Archive for the ‘Criminology’ Category

Criminology – Thinking about some basics no comments

It’s admittedly been a while since my last post, but I have still been a bit scattered about the nature of my topic and have been earnestly trying to refrain from focussing on Web Science issues that are too narrow and specifically, archaeological. In lieu of this I’ve been focused on getting to grips with Criminology first, a discipline which I know I want to study and apply elsewhere. I’ve been taking lots of notes along the way, but hadn’t yet transcribed them here, so here goes..

The following mostly stems from Walklate 2005: Criminology: The Basics.

What is Criminology?

Criminology as Multidisciplinary

One of the big take home points for me about Criminology as a discipline is actually how inherently multidisciplinary it is. Depending on who you ask, you might get a somewhat different take on the nature of criminological study, typically framed by the ‘other discipline’ from which the researcher stems from. This includes criminology from an economics, history, psychology, law, sociology, anthropology, and philosophical multidisciplinary stance – all researching and defining criminology somewhat differently. Yet Walklate claims all disciplines are “held together by one substantive concern: CRIME.”

What is Crime?

The question of “what is crime” within the criminology community is contested, and seems to go beyond defining crime as simply breaking the law though this is a useful starting place for most researchers, as it removes the emotive nature of studying such a subject area. But criminologists must also consider that laws change, thus understanding the processes of criminalizing and decriminalizing and the processes that influence policy can also fall under the remit of criminology. Criminologists must also consider social agreement, social consensus and societal response to crime, which extends the crime definition beyond that which is simply against the law. In addition, crime still occurs regardless of the content of the law – and this falls within a sub sect described as “deviant behaviour” which seems to lend itself more to the psychological-criminological studies.

Sociology of Crime

The sociology of crime is concerned with the social structures that lead to crime – “individual behaviour is not constructed in a vacuum” – and it takes place within a particular social and cultural context that must be examined when looking addressing criminal studies. Social expectations and power structures surrounding criminal acts are also important to the nature of studying crime in society.

Example applications and questions

- Why does there seem to be more of a certain type of crime in some societies and not others?

- Why/If the occurrence of a type of crime is changing throughout time?

- Why do societies at times focus efforts on reducing/managing/effecting certain types of crimes?

feminism – forced a thinking about the “maleness of the crime problem”, and question of masculinity within society – “search for transcendence” (to be master and in control of nature)

Counting Crime

Sources for analyzing crime

- direct experiences of crime

- mediated experiences of crime

- official statistics on crime – Criminal Statistics in England and Wales, published yearly a good starting point. Home Office, FBI, EuroStat

- research findings of criminologists

“the dark figure of crime” – the criminal events only known to the offender and the victim – e.g. those that don’t get caught, or not reported/recorded.

Not all recorded offenses have an identifiable offender/not all offenders are convicted – partiality

The 3 R’s: recognising, reporting, recording.

Reporting – criminologists must understand reporting behaviour and reasons for not reporting crime, and then how that effects the results/statistics upon analysis.

- behaviour may be unlawful but witnesses may not recognise it as such, thus not report it

- witnesses may recognise an act as criminal but consider it not serious enough to report

- judicial process – and numbers of tried vs convicted, the politics of this and its subsequent effects in reporting

- police discretion on recording crime – e.g. meeting and reporting to targets

identifying trends – it’s important to understand crime statistics over time

- understand whether crime and terms for crime change over time, changes to how an offense is defined

- criminal victimisation surveys – do these exist for Internet fraud

- crimes against the personal vs crimes against property

the Problem of Respondents – getting people to respond to surveys can be challenging.

- big difference between crimes known to police and the dark figure of crime

- big difference between crimes made visible by criminal victimisation surveys and those that remain invisible (e.g. tax fraud)

Archaeology, crime, and the flow of information. no comments

Whether it be from property developers, civil war and conflict, treasure hunters and local enthusiasts, or just “bad archaeology”, archaeologists and heritage professionals have long struggled with the question of how to ensure the protection of sites, monuments and antiquities for future generations. Archaeological method and “preservation by record” were historically born out of situations where archaeology can not be conserved and within a desire to uphold one of the main principles of stewardship: to create a lasting archive. As archaeology is (very generally speaking) a destructive process that can not be repeated, an archive of information regarding the context and provenance of archaeological sites and finds is created to allow future generations to ask questions about past peoples.

