Archive for October, 2013

Web Doomsday: What Will Happen if The Web Just Disappeared? no comments

On an evening two weeks ago, a power-cut in Southampton plunged the city into darkness. As much of the city’s buildings lost power, people started wandering out onto the streets. Despite the power cut lasting no longer than 30 minutes, there was a faint air of panic as everyone was reminded of how much they have come to be dependent on electricity. I was one of them – living in a modern flat, no electricity means no lighting, no cooking facilities and no running water – the basic amenities of modern life.

But I was also reminded that the Web is just as vulnerable. Much like electricity, the web has become something we are dependent on. And like electricity, the complex infrastructure that delivers Internet to our homes is prone to disruption through countless ways. The Southampton power-cut was caused the failure of a single substation. Likewise, the failure of a single point on the Internet infrastructure can cause huge disruption. The reasons may be accidental or malicious.

Above: People walk the streets of New York during the 2003 blackout. It was caused by a software bug and affected 55 million people, lasting almost a day for some and over two for others.

So over the next few weeks, I am going to consider what might happen if the web were to disappear. Given that there is still over half the world’s population to start using the Web, it seems an appropriate time to why this is and whether this impacts their lives. For example, the widespread political issues surrounding web availability, such as restrictive firewalls and censorship, could provide insight into how loss of access to the Web affects us already.

Literature in Social Anthropology can tell us how humans have historically dealt with loss of perceived necessities, whether it be wartime rationing or survival during and after natural disasters. Perhaps this can help us prepare for a disaster that leads to the loss of the web. And if we did lose the Web, what would the impact be? Modern civilisation is governed through Economics, which, considering how the Web has become a platform for economic prosperity, could be one of the most affected areas.

The uptake of the web is not stopping any time soon, and the loss of the web could be detrimental to a future society. Now is an important time to get a better understanding of what the consequences of loosing the web would be.

Archaeology, crime, and the flow of information. no comments

Whether it be from property developers, civil war and conflict, treasure hunters and local enthusiasts, or just “bad archaeology”, archaeologists and heritage professionals have long struggled with the question of how to ensure the protection of sites, monuments and antiquities for future generations. Archaeological method and “preservation by record” were historically born out of situations where archaeology can not be conserved and within a desire to uphold one of the main principles of stewardship: to create a lasting archive. As archaeology is (very generally speaking) a destructive process that can not be repeated, an archive of information regarding the context and provenance of archaeological sites and finds is created to allow future generations to ask questions about past peoples.

Recent years have presented numerous ethical challenges to archaeologists and and other stewards of the past, particularly where crime and illicit antiquities are concerned. Social media and web technologies in general have provided, in some cases, real-time windows into the rate of the destruction of heritage sites within areas of war and conflict. Evidence from platforms such as Google Earth, Twitter, and YouTube have all been used by world heritage stewards to plead for the protection of both archaeological sites and “moveable heritage”. Ever-evolving networks of stakeholders in the illegal antiquity trade have also been identified and linked to looted sites in areas where some have hypothesized that the sale of antiquities is actually funding an on-going arms trade in regions consumed by civil war.

Although a case could be made for investigating the nature of archaeology and crime from the angle of many different disciplines (philosophy, ethics, economics, law, psychology, to name a few), criminology and journalism were specifically chosen to offer insight into the role of the Web as a facilitator in the flow of information. Both disciplines are concerned with information flow and resource discovery – for example, in journalism the flow of information between (verifiable) sources of information through to dissemination to the public, and in cybercrime the important information exchange that drives networks of crime (both physical and virtual).

Focusing on the nature of information exchange, what would criminology and journalism contribute to the following topics?

- Social media and the dissemination of heritage destruction. What are the ethical issues surrounding the use of social media sources in documenting heritage destruction? Can/should social media sources (sometimes created for other purposes) be used as documentation to further research or conservation aims within archaeology?

- The international business of selling illicit antiquities – from looters to dealers – what role does the Web play in facilitating these networks of crime? What methods for investigating cybercrime could be applied to the illicit antiquities trade to better understand the issues surrounding provenance?

