Concerts in Playhouses, plays in concerts: The Tempest or The Enchanted Isle

Southampton’s Head of Early Music, lutenist Elizabeth Kenny, has been in the news recently with rave reviews of an unusual version of Shakespeare’s Tempest at the Globe Theatre’s new playhouse:

I’m spending a lot of time at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at the moment. A couple of programmes I was invited to devise for the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment gave us the opportunity to connect music and theatre in a way that the indoor playhouses, of which this is a model, were expressly designed to do. For the audience the experience is nowhere near as comfortable: you have to be up for sitting upright on wooden benches with your face illuminated to those onstage as much as in the other direction, but in return you get a magical experience of being part of the action, and acoustics that – especially to a player of a quiet instrument like to the lute – are to die for.

Royal Opera saw the potential for staging more close-up versions of baroque pieces that get lost in the main Opera House, and engaged the Early Opera Company to be the band for their first Wanamaker production, Cavalli’s L’Ormindo. Playing theorbo and guitar in the musicians’ gallery in January-February 2014 was like playing baroque opera for the first time. Sometimes in big houses as a continuo player you have to gang up and play as loud as possible all the time, and the singers feel miles away: generally there seems to be a rule that when a piece of recitative is low in a singer’s voice or quiet, they will be facing away – a long way away! – upstage. There is a certain amount of fun in this – it’s a bit like playing pinball, aiming your chord and hoping it sticks in the right place. But the revelation of two-way hearing and communication that is playing for singers only feet away, the audience aware of every nuance and dynamic shading, was addictive: I’m writing this in a rehearsal break for the revival in February 2015.

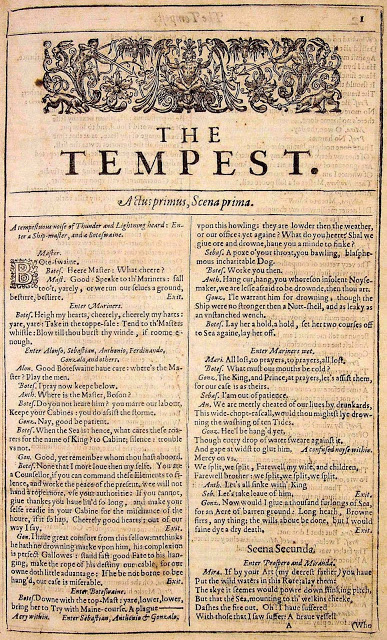

In seventeenth-century England spoken drama mixed easily with music, just as it does on the West End stage. The Globe kindly set me up with a couple of actors and writer-director and off we went into the Davenant-Dryden-Shadwell version of the Tempest first performed in 1674. We had small forces – string quartet, theorbo, archlute (to supply the high notes missing without a harpsichord and for quiet underscoring especially with Ariel, to evoke his musical magic). Three adult singers (Sam Boden, Katherine Watson, Frazer Scott) sang the Ariel songs and masque music: Neptune and Amphitrite who are conjured by Prospero to resolve the damage done by the winds and the storm, and two boy trebles (Harry Cookson, Andrew Sinclair-Knopp) were lured by the promise of coming up through the trap door to sing the devils who torment the corrupt sailors. Caroline Williams brilliantly compressed the exuberant text, using her knowledge of the space as a Wanamaker regular, to imagine and direct all sorts of effects from balcony exchanges of masks between actors and singers to actors wandering around the audience offering them fruit for the banquet which Ariel makes materialize.

In seventeenth-century England spoken drama mixed easily with music, just as it does on the West End stage. The Globe kindly set me up with a couple of actors and writer-director and off we went into the Davenant-Dryden-Shadwell version of the Tempest first performed in 1674. We had small forces – string quartet, theorbo, archlute (to supply the high notes missing without a harpsichord and for quiet underscoring especially with Ariel, to evoke his musical magic). Three adult singers (Sam Boden, Katherine Watson, Frazer Scott) sang the Ariel songs and masque music: Neptune and Amphitrite who are conjured by Prospero to resolve the damage done by the winds and the storm, and two boy trebles (Harry Cookson, Andrew Sinclair-Knopp) were lured by the promise of coming up through the trap door to sing the devils who torment the corrupt sailors. Caroline Williams brilliantly compressed the exuberant text, using her knowledge of the space as a Wanamaker regular, to imagine and direct all sorts of effects from balcony exchanges of masks between actors and singers to actors wandering around the audience offering them fruit for the banquet which Ariel makes materialize.

Playing for actor rehearsals is a new experience for me, and the physicality of Molly Logan and Dickon Tyrell’s performance was exhilarating to watch as it came out of the lines, from one actor playing two characters killing each other in a duel, to morphing between male and female characters, to planting Prospero’s staff in a handy hole in the stage (“Too Lord of the Rings?” we wondered before going with it anyway, and Gandalf-Prospero, Gollum-Caliban, Blond Elf-guy-Ariel turned out to be useful when I was giving my 12 year old son a handle on the plot before he watched the show…). Getting it in the space in three hours having rehearsed elsewhere was a challenge: for the musicians it’s all about the right chairs and enough light to see by, for the actors whether they could run down stairs in time after the storm music to become Miranda and Prospero. I was glad I knew the place on the second night when they were upstairs needing to get down, so a little bit of lute improvisation was needed and just as I was wondering what key to go into next they burst through the doors…watching the masked heads of the boys emerge from the trap to the audience’s delight and the sound of a hurdy-gurdy was an experience to remember. Look out for these cool young men in the future!

Playing for actor rehearsals is a new experience for me, and the physicality of Molly Logan and Dickon Tyrell’s performance was exhilarating to watch as it came out of the lines, from one actor playing two characters killing each other in a duel, to morphing between male and female characters, to planting Prospero’s staff in a handy hole in the stage (“Too Lord of the Rings?” we wondered before going with it anyway, and Gandalf-Prospero, Gollum-Caliban, Blond Elf-guy-Ariel turned out to be useful when I was giving my 12 year old son a handle on the plot before he watched the show…). Getting it in the space in three hours having rehearsed elsewhere was a challenge: for the musicians it’s all about the right chairs and enough light to see by, for the actors whether they could run down stairs in time after the storm music to become Miranda and Prospero. I was glad I knew the place on the second night when they were upstairs needing to get down, so a little bit of lute improvisation was needed and just as I was wondering what key to go into next they burst through the doors…watching the masked heads of the boys emerge from the trap to the audience’s delight and the sound of a hurdy-gurdy was an experience to remember. Look out for these cool young men in the future!

You can hear Elizabeth Kenny and Catherine Williams talking about the production in this video: