Archive for the ‘Management’ tag

Management Models no comments

Last week I wrote about an introduction to the basic concepts and perspectives in the discipline of management promising a review of some management models this week. This is a summary of Boddy’s second chapter ‘Models of Management’.

Boddy defines a model as aiming to ‘identify the main variables in a situation, and the relationships between them: the more accurately they do so, the more accurate they are.’ A model furthermore provides a ‘mental toolkit to deal consciously with a situation’. Boddy emphasise that managers can draw upon different models according to the varied situations they face – what is important is understanding the values embodied in the model or theory and act accordingly. That is also known as thinking critically about a situation, an essential skill in management.

Boddy and others identify four key types of models of management according to their underlying philosophies:

- rational goal

- internal process

- human relations

- open systems

Rational goal models

Some of the first kinds of models to have been developed, their origins are found in the formation of the modern firm, during the Industrial Revolution, where managers were face with the need to manage new organisational structure profitably. It evolved from the tradition of scientific management and operational research. The model emphasise the aim of maximising output/profit through enhanced control and quantitative information as a basis for decision-making.

Internal process models

These come from the Weberian bureaucratic management ideas and from Henri Fayol’s notion of ‘administrative management’ which emphasise rules and regulations over personal preferences, division of labour and hierarchical structure. While the concept of bureaucracy has been widely criticised (notably for stifling creativity) it has been supported when it allows employees to master their tasks therefore enhancing security and stability and is still widely used today, notably in the public sector.

Human relations models

These theories were developed when experiments on working conditions (lighting or other material factors) produced unexpected results. It was shown that altering the environment positively or negatively, output from the experimental team still increased. Elton Mayo, invited to comment on the results, asserted that output growth was the result of the new social relations established in the team. Individuals felt special, they were asked for their opinion, and as part of the experiment fully collaborated with one another. This led theorists to emphasise the importance of social processes at work, including the well-being of employees.

Open systems

Finally open systems models where the organisation is seen ‘not as a system but as an open system’, which interacts with its environment. Resources are imported, undergo transformations and turned into output that generate profit. Information about the performance of the system goes back as a feedback loop into the inputs. Important variants include socio-technical systems where outcome depends on the interaction of technical and social subsystems. Another is the notion of contingency management which emphasises the need for adaptability to the external environment. And finally complexity theory which focuses on the complex systems, their dynamics and feedback loops where agents within the system interact autonomously through emergent rules. These emphasise the non-linearity of change in organisations.

The table below provides a summary of the four models (from Boddy 2010, p. 61).

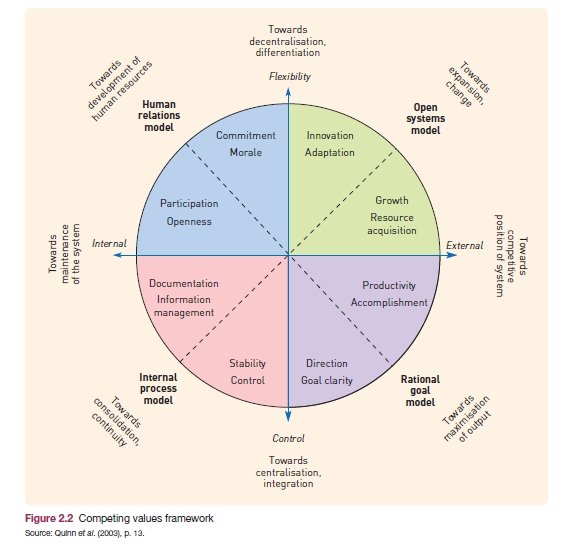

In fact management theorists Quinn et. al. (2003) believe that the four successive models of managements complement rather than contradict each other, and they provide a framework that integrates these various model – the ‘competing values framework

Next week I will look to read about management and global issues to get a better grasp of the discipline’s approach to an issue that transcends its main ontological actor – the organisation.

References

Boddy D. (2010) Management: An Introduction, 5th edition, Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall

Quinn, R.E., Faerman, S.R., Thompson, M.P. amd McGrath, M.R. (2003) Becoming a Master Manager: A Competency Framework, 3rd ed., Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons

Anthropology – approaches and methodologies no comments

Picking up where I left off last week, I will now present the different approaches and methodologies of anthropology as a discipline.