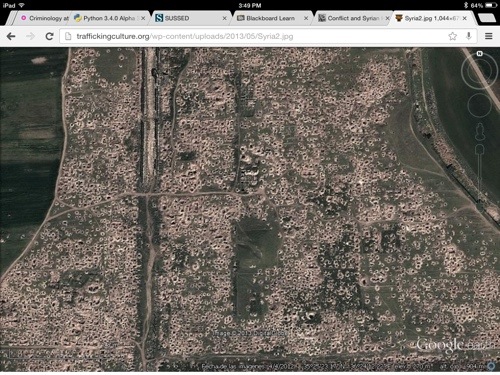

Recent years have presented numerous ethical challenges to archaeologists and and other stewards of the past, particularly where crime and illicit antiquities are concerned. Social media and web technologies in general have provided, in some cases, real-time windows into the rate of the destruction of heritage sites within areas of war and conflict. Evidence from platforms such as Google Earth, Twitter, and YouTube have all been used by world heritage stewards to plead for the protection of both archaeological sites and “moveable heritage”. Ever-evolving networks of stakeholders in the illegal antiquity trade have also been identified and linked to looted sites in areas where some have hypothesized that the sale of antiquities is actually funding an on-going arms trade in regions consumed by civil war.

Although a case could be made for investigating the nature of archaeology and crime from the angle of many different disciplines (philosophy, ethics, economics, law, psychology, to name a few), criminology and journalism were specifically chosen to offer insight into the role of the Web as a facilitator in the flow of information. Both disciplines are concerned with information flow and resource discovery – for example, in journalism the flow of information between (verifiable) sources of information through to dissemination to the public, and in cybercrime the important information exchange that drives networks of crime (both physical and virtual).

Focusing on the nature of information exchange, what would criminology and journalism contribute to the following topics?

- Social media and the dissemination of heritage destruction. What are the ethical issues surrounding the use of social media sources in documenting heritage destruction? Can/should social media sources (sometimes created for other purposes) be used as documentation to further research or conservation aims within archaeology?

- The international business of selling illicit antiquities – from looters to dealers – what role does the Web play in facilitating these networks of crime? What methods for investigating cybercrime could be applied to the illicit antiquities trade to better understand the issues surrounding provenance?

- Does the “open agenda” and the open data movement specifically (e.g. online gazetteers of archaeological sites, open grey literature reports with site locations, etc.), create a virtual treasure map and subsequently increase the likelihood of looting at archaeological sites?

Some aspects of each discipline which I believe to be relevant to the study of each (as well as the chosen topic):

Criminology and Cybercrime

- What is crime? (“The problem of where.“/”The problem of who.“)

- Policy and law

- Positivism and the origins of criminal activity.

- Digital Forensics

Journalism

- What is Journalism?

- Who are Journalists?

- Ethics and Digital Media Ethics

- Anonymity, Privacy and Source

- Bias and Conflicts of Interest

Some Potential Sources

Criminology:

Burke, R.H., 2005. An Introduction to Criminological Theory: Second Edition. Willan Publishing.

Walklate, S., 2007. Criminology: The Basics. 1st ed, The Basics. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Yar, M., 2013. Cybercrime and Society. 2nd ed., London: SAGE.

Journalism:

Ess, C., 2009. Digital Media Ethics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Frost, C., 2011. Journalism Ethics and Regulation. 3rd ed., Longman.

Harcup, T., 2009. Journalism: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed., SAGE.

The Digital Divide:- Geography and Criminology no comments

The Digital Divide has become a popular term, commonly understood as the gap between those that have access to the internet and those that do not. Initially it is assumed this gap is simply between the developed and developing countries, also known as the Global Divide. However, there are other distinct aspects of the divide; Social divide – the gap within each nation, and the Democratic Divide – those who use/do not use digital resources in their pubic life.

Although there are several efforts and schemes in place with the hope of bridging the gap, it is a great issue that is highly unlikely to be solved in the near future. In fact it is most probable that the gap will carry on growing, increasing the difficulty of bridging it.

This topic has always intrigued me. I believe this is a great opportunity to research the matter through the perspectives of Geography and Criminology.

> Geography

Geography, the study of “the world around us”, already draws upon a range of disciplines including sociology, anthropology, geology, politics, and oceanography.

It is divided into two parts; Human and Physical Geography. Although I will hope to cover both parts, I believe my research will heavily focus within the Human side of Geography, as it emphasises on the changes of the world effected by human interventions.

I anticipate to discover research amongst one of the main topics of Geography; Globalisation – a defined term used since the 1990s describing the characteristics of the world we live in.

> Criminology

With absolutely zero previous experience in the field of Criminology, I hope this will give a different insight to the Digital Divide in comparison to Geography, and with a closer focus on the topic, such as social inequality.