- Does the “open agenda” and the open data movement specifically (e.g. online gazetteers of archaeological sites, open grey literature reports with site locations, etc.), create a virtual treasure map and subsequently increase the likelihood of looting at archaeological sites?

Some aspects of each discipline which I believe to be relevant to the study of each (as well as the chosen topic):

Criminology and Cybercrime

- What is crime? (“The problem of where.“/”The problem of who.“)

- Policy and law

- Positivism and the origins of criminal activity.

- Digital Forensics

Journalism

- What is Journalism?

- Who are Journalists?

- Ethics and Digital Media Ethics

- Anonymity, Privacy and Source

- Bias and Conflicts of Interest

Some Potential Sources

Criminology:

Burke, R.H., 2005. An Introduction to Criminological Theory: Second Edition. Willan Publishing.

Walklate, S., 2007. Criminology: The Basics. 1st ed, The Basics. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Yar, M., 2013. Cybercrime and Society. 2nd ed., London: SAGE.

Journalism:

Ess, C., 2009. Digital Media Ethics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Frost, C., 2011. Journalism Ethics and Regulation. 3rd ed., Longman.

Harcup, T., 2009. Journalism: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed., SAGE.

Who benefits from MOOCs? no comments

My proposed title for this assignment is ‘Who benefits from MOOCs?’. These ‘Massive Online Open Courses’ have been in the ed/tech news quite a lot recently, and the University of Southampton has also got involved by joining the Open University’s collaborative Future Learn project with a number of other UK universities. Actually, the phenomenon first appeared back in 2008 at a university in a Canada, but in quite a different form to the more well-known courses promoted in some high-profile American universities.

Whatever their (fairly brief) history, these courses have aroused considerable interest in universities, the media, and investors, perhaps because of the number of potential participants (for ‘participants’ read ‘punters’?). Some courses, it seems, have indeed attracted large cohorts of students – an MIT course in electronics registered 155,000 learners last year, though far fewer (around 7,000) actually successfully completed it (Daniel, 2012).

But what can students (whether they complete or not) take away from their experience? Hopefully they learn some interesting things along the way, and possibly make some useful connections with like-minded individuals. However, for those that complete such courses, obtaining certification or formal recognition of achievement is problematic in a number of ways. It is difficult for institutions to ensure the integrity of tests results, and few universities recognise completion of MOOCs in terms of academic credit.

What’s more, designing and implementing online courses is not cheap, quick or easy (even though many optimistic departmental managers seem to imagine that a simple ‘cut and paste’ job on existing face-to-face course materials will do the trick). A key feature of MOOCs is their second ‘o’ for ‘open’ (which entails, according to most commentators, free). To provide meaningful, effective and attractive online courses is not simple (hence Les’ efforts to tap our ideas in recent FoWS lessons?) and yet universities will presumably need to justify the substantial use of resources for their construction.

So, if the completion of a MOOC has questionable value to a student facing university admissions departments or prospective employers, and universities themselves have to invest in their development, but give them away for free, who benefits from MOOCs?

I’d like to approach this question using ideas from economics and philosophy:

Economics

Although economics is often associated with the allocation of resources in business and private enterprise, public goods such as education are significant factors in the models which economists use to understand societies, economies and human activities within them. However, phenomena such as MOOCs constitute a fairly radical shift in the way education might be conducted and delivered (free to users, huge potential cohorts, geographically unconstrained, difficult to certify). This shift raises a number of questions:

- How do these new courses challenge our understanding of supply and demand in higher education?

- Knowledge is “a public good par excellence” (Gupta, 2007), but who should provide the resources to enable such massive and open access to knowledge?

- How might a ‘social cost-benefit analysis’ of MOOCs be effectively conducted in terms of a student cohort which is geographically dispersed across national boundaries?

- In what other ways might the potential economic benefits (or drawbacks) of MOOCs be analysed?