We have already seen that social and cultural anthropology – also known as ethnography – as a discipline endeavours to answer the questions of what is unique about human beings, or how are social groups formed, etc. This clearly overlaps with many other social sciences. For all the authors reviewed, what distinguishes anthropology from other social sciences is not the subject studied, but the discipline’s approach to it. For Peoples and Bailey (2000, pp. 1 and 8), anthropological approach to its subject is threefold:

- Holistic

- Comparative

- Relativistic

The holistic perspective means that ‘no single aspect of human culture can be understood unless its relations to other aspects of the culture are explored’. It means anthropologists are looking for connections between facts or elements, striving to understand parts in the context of the whole.

The comparative approach, for Peoples and Bailey (2000, p. 8) implies that general theories about humans, societies or cultures must be tested comparatively- ie that they are ‘likely to be mistaken unless they take into account the full range of cultural diversity’ (Peoples & Bailey 2000, p. 8).

Finally the relativistic perspective means that for anthropologists no culture is inherently superior or inferior to any other. In other words, anthropologists try not to evaluate the behaviour of members of other cultures by the values and standards of their own. This is a crucial point which can be a great source of debate when studying global issues, such as the topic we will discuss on the global digital divide. And it is why I will spend one more week reviewing literature on anthropology before moving on to the other discipline of management – to see how anthropology is general applied to more global contexts. I will then try to provide a discussion on the issues engendered by the approaches detailed above.

So for Peoples and Bailey these three approaches are what distinguish anthropology from most other social sciences. For Monaghan and Just, the methodology of anthropology is its most distinguishable feature. Indeed they emphasise fieldwork – or ethnography – as what differentiates anthropology from other social sciences (Monaghan & Just 200, pp. 1-2). For them ‘participant observation’ is ‘based on the simple idea that in order to understand what people are up to, it is best to observe them by interacting intimately over a longer period of time’ (2000, p. 13). Interview is therefore the main technique to elicit and record data (Monaghan & Just 2000, p. 23). This methodological discussion is similarly found in Peoples & Bailey and Eriksen (2010, p.4) defines anthropology as ‘the comparative study of cultural and social life. Its most important method is participant observation, which consists in lengthy fieldwork in a specific social setting’. This particular methodology also poses the issues of objectivity, involvement or even advocacy. I will address these next week after further readings on anthropological perspectives in global issues, trying to assess the tensions between the global and particular, the universal and relative and where normative endeavour stand among all these.

References

Eriksen, T. H. (2010) Small Places, Large Issues: An Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology 3rd edition, New York: Pluto Press

Monaghan, J. and Just, P. (2000) Social and Cultural Anthropology: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Peoples, J. and Bailey, G. (2000) Humanity: An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 5th ed., Belmont: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning

The digital divide through an anthropological and management lens no comments

With a background in international relations, I came to Web Science with an initial interest in communication and communication technologies, and how those impact on post-conflict reconstruction and development efforts. At the time I came to identify this interest I was working for a Social Brand consultancy, helping organisations to recognise the transformational effect of social media on businesses and how to adapt to it. My first project there was to develop a ranking of Social Brands, the Social Brands 100. So while everyone around me seemed to be raving about the power of the Web and social media, I started thinking of those who don’t have access to it.

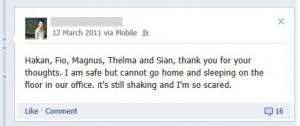

On 11 March 2011, coincidentally the launch day of the Social Brands 100, an earthquake struck Japan with devastating consequences. During the earthquake and in its aftermath, my Japanese friend was stuck in her office building for a few days, regularly posting Facebook updates to reassure friends and family that she was alright.

On 11 March 2011, coincidentally the launch day of the Social Brands 100, an earthquake struck Japan with devastating consequences. During the earthquake and in its aftermath, my Japanese friend was stuck in her office building for a few days, regularly posting Facebook updates to reassure friends and family that she was alright.