Light research has already demonstrated there is a vast interest in crime and criminals, and that crime varies throughout different societies. There are several explanations criminologists have composed from Biological explanations to Social and Psychological explanations. There are also several different theories created to explain reasons for crime including the Economic and Strain theory.

> Resources

To date, the following books appear to be of great use and help towards this research study:

Daniels, P., Bradshaw, M., Shaw, D., Sidaway., (2012) An Introduction to Human Geography, 4th ed, Essex: Pearson

Moseley, W., Lanegran, D., Pandit, K., (2007) Introductory Reader in Human Geography Contemporary Debates and Classic Writings, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Hale, C., Hayward, K., Wahidin, A., Wincup, E., (2009) Criminology, 2nd ed, New York: Oxford University Press

Norris, P., (2001) Digital Divide, Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide, New York: Cambridge University Press

Criminology: Overview and Brief History. no comments

I have decided to start by learning the principles which underlie criminology and philosophy. I start by asking, what is criminology? Then I go on to give a brief history of criminology.

After trawling the net for some time, paying particular attention to university websites, I decided to use “The Oxford Handbook of Criminology” by Mike Maguire, Rod Morgan and Robert Reiner as my core textbook, almost everything below is indebted to them.

What is Criminology?

Criminology draws from an amalgam of subjects such as law, sociology, phycology, psychiatry, history and anthropology in order to answer questions like, what are the causes of crime? What are the ethnographic s of certain deviant groups? What can we learn from case studies of individual criminals? Can we predict future crimes and future perpetrators of crime? Why are some people criminals and others not?

This begs the question, why did Criminology become a discipline in its own right? Maguire, Morgan and Reiner suggest that it was contingent upon the exertions of discipline forming institutions and dominant individuals.

They then go on to discuss the emergence of criminology as a discipline. It is suggested that criminology is the synthesis of two schools of thought. The first is government – who want to know how to best create laws and govern with respect to crime and criminals. The other school of thought comes from an Italian anthropologist Cesare Lombroso(1835-1909) who thought that people could be divided into two category, criminals and non-criminals, Lombroso went so far as to claim that there is a biological difference between criminals and non-criminals.

With a hard science a scientist or group of scientists produces a theory and evidence to back it up. Then they write it down in the form of a paper which is peer reviewed and then either accepted or not accepted into the scientific community. If a theory is accepted within the scientific community it is then accepted in the general public for example the theory of Black Holes. On the other hand a scientific theory accepted in the criminology community is not always accepted by the general public. The “common sense” view of the world is often much more powerful.

In order to understand the principles of Criminology it is useful to detour into some History.

A Brief History of Criminology

The history of criminology turns out to be a fiercely contested, vague and ugly. In fact the word criminology was only coined in the 1890’s and what we think of as criminology today (the current paradigm if you like) only crystallised in the 1960s and 70s, and even that’s debateable. The history of criminology is further confused, because what was thought of as “criminology” differed in France, Germany, England, Italy and the U.S.

To illustrate the history of criminology I have created a timeline with significant events and the socio-economic backdrop for these events. My apologies, especially to Paul and Javier that it’s not fantastically beautiful! Hopefully the timeline helps to elucidate the history of criminology, which is contingent upon sociological events. For example, criminology, it is argued by Maguire, Morgan and Reiner, really started in the 18th century, which was also the time when a network of insane asylums and doctors attending these asylums emerged in Europe. Maguire, Morgan and Reiner further argue that since a significant proportion of inmates in the asylums were also criminals, for the first time doctors were concerned with understanding the criminal mind.

Then throughout the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th prisons were invented and governments became stronger. As a result governments, especially in the UK, became interested in how to control their citizens and demanded reports about criminal behaviour, crime rates prisons and laws. As a result most of the work done in the UK was modest and respected legal principles.

Then WW2 happened and shortly afterwards the modern British welfare state was created. There was a political move towards greater social and economic equality. Coupled with this many great crime researchers came to Britain from Germany where ideas about social demographics and crime were far more advanced. Add into the mixing pot a government and public fear about juvenile delinquents in the 50s and it should come as no surprise that criminology entered the academic arena in 1961 in Cambridge.

Since then criminology has pulled away from a study into how to cure/correct a criminal towards a more interdisciplinary subject concerned with social, philosophical and psychological aspects of crime.

Research questions and chosen disciplines no comments

Hello! Sorry for the tardiness of my first post.

My research questions are (currently):

How can we make an effective mathematical model of the web? How can we make an effective mathematical model of social networking sites? How can we best use these models to “understand” the web and how people use the web?

These questions are rather vague and hopefully they will be refined over the next four years.