Philosophy:

From the range of sub-fields included within this discipline, I think epistemology and existentialism may provide interesting ways in which to analyse my research question. Epistemology deals with defining knowledge and attempting to understand the ways in which humans can acquire it. It might be interesting to look at the ways in which people perceive and value knowledge which is given away for ‘free’ by universities, as these institutions have previously put conditions and restrictions on student access to the knowledge which universities possess. This idea relates to an important concern in epistemology, namely the sources of knowledge.

From my brief survey of some basic literature, it seems that there is little consensus on a precise definition of existentialism. However, its fundamental concern with the individual, free will, and the individual’s responsibility for their own actions and the consequences of them may have relevance to this subject. It might be interesting to explore an existentialist view on the ways in which individuals can benefit from participation in MOOCs regardless of the (lack of) incentive of accreditation for their achievements – an existentialist might argue that it is enough to participate in such courses sincerely and with passion.

The lack of value placed on participation in or completion of a MOOC (by universities/employers/society more widely) could be seen to be in line with the existentialists’ view of the external world’s ‘indifference’ to individuals – though this does not, for them, necessarily entail any disincentive for an individual to continue striving within an indifferent world.

References

Daniel, J. (2012) Making Sense of MOOCs: Musings in a Maze of Myth, Paradox and Possibility. JIME. 18 pp. 1-20 Available from: http://www-jime.open.ac.uk/jime/issue/view/Perspective-MOOCs [Accessed 12 Oct 2013]

Gupta, D. (2007) Economics – a very short introduction. Oxford: OUP

Temple, C. (2002-2013) Existentialism. Philosophy Index. Available from: http://www.philosophy-index.com/existentialism/ [Accessed 11 Oct 2013]

Temple, C. (2002-2013) Epistemology. Philosophy Index. Available from: http://www.philosophy-index.com/philosophy/epistemology.php [Accessed 11 Oct 2013]

All in agreement? no comments

Issue: How to reach a global consensus on the balance to be struck between the right to freedom of expression and content which should be illegal on the web.

Background

Prior to the web, content classed as ‘undesirable’ (including that classed as antisocial, defamatory, obscene, pornographic, racist, malicious, threatening, abusive, or undesirable religious or political propaganda) could be regulated far more effectively.

1. Because the mediums used to distribute it were easier to control

2. Each jurisdiction could decide, make and enforce their own regulation on how the balance should be struck.

However, in the wake of the web, concerns have erupted surrounding the ease of propagation of content which could be deemed desirable in one jurisdiction and undesirable in another. The ease of accessing information originating from another jurisdiction makes it almost impossible to enforce national laws on a medium that does not recognise national boundaries.

Gaining global consensus as to the standard/ type/ level of content that should be available on the web has proven difficult. Unlike the approach to fraud or hacking, where, despite differences, a consistent philosophy and approach can be seen among jurisdictions, the balance struck between freedom of expression and illegal content varies greatly from one country to another. Certain governments are more sensitive about the expression of some political or religious views and definitions of obscene or pornographic material vary from place to place.

Therefore, how do we harmonise these different views?

Disciplines:

Mathematics

Mathematics is the science which deals with the logic of shape, quantity and arrangement. Many situations can be represented mathematically and many ‘real world problems’ can be solved using mathematical models. I will be looking to critically analyse whether it is possible to use a mathematical model to decide what content should and should not be deemed desirable on the web.

Anthropology

This is the study of humankind. It draws and builds upon knowledge from the social and biological sciences and applies that knowledge to the solution of human problems. I am particularly interested in ‘sociocultural anthropology’ which is the examination social patterns and practices across cultures, with a special interest in how people live in particular places and how they organise, govern, and create meaning. I will be looking to use anthropology to understand why different jurisdictions have different approaches to the regulation of content online and whether this knowledge can be used to understand better where the aforementioned balance should be struck.

Reading List:

Garbarino. Merwyn S. ‘Sociocultural theory in anthropology: a short history’ (1977) New York : Holt, Rinehart and Winston, c1977.

