport of larger musical instruments such as pianofortes from different areas of Britain to the port of Southampton. In 1842, according to Il Portafoglio Maltese (a Maltese newspaper published in the Italian language) we find cases of musical instruments, pianofortes and harp strings arriving in Malta from Southampton. That same year the musical outlet of Giovanni Lebrun in Valletta began advertising ‘English and German Pianofortes for sale and hire’ which suggests that there was now a regular supply reaching the Islands. The following year several pianoforti arrived from Liverpool, Glasgow and Southampton, and in 1844, more pianoforti, as well as ‘boxes of instruments’ continued to arrive from Southampton (PM, 29 Jan. 1844).

Pianofortes of every kind became a form of social aspiration for both British and Maltese families. The early decades of the nineteenth century coincided with the development and increase in production of the relatively more affordable upright piano and the square piano – usually referred to as piano forte a tavolino, because when closed it looked like a table. Though in Malta there seems to have been a general preference for German pianos, advertisements in Maltese newspapers show the sale of several new and second-hand British pianofortes mentioned by maker. Among them we find un gran piano-forte di Broadwood di un tono sonoro (1838), un eccellente piano-forte a tavolino di Broadwood (1839), due pianoforti a tavolino di Tomkison (1841) and a piano forte Butcher (1841).

Pianofortes of every kind became a form of social aspiration for both British and Maltese families. The early decades of the nineteenth century coincided with the development and increase in production of the relatively more affordable upright piano and the square piano – usually referred to as piano forte a tavolino, because when closed it looked like a table. Though in Malta there seems to have been a general preference for German pianos, advertisements in Maltese newspapers show the sale of several new and second-hand British pianofortes mentioned by maker. Among them we find un gran piano-forte di Broadwood di un tono sonoro (1838), un eccellente piano-forte a tavolino di Broadwood (1839), due pianoforti a tavolino di Tomkison (1841) and a piano forte Butcher (1841).

Some instruments that arrived in the early decades have remained in Malta and are now in private or public collections. Among these is an 1804 John Broadwood fortepiano, now in the Wignacourt Collegiate Museum in Rabat, Malta, and a Broadwood from the 1840s, which is privately owned.

Anna has written a fuller account of the instrument trade in 19th-century Malta in her article, ‘Malta’s importation and sale of musical instruments and musical goods, 1800-1900’ published last year in A Timeless Gentleman, Festschrift in honour of Maurice de Giorgio, Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti (Malta, 2014): 397-409.