In order to make such a mathematical model we must decide what basic properties the model should have. This argument appears circular, needing to know properties of the web in order to make a model which will inform us of properties of the web! However, we are really investigating the (sometimes hidden) effects of these known properties and what they mean for the web.

For example we might want to model Facebook. We could associate Facebook with a graph G by assigning people to nodes and then draw an arc between two people if they are friends. Since it has been shown that two people with mutual friends are more likely to be friends themselves than two people with no mutual friends, one property of G is that it has an abundance of triangles. This means that if node A is joined to node C and node B is joined to node C then it is likely that node A is joined to node B.

In practice drawing G would be virtually impossible because Facebook changes constantly as new friendships are created and destroyed and people join and leave Facebook we make a model graph M (a more convenient graph which we generate and can control). In order to be a good model M must have an abundance of triangles.

Note that the seemingly abstract mathematical property, an abundance of triangles, comes about for a sociological reason. What other properties should the model graph have? To find this out it will be vital to understand how people use the web, so I have chosen to study sociology/philosophy as my first discipline.

Such mathematical models could be used to find the most efficient route from node to node (in the Facebook example from one person to another and be useful at looking at the spreading of ideas). These models could also be used to measure the resilience of a network from attack, (i.e. how will a network cope if we knock out some nodes?) hence I have chosen criminology as my second discipline.

Researching Distributed Currencies no comments

Researching Distributed Currencies.

Over the course of my time here studying Web Science, I would like to do some in depth research into distributed currencies. A distributed currency is a form of money with no centralized processor or controlling authority. At the moment there are only a handful of distributed currencies in existence, and the majority of them stem from Bitcoin. Bitcoin is a “totally” anonymous and distributed online currency. It’s similar to PayPal in that you can use it to buy things online and send/receive currency quickly and conveniently.

PayPal is the opposite of a distributed currency, it’s centralized. PayPal handle all the processing of transactions, and they are also the authority for all transactions and for this service they charge a small fee on each transaction (varying from 2% – 8% of a transaction + a fixed 20p.) If PayPal doesn’t like a transaction, it will slow it, stop it or outright take your money away (googling PayPal took my money returns over 6million results.)

A distributed currency is not centralized. The transaction processing is handled by anybody who chooses to use the currency which normally involves running some client software. Because it’s running on anybodies computer, the currency must be designed in a secure way that doesn’t allow individual clients to tamper with or reverse transactions. The implications of this are a totally unregulated currency where nobody can decide what is right or wrong.

The pro’s of this are that people can make transactions for anything they want, without the worry of their account being frozen or their transaction being blocked or slowed or outright refused by a regulatory authority like PayPal. There is no single point of failure (or corruption.) Also, there is no mandatory fee’s to use these currencies or make transactions. The open distributed nature utilizes the internet in the way it was intended. It could be argued that centralized services governed by one authority undermine the entire point of have the internet (a distributed network) in the first place.

Bitcoin is totally anonymous also. If you want to receive money, you give someone a wallet address. You can have as many wallet addresses as you want which has the end result of it being impossible to link transactions to people. However, combine anonymity, money, and no regulation or authority and sure enough, you get criminals.

Bitcoin received a lot of publicity after the launch of a website called silkroad which was described as “the Amazon marketplace of drugs” which allowed users to by all sorts of illegal items including drugs and weapons – all paid for by the anonymous distributed currency Bitcoin. As well as Silk Road for weapons and drugs, there have also been suggestions that Bitcoin is used to trade in other illicit things such as hiring bot nets, hitmen, slaves, prostitutes and more.

Because there are supposedly a large amount of criminals using Bitcoin, there is a lot of fraud. Browsing Bitcoin forums and it’s not hard to find posts of people frustrated at being scammed out of several hundred Bitcoins (the current conversion is 1btc = $3) because there is no regulatory authority to reverse fraudulent transactions.

However, that’s not to say everyone that uses Bitcoin is a criminal or that every transaction is related to an illegal item. The idea of totally free online transactions should appeal to anybody that sells online, as it could result in lower product prices for the end user.

Over the course of my research, 1 of the many aspects of distributed currencies I would like to look into is ways of making a distributed economy that is less risky to use (e.g. reducing fraud and scams, it maybe that this means reducing anonymity) but maintaining the benefits of free transactions and no single point of failure/corruption.