Hannerz U. ‘Anthropology’s World: Life in a twenty-first-century discipline’ (2010) London : Pluto

Haberman R. ‘Mathematical Models: mechanical vibrations, population dynamics, and traffic flow : an introduction to applied mathematics‘ (1998) Philadelphia, Pa. : Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics

Taylor, Alan D ‘Mathematics and politics : strategy, voting, power and proof’ (1995) New York : Springer-Verlag

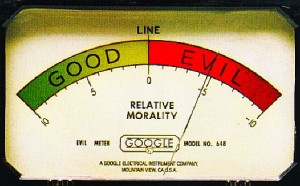

Does the Web make us evil? no comments

The Web provides a unique set of contexts and questions to study a variety of topics. One area where this is particularly evident is our online presence. It is well documented that people’s behaviours are different in an online situation, for instance trolling and hactivism. Whilst these differences are often attributed to the anonymity that the web offers, there are many examples of them manifesting in identifiable circumstances, such as on social networking sites. As a means to focus my research, I will likely concentrate on the activities of people on social networking sites with a view to understanding the behaviour behind them.

This issue of a difference between our online selves and ‘real’ selves can be examined through many different lenses. There are legal aspects to this such as if and how laws are applied on the Web. Economically we can look at the differences between shopping on- and offline. Broadly speaking, these deal with practical concerns relating to online personas. From a more abstract perspective, and underpinning the practical approach, we can question the way we think.

Considering how much of it I purportedly do for a living, until recently I had never given much consideration to understanding the processes behind. A fascinating idea I have come across is the difference between how we think and how we think we think. This is something where psychology and philosophy intertwine.

Psychology

Psychology has always been associated with analysing social issues and behaviours. The psychology of online behaviour is a very broad subject with a great deal of conflicting conclusions. In recent months, an area that has unfortunately come to the fore is the phenomenon of depression and bullying that exists on and via social networking sites, and one of the areas I will look at is the ethics of online behaviour. In particular I am keen on looking into how our morals, or perception of morals, are formed. The reasons behind any disparity between offline and online ethics will provide an insight into this.

Philosophy

Morality is an issue that has been extensively studied from a philosophical perspective. Whilst psychology is useful in examining the reasoning behind a code of conduct, philosophy concerns itself more with the actual code. Various philosophers have attempted to explain what morality is and this provides a more direct approach to understanding its formation. The vast majority of these theories have been developed in the absence of the Web which hence provides a rigorous testing ground for them.

Naively speaking, psychology is the study of how we think whilst philosophy is the study of what we think. Of course, each of these fields can claim to subsume the other ipso facto. Rather than trying to combine these two fields in a hierarchical relation, I will attempt to unite them in a more balanced manner.

The topic of ethics can be viewed as a part of a larger debate into our attitude to socialising on the Web. Depending on the scope of the topic, this is something I will hope to extend to.

Improving Intertwingularity no comments

In the 1987 revision of his book Computer Lib [1], Ted Nelson wrote:

EVERYTHING IS DEEPLY INTERTWINGLED. In an important sense there are no “subjects” at all; there is only all knowledge, since the cross-connections among the myriad topics of this world simply cannot be divided up neatly. Hierarchical and sequential structures, especially popular since Gutenberg, are usually forced and artificial. Intertwingularity is not generally acknowledged—people keep pretending they can make things hierarchical, categorizable and sequential when they can’t.

I’m not sure the Web has yet caught up with Nelson’s vision of Project Xanadu, or the degree to which it is practical to do so. But, he makes a good point about the weakness of relying too much on hierarchy. Hypertext makes possible a wonderfully interconnected Web which has been a daily source of improvement and enjoyment. However, much of it feels like moving around a big box-and-line diagram, merely mapping nodes and links. Frequently, web usage is continuous a loop in and out of search tools (like Google) between individual or small clusters of pages, rather than following richly linked data strands.

