Archive for December 1st, 2010

Identity (Post 5 – More Anthropological Views) no comments

This post will hopefully conclude the final underlying principles and theories of Anthropology, as described in Small Places, Large Issues. These latest concepts have centred on social systems and social structures, with the two being distinguished as:

- Social Systems: Sets of relationships between actors;

- Social Structures: The totality of standardised relationships in a society.

This definition of social systems relates to social networks – the relationships from a particular person, and the scale of these networks has to be considered in contemporary Anthropology as the Internet has meant that non-localised networks are of increasing importance compared to the traditionally studied small-scale societies. Rather than simply focusing on online research to study these networks, however, anthropology stresses an importance of collecting other forms of data: specifically on relationships between online activities, and other, offline, social activities. By doing this, it has been shown that the Internet/Web can surprisingly enhance people’s national and even religious identity, with the example of Trinidadians whose offline and online activities form a single entity – their identity does not seem to be being altered by the Web.

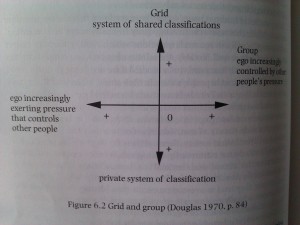

Grid and Group Classification of Societies - from "Small Places, Large Issues: An Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology" Second Edition, by Thomas Hylland Eriksen, page 82.

The above image displays a classification system for societies that focuses on social control. The “Group” axis classifies societies according to their social cohesion, and “Grid” on the shared knowledge in a society. A strong grid, strong group society is explained as a strictly conformist society where an individual’s identity is constructed through the public system of rights and duties. The measures on this grid can help to explain how the identity of individuals in certain societies is shaped through the social control exerted by the social system itself. A typical industrial society could fall in the weak group, weak grid sector (although they can be spread out over the graph), where members are “individualistic and anonymous, and thus others exert little social control over ego” (page 83). A counter argument is that the influence of the state on a society means that they should fall into “Strong group”, so the variation in opinions here is vast and the classifications all seem uncertain and unreliable. It appears to have more value when classifying one particular society, rather than a group such as “industrial society” which is far too vague.

There are differing schools of thought that cover the link between society and individual actors:

- Individualist thought, associated with Max Weber where anthropologists try to find out what makes people do what they do

- Collectivist thought, associated with Marx and Durkhein where anthropologists are more concerned with how society works.

Theories that focus on the actor emerged to critique structural-functionalist models in the 1950s. In these models, the individual was mainly looked over, with focus instead on social institutions. This was criticised, as it was not clear how a society could have needs and aims, and because society can only exist because of interaction – this implies that social norms must be seen as a result of interaction, and not the cause. The author summarises by stating that while structural functionalism seeks to explain cultural variation, it only succeeds in describing interrelationships.

Finally, it is described how Bourdieu examined the relationship between reflexivity or self-consciousness, action and society, resulting in a theory of “culturally conditioned agency”. “Habitus” is the term used by Bourdieu to describe “embodied culture” which enforces limitations on thought when choosing an action, and ensures that “the socially constructed world appears as natural” (page 91). This raises the question of how much of what we do and who we are is just down to habits, conventions and norms imposed on us by the society we are born in to?

As the subject matter of the book is now beginning to move away from the core anthropological theories and on to more specialised areas I will start to focus my reading on specific chapters relating to Identity to build up my knowledge of this area, before moving onto some introductory psychology texts.

Ecology no comments

For the past couple of weeks I have been reading about Ecology, primarily from “First Ecology” (Beeby, Brennan. 2ed 2004).

The book says that “Ecology is the science that seeks to describe and explain the relationship between living organisms and their environment” and the study of “the mechanisms by which species evolve, flourish and disappear.”

Interactions between species are an important aspect of ecology. Interactions are driven by the need for organisms to acquire resources, and could be co-operative, competitive or otherwise. Collaboration between people on the web could be seen as analogous to a co-operative ecological interaction.

Organisms need resources in order to survive; these resources might include water, food, sunlight (for organisms that photosynthesise) or simply space. Competition for resources is at the heart of evolution, since the organisms best suited to their environment (and hence best at harnessing the available resources) are more likely to survive. However, it is not enough for an organism simply to survive, in order to be truly successful it must pass its own genetic information on, through reproduction. We can, therefore, think of the protection and transmission of its own genetic information as being the “goal” of any given organism. Such transmission is itself a crucial part of the evolutionary process.

To achieve this goal, species have developed a huge range of strategies; from fast reproduction that can monopolise a resource, to complex colonies with thousands of individual organisms that share much of their genetic information, to highly-specialised inter-species dependencies, some of which are mutually beneficial and others which are parasitic.

Complexity is an inherent part of ecology. The environment and organisms that live in it are highly interconnected, which poses similar problems to those faced by sociology and web science (as previously discussed). I’ve started looking into how Ecology deals with this complexity, but that’s another post. I also want to look into symbiosis and other highly-cooperative interactions.