My 2 subjects of research

My background is in computing science, I think it would be useful for me to also have a better understanding of economics and and criminology for the aspect of research above. Why?:

Economics: wikipedia described economics as “the social science that analyses the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.” I believe a deeper understanding of this and the methods associated with economics would allow me to conduct more informed, appropriate and educated research and to account for and explain the necessity of currency, trade and economies. Specifically I would like to look into online/cyber economics as it’s important to understand the differences (if any) between how people trade online vs. in the real world and how to cater towards these differences and incorporate them into my future research.

Reading Material

I’m not sure yet, I’ve been looking for economics books relating to the web and internet but have been unsuccessful in finding any so far. If anyone has any suggestions, please don’t hesitate to put them forward!

Criminology: wikipedia describes criminology as “the scientific study of the nature extent, causes and control of criminal behaviour in both the individual and in society.” In order to protect something against crime and fraud, I believe it’s important to first understand why people commit crime and fraud in the first place. Specifically I would like to look into cyber criminology to try and get an idea of the research methods used to access and understand such a dark corner of the web. I’d like to learn if and how researchers in this area get full, truthful and honest answers from an area that is inherently full of people willing to mislead.

Reading Material

Not 100% sure on this one yet, but here’s a few ideas:

Cyber Criminology: Exploring Internet Crimes and Criminal Behaviour (2011)

http://www.crcpress.com/product/isbn/9781439829493

“Approaching the topic from a social science perspective, the book explores methods for determining the causes of computer crime.”

Cyber Forensics and Cyber Crime: An Introduction (2008)

http://www.amazon.com/Computer-Forensics-Cyber-Crime-Introduction/dp/0132447495/

“It includes and exhaustive discussion of legal and social issues, fully defines computer crime…provides a comprehensive analysis of current case law, constitutional challenges and government legislation”

Cybercrime from a criminologist and psychological perspective no comments

The growth of the Internet presents a series of new challenges to both individuals and society as a whole. Cybercrime refers to an array of diverse, illegal, illicit activities that all share one thing in common – the environment in which they take place – ‘cyberspace.’

After much consideration the two disciplines that I have decided to examine are Criminology and Psychology. After exploring the underlying principles of both these disciplines, I hope to conclude whether they support each other or conflict with regards to the issue of cybercrime. Similarly, I will also take into account the challenges that cybercrime presents to each discipline, and conclude whether these perspectives offer any solutions to the problem.

As these are both disciplines I have never studied before I am going to look at reading undergraduate text books and basic introductory books as recommended by my peers. I have decided to start my research on criminology by reading the following books:

The Oxford Handbook of Criminology by Mike Maguire, Rod Morgan, and Robert Reiner

An Introduction to Criminological Theory by Roger Hopkins Burke.

For the physiology part of my review I am going to be using the books listed below:

Basic Psychology by Henry Gleitman et al.

The Psychology of the Internet by Patricia Wallace

Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behaviour by Dennis Coon and John Mitterer

I have also come across the following book which I will use to do some background reading on the issue of cybercrime :

Cybercrime and Society by Majid Yar

Easter Reading – Fourth Post no comments

I have now focused the areas of my research to question how the Web has had an impact on ‘Gender’ (Sociology) and ‘Crime’ (Criminology) in respect of identity. I want to observe the two approaches of these disciplines, making comparisons to gain a fuller understanding of how identity is defined and important to academic discussion.

Over Easter I looked at some general textbooks from both disciplines, including:

Giddens, A, ‘Sociology: Introductory Readings,’ (Polity Press, Cambridge, 1997)

Giddens, A, ‘Sociology,’ (Polity Press, Cambridge, 2006)

Morrison, W, ‘Theoretical Criminology,’ (Cavendish Publishing, London, 1995)

Maguire, M, Morgan, R. and Reiner, R, ‘The Oxford Handbook of Criminology,’ (OUP, Oxford, 2007)

From these textbooks I centred my Sociology reading on the theories behind ‘Gender’ and for Criminology I did the same, looking at the role of identity in crime. I hope by examining the theory behind my research questions in the offline World, I can build on them to better understand how the Web may have impacted on these areas.

Media made criminality (4th post) no comments

Two competing anxieties can be discerned in public debate and both are reflected in a large research literature. On the one hand the media are often seen as fundamentally subversive threat to law, on the other as a more or less subtle form of social control. Some researchers tacitly imply that media images of crime do not have significant implications because the establishment of the causal relationship between images and effects is too complicated.

Content of media images of crime

Deviant news

Richard Ericsson and his colleagues: their concern was “social deviance and how journalists participate in defining and shaping it”. Deviance in its broadest meaning, can be defined as “the behaviour of a thing or person that strays from the normal…not only..criminal acts, but also..straying from organisational procedures and violations of common-sense knowledge”. More importantly, deviance is the essence of news and which journalists consider newsworthy. It can also be questioned on what is included in common-sense knowledge which directly affects the representation of crime reported.