Richer linking is less common. Although many links may be present in a document many are simply in-page/site navigation links or SEO-aiding faux page breaks. Also, the paucity and sterility of links may reflect the economic approach of finding and trapping eyeballs – why send people to your competitors, by linking to them? Links to, or through, paywalls are also of suspect value. Meanwhile, given the node-and-link model, we tend to envision the web as hierarchy – or a directed graph at least. A less intertwingled reality, it seems.

My experience from writing documentation and software community support has shown it surprisingly hard to achieve sticky knowledge transfer except when working at or close to one-to-one scope; not very efficient. The lazy reaction is to blame the learners, but I’m open to the thought that as authors of hypertext, maybe we’re not doing this right. Perhaps we need to use a different tack and be less shallow in our weaving of the Web, offering the reader more routes to their goal of knowledge. More intertwingularity, applied with some thought, might move us forward. Approaches like spatial hypertext and techniques from hypertext fiction may help, even if currently egregious compared to standard practice.

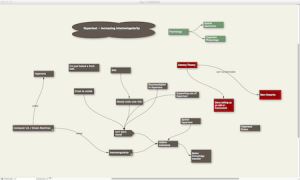

Figure: Early stage planning in Tinderbox

Serendipity strikes, as now I’m being asked to look at a Web issue through the eyes of two different disciplines. Those I’ve selected as showing promise in providing a useful alternative view to the above, are:

- Psychology. This studies the human mind and behaviour, seeking to explain how we feel, act and reason. The intuited relevance to my topic is that a better understanding of our reasoning – and motivation for behaviour – might allow us to make smarter choices about how we author hypertext, to meet and reward those motivations.

- Literary Theory. This discipline seeks to describe the methods and ideas we use in the – reading and understanding of literature. A set of tools, if you will, by which we may understand literature. It will be interesting to see how the non-linearity of Hypertext fiction fits current theory.

I’m unsure as yet how narrow we may set our disciplinary scope here as, within the above, Cognitive Psychology and Narrative seem sensible sub-topics. Within the Literary Theory and indeed Narrative, culturally-based sub-sets with doubtless exist: does one size fit all? However, my plan is to start wide and winnow to find an appropriate breadth of coverage.

Starting Texts

Thus far my research has been a reconnaissance, more browsing than structural study, to help me pick some starting research references. So, these are my selections for initial study at least in terms of published books. Disclosure – I’ve not yet read these, rather they are what I plan to start reading:

- Psychology / G. Neil Martin, Neil R. Carlson, William Buskist.

- Cognitive psychology : a student’s handbook / Michael W. Eysenck, Mark T. Keane.

- Literary theory : a very short introduction / Jonathan Culler

- Literary theory : an introduction / Terry Eagleton

Footnotes:

- [1] Nelson, Theodor (1987), Computer Lib/Dream Machines (Rev. ed.), Redmond, WA: Tempus Books of Microsoft Press, ISBN 0-914845-49-7

Title: Impact of Open Trends in the Economy and the Government no comments

Areas: Web-Open Source-Economics, Web-Open Data-Political Science

The Web is a global community in which more disciplines are open to collaborate and incorporate their knowledge. We are living in a world that the tendency to openness is gaining territory. A clear-cut example is the open source and open data trends. I am interested in doing research how these tendencies are developing the web, and how will be their behavior in the next years. Furthermore, I want to know how opening tendencies are related to social areas such as: Economy and Politics, and how these areas are being affected by this trend.

Justification:

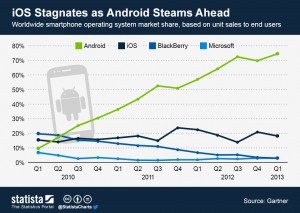

Open source operative systems have become increasingly important specially in smart phones and Servers.

This evidence shows that firms and governments such as: Google, Novell, IBM, Panasonic, Virgin America, CISCO, Amazon, Peugeot, Wikipedia, US department of Defense, US Navy Submarine Fleet, The City of Munich, Germany, Spain, Federal Aviation Administration, French Parliament, State-Owned Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Pakistani School and Collages, Cuba, Macedonia Ministry of Education and Science, U.S. Postal Service, U.S. Federal Courts, Government of Mexico City rely on open source systems to Systematize administrative, operational, and financial processes within the firm, by collecting information that improves rational decision making inside the firm which in turn affects the competitiveness and current profitability as well as future profitability.