The possibilities for using social media in times of crisis seemed great. There were already forays into the idea with platforms like Ushahidi which enables crowdsourcing of information during crises via various channels (another 2011 Social Brands 100 nominee!)… But all this got me thinking that those whom such platforms or ideas could help the most were often those without access to the Internet of the Web.

Now the purpose of this assignment is to focus on particular disciplines and the approach each would take to evaluate the issue rather than on the issue itself, but we still need to define what we will look at through the disciplinary lenses. I have chosen to examine the disciplines of management and anthropology, and over the course of the next few weeks will attempt to get an idea of their epistemologies and ontologies, the basic theories that underpin them and see whether it is helpful or beneficial to combine them to understand some of the issues around the digital divide. For Chen and Wellman (2004, p. 40) ‘the digital divide involves the gap between individuals (and societies) that have the resources to participate in the information era and those that do not’. It is a complex problem characterised by wide ranging aspects – socioeconomic, technological, linguistic factors, social status, gender, life stage and geography (Chen and Wellman 2004, pp. 39-42). Going into too much detail at this stage is not necessary, as the relevant issues to be examined will be framed through each discipline, but it provides a useful starting point.

So next week I will start with Thomas Hylland Eriksen’s Small Places, Large Issues: An Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology (3rd Edition) Pluto Press, for Anthropology and for management, David Boddy’s (2008) Management: An Introduction, 4th ed., Prentice Hall.

Reference

Chen, W. and Wellman, B. (2004) ‘The Global Digital Divide – Within and Between countries’ in IT & Society Vol.1(7), pp. 39-42.

E-business (concluding thoughts – part 2 of 2) no comments

Finishing off my posts on this blog, I conclude with some final thoughts about e-business / e-commerce and the associated challenges faced by businesses in managing innovation and change in the context of the impact of Web/Internet on business competition. These bring together various topic strands from previous weeks.

For completeness sake:

• E-business refers to the integration, through the Web/Internet, of all an organization’s processes from its suppliers through to its customers. For example, a company may use a website to manage information about sales, capacity, inventory, payment and so on – and to exchange that information with their suppliers or business customers. In other words, they use the internet to connect all the links in their supply chain, so creating an integrated process (what is termed “Management in Practice’).

• E-commerce refers to the activity of selling goods or services over the Web.

As discussed last week, networked information systems enable companies to coordinate joint processes with other organizations across great distances. Transactions such as payments and orders can be exchanged electronically, thereby reducing the cost of obtaining products and services. Many such systems use Web/Internet technology, with labels such as extra-organizational systems, e-commerce, e-business systems and supply chain management systems (collectively, inter-organizational systems).

The relationship between a company and its channel partners can be fundamentally shifted by the Web/Internet (or by other applications of inter-organizational systems). They can create new relationships between an organization, its customers, suppliers and business partners, redefining organizational boundaries. Firms are using these systems to work jointly with suppliers and other business partners on product design and development and to schedule work in manufacturing, procurement and distribution.

This fact is because electronic networks can help to bypass channel partners – so-called disintermediation. Disintermediation is when intermediaries, such as distributors or brokers (whose function is to link a company to its customers), are removed. For example, a manufacturer and a wholesaler can bypass other partners and reach customers directly. The benefits of disintermediation are that transaction costs are reduced and that it enables direct contact with customers. This also makes it possible to increase the reach of companies, e.g. from a local presence to a national or international presence.

Disintermediation can be contrasted with reintermediation (the creation of new intermediaries between customers and suppliers by providing (new) services such as supplier search and product evaluation helping customers to compare offers and link them to suppliers: examples are Yahoo and Amazon).

From a management perspective, the challenge of transforming a company into an e-business lies in reorganizing all the internal processes. A major concern of companies moving towards e-commerce or e-business has been to ensure they can handle the associated physical processes. These include handling orders, arranging shipment, receiving payment and dealing with after-sales service. This gives an advantage to traditional retailers who can support their website with existing fulfilment processes. Given the negative effects of failure once processes are supported by inter-organizational systems, it seems advisable to delay connecting existing systems to the new system until robust and repeatable processes are in place.