Ericsson et al. also found that “popular” media focused overwhelmingly more often on “interpersonal” conflicts and deviance, but “quality” ones included many items on such official deviance as rights violations, or on policy debates about criminal justice or corporate conduct.

The pattern of crime news

Content analyses have found systematic differences between the pattern of offences, victims, and offenders represented by the news and in official crime statistics or crime surveys. Whilst statistics and surveys may represent the “real” world of crime, they are open for interpretation, depending on the context.

An implicit assumption that the gap between media representations of crime and the actuality supposedly disclosed by official statistics causes significant problems – they are accused of exaggerating the risks of crime, cultivating an image of the world that is “scary” and “mean”.

Fear of crime and the coping strategies it leads to (such as not venturing out at night) are deemed disproportionate to the actual risks, and thus irrational and problematic in themselves (Sparks 1992).

—

Success of police and criminal justice: there is also the exaggeration of police success in clearing-up crime (resulting largely from Press reliance on police sources for stories). Summed up in a review of fifty-six content analyses in fifteen different countries between 1960 and 1988, “the over-representation of violent crime stories was advantageous to the police…because the police are more successful in solving violent crimes than property crimes”. The media generally present a very positive image of the success and integrity of the police and criminal justice more generally.

—

Characteristics of offender: there is a clear pattern to news media portrayal of the characteristics of offenders and victims. Most studies find that offenders featuring in news reports are typically older and higher-status offenders than those processed by the criminal justice system.

Characteristics of victims: there is a clear trend for victims to become the pivotal focus of news stories in the last three decades. This parallels the increasing centrality of victims in criminal justice and criminology. News stories exaggerate the risks faced by higher status, white, female adults of becoming victims of crime, although child victims do feature prominently. The most common victims of violence according to official crime statistics and victim surveys are poor, young, black males. However, they figure in news reporting predominantly as perpetrators.

There is a predominance of stories about criminal incidents, rather than analyses of crime patterns or the possible causes of crime. There is a concentration of events rather than exploration of the underlying causes. As summed up in one survey of the literature, “crime stories in news papers consist primarily of belief accounts of discrete events, with few details and little background material. There are very few attempts to discuss causes of or remedies for crime or to put the problem of crime into a larger perspective”.

Content of crime fiction

Frequency of crime fiction: while there have been important changes over time in how crime is represented in fictional narratives, crime stories have always been a prominent part of popular entertainment, usually accounting for about 25% of output.

The pattern of crime in fiction

While crime fiction presents property crime less frequently than the reality suggested by crime statistics, the crimes it portrays are far more serious than most recorded offences.

The clear-up rate is also high in fictional crime. Overwhelmingly majority of crimes are cleared up by the police but an increasing majority where they fail.

Consequences of media images of crime

Most research has sought to measure two possible consequences of media representations: criminal behaviour (especially violence) and fear of crime.

There are several logically necessary preconditions for a crime to occur and the media play a part in each of these, thus can affect levels of crime in a variety of ways. The preconditions are as follows:

- Labelling: for an act to be labelled as “criminal”, the act has to be perceived as “criminal” by the citizens and the law enforcement officers. The media plays an important role in shaping the conceptual boundaries and recorded volumes of crime. The role of the media in helping to develop new (and erode old) categories of crime has been emphasised in most classic studies of shifting boundaries of criminal law within the “labelling” tradition. The media shape the boundaries of deviance and criminality, by creating new categories of offence, or changing the perceptions and sensitivities, leading to fluctuations in apparent crime.

- Motive:

- Social anomie theory: the media are pivotal in presenting for universal emulation images of affluent life-styles, which accentuate relative deprivation and generate pressures to acquire ever higher levels of material success regardless of the legitimacy of the means used.

- Psychological theory: it has been claimed that the images of crime and violence presented by the media are a form of social learning, and may encourage crime by imitation or arousal effects. It has also been argued that the media erode internalised control by desensitisation through witnessing repeated representations of deviance.

- Means: it has been alleged that the media act as an open university of crime, spreading knowledge of criminal techniques. However, the evidence available to support this allegation remains weak.

- Opportunity: the media may increase opportunities to commit offences by contributing to the development of a consumerist ethos. The domestic hardware/software of mass media use e.g. TVs, radios, PCs, have become common targets of property crime and their increase in popularity has been an important aspect of the spread of criminal opportunities.

