Miss Sara Burgerhart’s English guittar

Congratulations to postgraduate researcher Jelma van Amersfoort on her article, “Miss Sara Burgerhart’s English guittar: The ‘guitarre Angloise’ in Enlightenment Holland,” published in the most recent issue of the Tijdschrift van de Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis (TVNM), the journal of the Royal Society for Music History of the Netherlands. Jelma explains the project:

My initial interest in the English guittar was as a musician: three years ago I met London lutenist Taro Takeuchi who let me try his antique (18th century!) wire-strung English guittars by makers Preston and Gibson. As a classical guitarist and lutenist I was fascinated by the sound that wire strings can produce when plucked with the fingertips. After I found out that there is a huge amount of repertoire for the instrument – much of it song accompaniment – I became interested in finding one for myself. Technically and stylistically that was not such a giant leap for me, as I had been specialising in 19th-century guitars and song accompaniment for a long time. Another friend and colleague from the small world of early guitars, Rob MacKillop, then helped me find an affordable instrument, an original Preston from about 1770 in good condition, and on that instrument I taught myself to play.

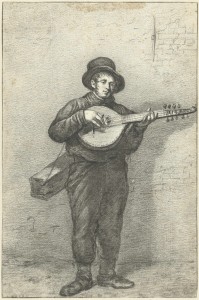

After becoming reasonable competent on the instrument, I wanted to find out if the wire strung ‘guittar’ had been played at all in the Netherlands while it was popular in Britain (ca. 1750-1810). Through examining historic newspaper adverts, iconography and music collections I soon found that it had been played in the Netherlands, both at homes and in public concerts. I also was lucky enough to find scores for English guittar by an Amsterdam composer too, and drawings and engraving by Dutch artists depicting guittars and guittar players. I found it quite surprising that no-one had done much research into this subject.

When you look at it as an organologist (a musical instruments specialist), an ‘English guittar’ is not really a guitar, but rather an 18th century cittern. It has 10 metal strings grouped into 6 courses (four doubles, two singles), and is tuned to c-e-g-c’-e’-g’, a C major chord. The effect is that even if you have just started learning the instrument, it will immediately sound very pleasant and musical. It was called a guitar or ‘guittar’ in its time however, not a cittern, and was used for similar repertoire as the Spanish (gut strung) guitar that was also used: solo pieces, song accompaniment and chamber music in small ensembles. Apart from its tuning, the instrument also differs from modern guitars in its size: it is considerably smaller, and comes in all sorts of shapes: pears, teardrops and almonds.

In Britain a lot of music was printed for the English guittar: simple song settings, Scottish songs and reels, hymns and arrangements of opera arias. Some more ambitious music also saw the light: composer and violinist Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762) composed intriguing sonatas for guittar and basso continuo, and lesser-know composers like Frederic Schuman and Giovanni Battista Marella contributed works in that vein too. Besides that, there are duets for two English guittars, and there is other chamber music.

As to who played the English guittar, we know that in Britain it was mostly played by women of the middle and upper classes, in domestic settings. I am not so sure that the same is true in the Netherlands: I found several mentions of men playing it, both at home and in public. What Britain and the Netherlands had in common though was that most guittar teachers were men, and foreign: Geminiani and Straube in London, and the Frenchmen Dupré and Darme in the Netherlands, for instance.

When searching Dutch books of the 18th century for various guit(t)ars I found all sorts of interesting mentions, both in non-fiction works and in novels. The most striking find –- and also slightly embarrassing because in fact I had read the book when I was in school –- was what is almost certainly an English guittar in the novel Historie van Mejuffrouw Sara Burgerhart (‘History of Miss Sara Burgerhart’), written in 1782 by Elizabeth Wolff and Agatha Deken. Now this was very exciting, because within Dutch culture Sara Burgerhart is extremely important: it is the first Dutch book that really qualifies as a novel; it is written by two women, and it somehow manages to expresses the values of the Dutch version of Enlightenment thinking while being highly entertaining at the same time.

The story of the novel is about the wealthy young Sara, who after losing her parents is raised by a bigoted aunt in a hypocritical and intolerant protestant cult. She runs away and moves to a respectable ladies’ boarding house with a more enlightened atmosphere. Sara sings, plays the keyboard and the guittar. A number of adventures follow, involving more and less desirable friendships and suitors, and Sara gradually learns to make the right choices, based on experience, reason and common sense. At a number of key points in the novel the protagonists play instruments and sing, and the characters appear to have been dealt instruments that serve as metaphors for their personality. The music they play can sometimes be identified as existing works: at one party an Air is sung by Garrick that was set to music by Thomas Arne. The novel ends when Sara – inevitably – marries and starts a family.

The book, an epistolary novel, was an instant success, and was translated into French in 1787. Its preface is directed at the ‘Nederlandsche Juffers!’ (‘Dutch Young Ladies!’) who were the intended readers, and it refers to Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Alexander Pope’s novel The Rape of the Lock (1712). The book itself is on several levels reminiscent of Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa (1748). These references demonstrate the cosmopolitanism of the authors (and of their intended young female readers) and indicates the origin of some of their ideas. The important role that music plays in the novel, and the obvious knowledgeability of the writers in that field has not been noticed much by scholars so far.

So that is why I named my article ‘Miss Sara Burgerhart’s English Guittar. The ‘guitarre Angloise’ in Enlightenment Holland’. I knew that by mentioning Sara Burgerhart, a fictional character that is still very familiar and recognisable to the well-read Dutch, I would make my readers see the connection between the English guittar and Dutch Enlightenment values.