Kanter (2001) found that the move to e-business for established companies involves a deep change. She found that top management absence, short-sightedness of marketing people and other internal barriers are common obstacles. Based on interviews with more than 80 companies on their move to e-business, her research provides ‘deadly mistakes’ as well as some lessons, including:

• Create experiments and act simply and quickly to convert the sceptics.

• Create dedicated teams, and give them autonomy. Sponsor them from the wider organization.

• Recognize that e-business requires systemic changes in many ways of working.

Earlier, I identified the management job as being to add value through the tasks of planning, organizing, leading and controlling the use of resources. In particular:

• Planning – this deals with the overall direction of the business, and includes forecasting trends, assessing resources and developing objectives. I also introduced Porter’s five forces, widely used as a tool for identifying the competitive forces affecting a business. Information technology can become a source of competitive advantage if a company can use them to strengthen one or more of these forces. Managers also use IS to support their chosen strategy – such as a differentiation or cost leadership. IS can support a cost leadership strategy when companies substitute robotics for labour, use stock control systems to reduce inventory, use online order entry to cut processing costs, or use systems to identify faults that are about to occur to reduce downtime and scrap. A differentiation strategy tries to create uniqueness in the eyes of the customer. Managers can support this by, for example, using the flexibility of computer-aided manufacturing and inventory control systems to meet customers’ unique requirements economically.

• Organization – This is the activity of moving abstract plans closer to reality, by deciding how to allocate time and effort. It is about creating a structure to divide and coordinate work. Information systems enable changes in structure – perhaps centralizing some functions and decentralizing others. For example, Siemens have used the Internet to bring more central control.

• Leading – This is the activity of generating effort and commitment towards meeting objectives. It includes influencing and motivating other people to work in support of the plans. Computer-based IS can have significant effects on work motivation, by changing the tasks and the skills required. >>>

• Controlling – Computer-based monitoring systems can constantly check the performance of an operation, whether the factor being monitored is financial, quality, departmental output or personal performance. Being attentive to changes or trends gives the business an advantage as it can act promptly to change a plan to suit new conditions.

The Web, like other new technologies, also enable processes of international business, since firms can disperse their operations round the globe, and manage them economically from a distance. The technology enables managers to keep in close touch with dispersed operations – though at the same time raising the dilemma between central control and local autonomy. This internationalisation effect also makes possible working interdependently with other organizations: previously this was constrained by physical distances and the limited amount of information that was available about the relationship. As technology has advanced, interdependent operations become more cost effective – most obviously through outsourcing and other forms of joint ventures. Companies can routinely exchange vast amounts of information with suppliers, customers, regulators and many other elements of the value chain. This implies that managers need to develop their skills of managing these links (to foster coordination and trust between network members).

In summary, the Web enables radical changes in organizations and their management. It enables management to erode the boundaries between companies, through the use of inter-organizational systems. They can then develop systems for e-commerce and e-business, ultimately connected with all stages in their supply chain.

As well as transforming the internal context of organizations, the Web also affects the external context (hand in hand with internationalization and other factors) to transform the competitive landscape in which firms operate. The Web has enabled companies offering high-value/low-weight products to open new distribution channels and invade previously protected markets. These forces have collectively meant a shift of economic power from producers to consumers, many of whom now enjoy greater quality, choice and value. Managers wishing to retain customers need continually to seek new ways of adding value to resources if they are to retain their market position. Unless they do so, they will experience a widening performance gap (when people believe that the actual performance of a unit or business is out of line with the level they desire).

I have also considered how people introduce change to alter the context, with management attempting to change elements of its context to encourage behaviours that close the performance gap. For example, when supermarkets introduced on-line shopping, their management needed to change technology, structure, people and business processes to enable staff to deliver the new service. Thus there is an interaction between context and change: with change affecting context but also context (organisational culture) affecting change.

E-business (concluding thoughts – part 1 of 2) no comments

Picking up from where I left off last week – I want to shift the focus firmly onto the impact of the Web/Internet on business competition as I move on from broad principles of management/economics to specifics. The examples used below are taken from Boddy’s ‘Management, An Introduction’.