- The absence of controls: external control – police, law-enforcement officers; internal control – small voice of conscience; both of which may be enough to deter a ready-to-commit offender from offending. A regular recurring theme of respectable anxieties about the consequence of media images of crime is that they erode the efficacy of both external and internal controls. E.g. ridiculing law-enforcement agents, negative representation of criminal justice or potential offender’s perception of the probability of sanctions.

The media and fear of crime

Signoriello (1990): Fearful people are more dependent, more easily manipulated and controlled, more susceptible to deceptively simple, strong, tough measures and hard-line postures – both political and religious. They may accept and even welcome repression if it promises to relieve their insecurities and other anxieties. That is the deeper problem of violence-laden television.

Causes of media images of crime

The immediate source of news content was the ideology of the reporter, personal and professional and this view is supported by most of the earlier studies. However, a variety of organisational and professional imperatives exerted pressure for the production of news with the characteristics identified by content analyses:

- The political ideology of the Press: majority of the press intend to remain politically neutrality. Traditional crime reporters explicitly saw it as their responsibility to present the police and the criminal justice system in as favourable a light as possible. However, the characteristics of crime reporting were more immediately the product of a professional sense of news values rather than any explicitly political ideology.

- The elements of “newsworthiness”: the core elements of “newsworthiness” are: immediacy, dramatisation, personalisation, titillation and novelty (hence, most news are about deviance). This explains the predominant emphasis on violent and sex offences, and the concentration on higher-status offenders and victims, especially celebrities.

- Structural determinants of new-making: e.g. concentrating personnel on courts is economical use of resources but has the consequence of covering cleared-up cases, creating a misleading sense of police effectiveness. The police and criminal justice system control much of the information on which crime reporters rely and this gives them a degree of power as essential accredited sources.

Relevance to cybercrime

Deviance is the essence of news; it is the key virtue that makes something newsworthy. This means that the selection of reported incidents depend heavily on how the media’s definition of deviance. In addition, the success of police, the characteristics of the offender(s) and victim(s) involved in the incident are major factors that affects the amount of coverage an incident will receive in the media.

With regards to cybercrimes, it is interesting to find out the difference between the amount of coverage of cybercrimes in the media and the actual number of incidents in cybercrime statistics. My guess is that cybercrimes are heavily under-reported and the reasons for this under-reporting are made apparent by the findings given above. Cybercrimes are often carried out by more than one offender on a global scale and often anonymous. In some cases, they are carried out by highly-skilled but ordinary looking males (who are usually classified as social excluded or “geeks”) with little valuable newsworthy characteristics. The victims of cybercrimes most often are not aware they have become victims or the impact is so insignificant that it is not newsworthy. In other words, it is hard for the media to find newsworthy stories to tell with regards to the victims of cybercrimes (with the exception of online child offences). In addition, I believe that people are generally not interested in cybercrime-related news items because there is an a-priory assumption that cybercrime issues are too difficult to gain a visualisation in their head, as one would normally see in a picture capturing an act of violence for example.

This part has given me new insights into looking at the failure in promoting awareness of cybercrime in a climate where crime is often exaggerated by the media. Traditional crimes such as theft and violence are often exaggerated to an extent that the level of fear is irrational. Yet, the attitude towards cybercrime is opposite. The level of fear and the precautionary measures in response to the fear is not enough for the average internet users to protect themselves sufficiently. I strongly believe that content analysis of news reports is an important area in the research into raising public awareness to cybercrime.

Contemporary landscapes of crime, order and control (3rd Post) no comments

Source: The Oxford Handbook of Criminology by Maguire. Morgan and Reiner

This week, I have been reading chapter 3 of the book which is on the influential theories behind the governance and control of crime. Changes to the landscape of crime, order and control forces the shape of criminology as a field of study to be revised.

- Which topics command the most serious attention

- Which theoretical resources and empirical materials best advance contemporary analysis

- How to contribute pertinently to public debates on crime and control

Significant features which shifts and changes include:

- Contemporary shifts in the character of the governance of crime

- The changing postures and capacities of the state

- The intensity of public sensibilities towards criminal justice matters

- The shifting boundaries between the public and private realms in providing security

- 5. Social consequences of risk

- The place of crime and social order in public culture

The chapter is divided into three chapters, governance, risk and globalisation, all of which are important factors in our perception of crime today. Below are the notes I have made.

Governance

Governance: blurs the distinction between state and civil society. The state becomes a collection of interorganisational states made up of governmental and societal actors with no sovereign actor able to steer or regulate.