For instance, an open source system could be a relatively low cost tool for the firm to collect and systematize data that allows the firm to make better decisions to allocate resources (by facilitating the comparison of suppliers in terms of price and quality), to reduce administrative costs, to improve the process of strategic planning, to improve the market penetration of the firm’s products (by gathering relevant information of the preferences of costumers over the firm’s products). Hence, open source systems are critical for the firm to be competitive and profitable.

Open Data means Better Governments

International institutions such as the World Bank have emphasized the role of governance. Better governance means that the government is willing and capable to better represent the preferences of a majority of individuals in public policies. This means that better governance is related with the willingness and ability of the government to satisfy the needs of a majority (instead of a minority) of their citizen.

Open data is related with the ability of citizen to request information about the activities of the government (such as salaries of public officials, the mechanism for the allocation of public funds to different public programs, access to information about how the government select individuals who benefit from public programs, and so on). Moreover,, open data increases the transparency of the government and accountability which induces the government to better respond to the demands of voters . In other words, open data improves governance.

How is gender equality represented on the web? A Philosophical and Psychological Study. no comments

This isn’t as some might think just an excuse to attack the male gender and point out the sites used to discriminate against females; rather looking at how the web has (in places) facilitated gender divides. There are websites, Facebook groups, forums, etc, set up in the name of promoting one gender over the other. The web (as in many areas such as cyber bullying) given people a safe impersonal place to display their prejudices and explore them with like minded people. Unfortunately it’s much easier to sit there and argue that your gender is superior than fight with both factions to say that everyone is the same. I support this topic and the arguments for it are essentially the same as cyber bullying, racism, ageism or any such discrimination on the web, although I would say that this was more of a grey area, and since it is one of personal interest I have chosen this specific section for my review.

The disciplines I have chosen are psychology and philosophy as I know absolutely nothing about them, and they have some relevance to this issue.

Psychology:

The areas that will be studied here are the basic principles of psychology particularly emphasising on behavioural psychology and why people behave the way they do in relation to gender inequality. Reading will focus on both feminist psychology values (and whether they are actually a set of values geared towards equality or if they are more geared towards female bias), in addition to finding out more about the male psyche. Both of these areas are relevant to the topic as they explore both sides of the coin, and on top of this I will be studying why people find the web an easier medium for their prejudices than face to face; and whether the web has brought out a ‘freer’ element for people to express their opinions, or actually negatively enhanced people’s ability to impersonalise discrimination.

Philosophy:

Philosophy wise, the areas that seem most relevant and interesting to this topic are: firstly, the ultimate question of ‘what is equality’ gender or otherwise, from a philosophical standpoint; secondly an ethical investigation of how equality should be promoted, and what actually counts as discrimination. Philosophy leaves a lot of room for personal interpretation, and so does a lot of the material on the web, where should the line be drawn between a joke and something that is actually a discriminatory comment?

Philosophical Psychological View:

Finally these two disciplines will be looked at together in relation to this issue; hopefully to combine the ethical definitions of equality from a philosophical point of view, with the behavioural psychology points of view to better understand how the web has actually affected gender equality.

Blog Post Plan:

Week 1 (14th Oct) – Intro

Week 2 (21st Oct) – Philosophy 1 – Defining Equality & Arguments against Equality

Week 3 (28th Oct) – Psychology 1 – Methodology of Psychology

Week 4 (4th Nov) – Philosophy 2 – Methodology of Philosophy

Week 5 (11 Nov) – Psychology 2 – Defining Gender & A Gender View of the Web

Week 6 (18 Nov) – Philosophy 3 – Key Question: What defines an gender equal web in terms of philosophy?

Week 7 (25 Nov) – Psychology 3 – Key Question: What defines an gender equal web in terms of psychology?