I kick off with a consideration of Google as an illustration of the impact that the Web/Internet has had on competition between businesses. Google exemplifies a company created to use the Web/Internet – it is a pure e-business company built entirely around information technology. Since the search engine serve is free, it generates revenues by providing advertisers with the opportunity to deliver online advertising that is relevant to search results on a page. The advertisements are displayed as sponsored links, with the message appearing alongside search results for appropriate keywords. They are priced on a cost-per-impression basis, whereby advertisers pay a fixed amount each time their ad is viewed. The charge depends on what the advertiser has bid for the keywords, and the more they bid the nearer the top of the page their advertisement will be. Google has rapidly expanded the range of services it offers.

Pure e-businesses such as Google which focuses on search processes (other examples include easyGroup which exclusively sells its services online and eBay which facilitates online transactions) can be contrasted with companies existing before the Web/Internet but which use it to support many of their activities. They may still perform the same functions, but the Web/Internet often enables them to offer new services through an additional distribution channel online (such as banks).

As well as offering new ways of doing business, the Web/Internet also affects the way services are created and delivered. Examples include: delivering media content; satellite freight tracking services; and, social networking sites. Picking up on this last example in particular, social networking sites (types of community systems) enabling people to exchange information have grown very quickly. Setting up blogs is one major use, as are websites through which people with particular interests exchange information. They are significant for businesses even if they extend beyond the firm, since customers can use them to exchange positive or negative information about the company. These applications affect the strategy and competiveness of organization.

The publishing industry (compare music, film and journalism) is an example of a business model founded on information (its gathering, processing and dissemination) for whom the Web is the biggest threat. As digitisation and the Web have reduced the cost of the dissemination of information, it undermines the value proposition of those industries built on its premise.

There is also an internal business impact of the Web in terms of changing various aspects of organisational activity. Common information systems based on the Web/Internet move information between organizations, often having direct links with customers. This is part of a broader assessment of how information technology, in general, is affecting the way that business is carried out.

One way to consider the impact of the Web/Internet on business is by geographic reach. Inter-organisational information systems link organisations electronically by using networks that transcend company boundaries. They enable firms to incorporate buyers, suppliers and partners in the redesign of their key business processes, thereby enhancing productivity, quality, speed and flexibility. New distribution channels can be created and new information-based products and services can be delivered. In addition, many information systems radically alter the balance of power in buyer-supplier relationships, raise barriers to entry and exit and, in many instances, shift the competitive position of industry participants.

From an alternative perspective as an information system, the Web/Internet has had wide effects on managing data, information and knowledge. It can, for example, be used to integrate processes, from suppliers through to customer delivery. Managers must ensure that their organisation makes profitable use of the possibilities that the Web/Internet offers in a way that suits their particular business; and, not just as a technology challenge, but also as a ‘people challenge’. For example, network systems help people to communicate and interact with each other, but they do not define how they should do so (such as who should gain access to which part of the system or who is responsible for responding to customer comments on a blog – these are matters to be implemented and modified in the light of experience).

A useful distinction can be made between intranets and extranets. The former is a private computer network operating within an organisation, using Web/Internet standards and protocols and security protected. An extranet is a closed, collaborative network that uses the Web/Internet to link businesses with specified suppliers, customers or other trading partners. It can be linked to business intranets where information is accessible through a password system.

The simplest Web/Internet applications provide information, enabling customers to view products or other information on a company website; conversely, suppliers use their website to show customers what they can offer. Web/Internet marketplaces are developing in which groups of suppliers in the same industry operate a collective website, making it easier for potential customers to compare terms through a single portal. The next stage is to use the Web/Internet for interaction. Customers enter information and questions about, say, offers and prices. The system then uses the customer information, such as preferred dates and times of travel, to show availability and costs.

Another use is for transactions, when customers buy goods and services through a supplier’s website. Conversely a supplier who sees a purchasing requirement from a business (perhaps expressed as a purchase order on the website) can agree electronically to meet the order. The whole transaction, from accessing information through ordering, delivery and payment, can take place electronically.

