Orpheus in the round

Professor of Music Jeanice Brooks made a field trip to hear one of her favorite operas: Last week I went along with some of my Southampton Music colleagues to see Claudio Monteverdi’s Orfeo. Composed in 1607, it’s the earliest opera that is regularly staged today. It’s a piece I completely adore, and though I teach it both in first year music history and in a specialised module on Monteverdi for second and third years, I’ve had only a few chances to see it in the theatre. I was particularly keen to see this new production: it’s the first time the Royal Opera House has done Orfeo, and it was the ROH’s first-ever collaboration with the Roundhouse, one of London’s newest and most unconventional arts venues. The production also moved outside ROH norms in other ways. Directed by Michael Boyd, artistic director of the RSC rather than an opera regular, it had a chorus of students from the Guildhall and dancers from community groups mixed in with the professional singers and players.

There was quite a lot of Southampton Music involvement too – our Head of Early Music, Liz Kenny, starred in the continuo group (on both theorbo and baroque guitar); Joe Crouch, who just finished a research fellowship here, was the cellist. And our own Valeria De Lucca contributed the historical notes on Orfeo for the programme.

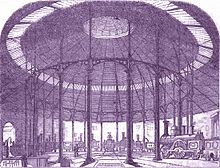

The Roundhouse, which started life as a turntable engine shed, is a fascinating if challenging place for opera performance. It’s a circular stage with no pit, so the instrumental forces were ranged along one side (if a round stage can have a side) with the keyboard instruments – two harpsichords, regal and organ – stacked up like Lego. Seeing the early instruments framed by bits of 19th-century Industrial Revolution technology, such as the elaborate pillars of the building’s cast iron support structure, reminded me that the instruments themselves were marvels of Baroque engineering in their own time.

The Roundhouse, which started life as a turntable engine shed, is a fascinating if challenging place for opera performance. It’s a circular stage with no pit, so the instrumental forces were ranged along one side (if a round stage can have a side) with the keyboard instruments – two harpsichords, regal and organ – stacked up like Lego. Seeing the early instruments framed by bits of 19th-century Industrial Revolution technology, such as the elaborate pillars of the building’s cast iron support structure, reminded me that the instruments themselves were marvels of Baroque engineering in their own time.

The opera was given in English instead of Italian, which is also unusual (early music is fairly rarely performed in translation these days) but was a further way to break down one of opera’s traditional barriers to new audiences. The new translation, by Don Paterson, had some beautiful passages but in the end I didn’t buy it. English has too many final consonants and other features that changed the way the vocal phrasing has to work, and I often felt as if the English words were fighting with Monteverdi’s music. Though I wasn’t convinced about the musical effect, the translation did make room for some directorial twists. The first act of Orfeo is full of shepherds and shepherdesses dancing around celebrating Orpheus’s impending marriage. In this production, Monteverdi’s pastori (shepherds) turned into ‘pastors’ in English, and were cast as priests carrying out the wedding ceremony. Modern producers can find some aspects of Baroque pastoral tricky to handle without being precious or twee, so getting rid of the shepherds altogether was one way to get round that problem.

The production had some good moments, especially in the section after Orpheus goes into Hell to plead for Euridice’s release. But it was really worth going to mainly for the musical quality. The playing was fantastic (and I am not just saying that because my friends are in it – the reviewer from the Financial Times said ‘it’s the band that gives this production its oomph’ and he was right). And the singing was consistently excellent, with especially fine performances from Gyula Orendt (Orpheus), James Platt (Charon), and countertenor Christopher Lowrey (doubling as one of the pastors and the allegorical figure of Hope). I loved Susan Bickley as Silvia, the messenger who brings the news of Euridice’s death; she brought a wonderful richness and expressivity to the role, which is often sung by lighter voices to much less telling effect.

Orfeo was live streamed from the Roundhouse on 21 January and you can watch it on demand for another six months. It’s definitely worth seeing – a good introduction to Monteverdi’s music for beginners, and a thought-provoking take on the piece for people who know and love it.