Week 8 (2nd Dec) – Philosophy 4 – Philosophical Conclusions

Week 9 (9th Dec) – Psychology 4 – Psychological Conclusions

Week 10 (16th Dec) – Philosophy of Psychology

“Is it safe to drink the water?” no comments

How many people carry matches these days?/Susan Sermoneta ©2012/CC BY 2.0

Question

How can corporations be encouraged to open their data (so that we know it’s safe to drink the water)?

Background

The benefits to corporations of opening their data is well documented, but they are not necessarily appreciated in all sectors of industry.

Prospecting for oil and gas with the aim of engaging in hydraulic fracturing (‘fracking’) operations causes some popular concern which could be alleviated by the more open availability of real-time monitoring data.

In the UK, all industrial activities are subject to health and safety audits and some involve continuous, around the clock monitoring. For example Cuadrilla Resources employ Ground Gas Solutions to provide 24 hour monitoring of their explorations in the UK. Ground Gas Solutions monitoring aim to:

provide confidence to regulators, local communities and interested third parties that no environmental damage has occurred. (GGS, 2013)

Currently the data collected through this monitoring is made public via reports to regulation authorities, which can be subject to significant delay, are often written in technical language, and are not easily accessed by the general public.

My argument is that real time (or close to real time) monitoring data could be made open without any damage to the commercial advantage of the companies involved, and, if clearly and unambiguously presented (e.g. via a mobile app), could go some way to alleviating public concerns, particularly regarding the possible contamination of drinking water. Exploring what motivates some corporations to make their data open and the challenges they have overcome to do this, may suggest successful strategies for encouraging proactive, open behaviour within industry.

Disciplines

Anthropology – Considers key aspects of social life – identity, culture, rationality, ethnicity and belief systems.

Anthropologists aim to achieve a richness in the description of encounters they have with people and places, and have a strong tradition of creating narratives and developing theories that describe and attempt to explain human behaviour. In the context of the exploration industry, how might an anthropologist explore the underlying cultural values and prevalent beliefs of people working within corporations?

I believe that exploring this issue through the lens of anthropology would provide some insight into the workings of the energy exploration business and uncover useful data that may indicate strategies for encouraging corporations to share real time monitoring data.

Economics – Analyses the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

The widespread use of empirical data related to economic exchange together with emerging theories of human behaviour appear to underpin this discipline, which I believe have significant value to the study of my question. Exploring the commercial incentives for opening real time monitoring data from the perspective of differing economic theories combined with the data collection methodologies prevalent within this discipline can provide useful understandings of the question, which may point to practical solutions.

Anthropological Economics: an interdisciplinary approach

The question: “How can corporations be encouraged to open their data?” appears to call for solutions that tackle not simply the “bottom line” of economic necessity, but also the culture that requires individuals within corporations to maintain secrecy in order to maintain or improve their employers market position. From my current naive standpoint, a combination of the anthropologists qualitative, narrative-driven approach to studying human behaviour with the economists quantitative, theory-dominated view of commercial interaction looks like a worthwhile approach to gaining a better understanding of the key issues.

Proposed reading list

Anthropology:

Eriksen, T. H., 2004. What is Anthropology? London: Pluto Press.

Eriksen, T. H., 2001. Small Places, Large Issues: An Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology. London: Pluto Press.

Fife, W., 2005. Doing Fieldwork. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Miller, D. ed., 1995. Acknowledging Consumption. London: Routledge.

Economics:

Fogel, R. W., Fogel, E. M., Guglielmo, M. and Grotte, N., 2013. Political Arithmetic : Simon Kuznets and the Empirical Tradition in Economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Giudici, P. and Figini, S., 2009. Applied Data Mining for Business and Industry. London: Wiley.

Isaac, R. M. and Norton, D. A., 2011. Research in Experimental Economics: Experiments on Energy, The Environment, and Sustainability Governance in the Business Environment. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Quiggin, J., 2011. Zombie Economics: How Dead Ideas Still Walk Among Us. Woodstock: Princeton University Press.