Transformation in the field of control institution and philosophies came in the 1970s when there was:

- Massive escalation in post-war crime rates

- Significant changes in economic, social and cultural relations. Modernity include:

- Transformation in capitalist production and exchange

- Changes in family structure e.g. rising divorce rate

- c. Proliferation of mass media

- A democratization of everyday life – as witnessed in altered relations between men/women parents/children and a marked decline in unthinking adherence towards authority.

- New Rights government rule in USA, Britain, Australia and New Zealand which aimed specifically to break with the economic and social consensus of the post-war decades. The result is the formation of “MARKET SOCIETIES” in which social inequalities deepened and had profound ramifications on levels/responses/politicization of crime.

Refiguring policing and prevention

- De-centering of the criminal justice state: there is a tendency for government officials and senior practitioners to emphasize the limits of the police and criminal justice in controlling crime and to seek to inculcate correspondingly more “realistic” public expectations of what state criminal justice agencies can accomplish.

- Managerialism: subjected the police, courts, probation and prisons to a regime of EFFICIENCY and value-for-money, performance targets and auditing, quality of service and consumer responsiveness. (an attempt to inject “private sector disciplines” into public criminal justice agencies)

- Emergence of crime prevention partnerships at a local level: commercial actors delivering closed-circuit television systems (now: ISP supply data, eCrime police)

Risk

Long standing professional concerns with judgements about ways of anticipating and forestalling future harms have evolved and extended to incorporate new methods, statistical models and the availability of previously unimagined computational power.

The refocusing of the theory and practice of crime control in terms of risk actually serves to reconfigure its objects of attention and intervention, its intellectual and institutional connections with other domains, and its cultural and political salience and sensitivity in potentially fundamental fashion.

Gidden, we live in a world of “manufactured uncertainty” and it is characteristic of such a “risk-climate” that its institutions become reflexive. That is, endlessly monitoring, adjusting and calculating their behaviour in the face of insatiable demands for information and pressures for accountability.

Becks, “Risk may be defined as a systematic way of dealing with hazards and insecurities induced and introduced by modernisation itself. Risks, as opposed to older dangers, are consequences which relate to the threatening force of modernisation and to its globalisation of doubt.”

Globalisation

Relations between states and societies (and the economic and political systems within which they are embedded) have altered in ways that rob analyses of “societies” as distinct entities with clear boundaries of much of their purchase, and bring to the fore the issue of networks and flows; movement of capital, goods, people, symbols and information across formerly separate national contexts.

Criminal networks and cross-border crime flows (transnational crime)

Hirst and Thompson emphasise that globalisation is not a new phenomenon and can be traced back over centuries. However, in terms of the extensity, intensity, velocity and impact of global networks and flows, the globalisation new are witnessing is distinct.

Criminal networks operate ruthless protection and enforcement systems that challenge directly “an essential component of state sovereignty and legitimacy”. Such networks become appealing cultural idols for many dispossessed young males who see no other obvious route out of poverty, as well as having more diffuse effects at the level of popular culture.

Shadow enterprises deploy some variant of bribery, extortion, political funding, assassination or armed combat as a means to undermine the governing capacities and political authority of weak or “failed” stats. Such networks have assumed a key role in setting the basic terms of existence across many parts of the globe. (Most cybercrimes are moving towards organised crime)

“Local” crime and responses to crime

Bauman has written provocatively that the economic precariousness and existential insecurity attendant upon globalisation generals “withdrawal into the safe haven of territoriality” and condensed anxieties about, and social demands for, safety.

Transnational crime control

Interpol was originally set up in 1923 and in its current guise in 1949. However, its impact has diminished because the US is trying to extend and coordinate law enforcement beyond its borders and the building of an enhanced police and criminal justice capacity within the EU.

The developments in the EU are:

- The 1992 Maastricht Treaty of a Third Pillar of EU competence in “justice and home affairs” of forms of intergovernmental activity and supranational policymaking in areas of police cooperation, efforts to tackle organised crime and measures concerning immigration, asylum policy and other matters.

- The onset of institutions, networks and training programmes aimed atfurthering the exchange of information and know-how among Europe’s police officers, prosecutors and judges.

- New modes of ground-level cooperation between national police forces e.g. Europol liaison officers

Relevance to cybercrime

Cybercriminals most often belong to an organisation or criminals across the globe with well structured hierarchies and well organised plans to aggregate profit in a quick, efficient and well disguised manner. This chapter has introduced the theories behind the changes in governance, the influence of risk on society and in particular, it has introduced the impact of globalisation on crime and control. It would be interesting to see if cybercriminals really are those “dispossessed young males who see no other obvious route out of poverty”. It has also introduced transnational policing and some of the developments such as the Europol.