Understanding sharing – ‘Viral’ media sharing across social networks no comments

As a linguist, the way in which material can be shared internationally between various linguistic groups is something I find fascinating. To take a particular example, let’s use ‘Gangnam Style’ – A song with Korean lyrics. Korean is, at the risk of sounding harsh, not the most widely spoken of languages. Consider that of its 75 million native speakers (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_Language), many live in North Korea and would have had no access to the song. On a more linguistic level, Korean belongs to the Altaic language family and is, according to what can be described as a ‘best linguistic guess’, most closely related to Japanese. But I can assure you now that not only do the speakers of the two languages have some long running disputes, but they also don’t understand each other at all. As a speaker of Japanese, I can assure anyone reading this that the languages are not even slightly similar.

So not that many people world-wide would understand the song. And yet its Youtube video has 1,788,916,808 views. (youtube.com/watch?v=9bZkp7q19f0). In the time it took me to type that out, it has probably grown again. And according to Laura Edwards, that’s for one simple reason – Social media sharing, or as she puts it people wanting “their friends, family and distant acquaintances to…share in the enjoyment of” the video. (socialmediatoday.com/laurahelen/980476/how-did-gangnam-style-go-viral)

There are thousands upon thousands of other examples – Youtube videos like ‘Will it Blend?’, memes, songs, adverts…But why DO things go viral? And how do they spread?

With these questions in mind, I’ve chosen the following disciplines: Complexity Science and Psychology. And the reasons for that are simple: Complexity Science deals with complex systems – understanding that system by modelling it and seeking to understand how it works. And is there any system more complicated than a social network? Someone’s sharing something with one group while possibly hiding it from another group – Nobody wants their grandma to see how drunk they were last night.

Psychology, on the other hand, seeks to understand the individual. And the individual users are just as important, in this case. Consider a user X. He sees the Gangnam Style video and does not think it’s funny – He doesn’t share it. Consider a different user, Y – He hears the Gangnam Style song and has an obsession with K-Rap, so he finds the video and shares it everywhere without even seeing it. Understanding these ideosyncrasies is the forte of Psychology, making it ideal for this purpose.

To start with, I’ve already read the Wikipedia entries for Complexity Science (Which redirects to Complex Systems) and Pyschology, spoken to friends studying for postgraduate qualifications in both fields and read “Psychology – A Very Short Introduction” (Butler, G & McManus, F; 1998; Oxford University Press), as well as various Internet articles which seek to define the two disciplines. This was predominantly to confirm my choices than to seek to define them.

As far as further study goes, I’m hoping that the friends I’ve spoken to will provide me with a list of useful materials soon, but in the meantime I’m going to start on Pyschology as it’s more familiar – Linguistics shares some similar concepts. So particularly useful sources that I’ve found so far are “The Analysis of Mind,” by Bertrand Russell, available online from the library, a book called “Approaching Multivariate Analysis: An Introduction for psychology,” which I’m hoping might help me begin to understand how Psychology seeks to ‘solve’ problems and “Atkinson & Hilgard’s introduction to psychology,” all of which are seemingly relevant books I’ve found on Webcat.

With regard to Complexity Science, I’ve come up with the following sources: Chaos Under Control (Peak, David) which seems to give a basic overview of how Complexity Science seeks to cope with ‘chaos’, which seems useful for a social network; Morowitz’s “The Emergence of Everything – How the World Became Complex,” which is an electronic resource which doesn’t seem 100% helpful but I’m reading anyway to get in the ‘complexity mindset’; the Journal of Systems Science and Complexity, which I’m reading just to look at how complexity science is applied and how it ‘solves’ problems.

In addition, I’ve got a lot of Google search result links. I’m working my way through them, but they mostly concern introductions to the relevant disciplines and subfields, such as ‘Internet Psychology’, which seems particularly useful – Who knows: Maybe psychology will turn out to be too broad and I’ll go for that one?

So that’s all for now. Back to reading, I guess