Finally, a company achieves integration when it links its own information system to customers and suppliers: it becomes an e-business. Dell Computing is an example. Other companies use the Web/Internet to create and orchestrate active customer communications (e.g. Kraft, Intel and Apple). These communications enable companies to become closer to their customers and to learn how best to improve a product/service much more quickly than is possible through conventional market research techniques.

In conclusion, the Web/Internet is radically challenging many established ways of doing business. Combined with political change, this is creating a wider, often global, market for many goods and services.

Next week, in my final post, I will round up on the topics of e-commerce and e-business and the associated challenges faced by businesses in managing innovation and change.

Business Economics Week 3 no comments

This week I start by looking at business strategy from the perspective of economics. There are basic economic principles underpinning the determination, choice and evaluation of business strategy.

As mentioned in my post on management studies from a few weeks’ back, right strategies (the ways in which organizations address their fundamental challenges over the medium to long-term) are crucial for businesses to survive and beat the competition. Strategic-minded thinking includes comprehensive consideration and reflection upon a business’ mission statement and its vision. For both economists and management theorists, therefore, the aims of a business determines its strategy. Equally relevant, however, for both disciplines are internal capabilities and industry structure/conditions.

Like management theory, economists adopt Porter’s five forces model of competition (Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, 1980) which set out to identify those factors which are likely to affect an organization’s competitiveness. These five forces are:

• The bargaining power of suppliers

• The bargaining power of buyers

• The threat of potential new entrants

• The threat of substitutes

• The extent of competitive rivalry

I will be returning to these five forces next week in the context of considering, specifically, how they apply to the effects of the Web. In the meantime, it is worth pointing out that the five forces model does have limitations. For example, it is a largely static model whereas conditions change over time requiring strategy to evolve over time. Notably, also, Porter’s model suggests that success is dependent on competition rather than the potential for collaboration and cooperation (such as with those downstream vertically from a supplier).

Value chain analysis is also closely linked to the five forces model (according to the definition of Sloman, Hinde and Garratt, value chain “shows how value is added to a product as it moves through each stage of production from the raw material stage to its purchase by the final consumer”). Analysis of the value chain involves evaluating how each of the various operations within and around an organization contributes to the competitive position of the business). Ultimately it is these value-creating activities, which can be primary or support activities, that shape a firm’s strategic capabilities.

Turning to growth strategy, it is worth making a nod here to vertical integration (this will become more relevant when considering the effects of the Web in facilitating disintermediation of value chains over the next two weeks). There are a variety of reasons why forward or backward vertical integration might lead to cost savings (such as through economies of scope and scale), including: production economies; coordination economies; managerial economies; and financial economies. The major problem with vertical integration as a form of expansion is that the security it gives the business may reduce its ability to respond to changing market demands.

Other points of comparison and dissimilarity between management and economics can start to be drawn. For example, a point of difference is economics’ focus on theories related to short-term/long-term profit maximization. There is much debate among economists about whether profit-maximizing theories of the firm are unrealistic (largely due to a lack of information or lack of motivation). This focus is where costs concepts and graphs (demand curves in particular) come in.

A more practical illustration given by Sloman, Hinde and Garratt in respect of the search for profits is the video games war where there are high costs, but also high rewards, from a long-term perspective. In considering the secret of success in the market, online gaming capability and global connectivity are significant factors. Moreover, connection to the internet has facilitated a move towards the use of consoles as ‘digital entertainment centres’, in which users can download content. These developments are likely to continue as long as broadband internet connectivity improves and remains fairly cheap to use.

Finally, in economics, there are various theories of strategic choice (such as cost leadership, differentiation and focus strategy). These strategies can be combined. For example, Amazon had a clear niche market focus strategy – to sell books at knockdown prices to online customers – and this has become a mass market with the spread of the Web and due to lower costs.

Next week, I want to move the focus firmly onto the impact of the Web on business competition as I move on from broad principles of management/economics to specifics. I will kick off with a consideration of Google’s business model.

Introducing Business Economics no comments

This week I turn to my second discipline, economics, as a basis for considering a different slant on my research question (how the Web changes competition between businesses). While having some degree of economics knowledge in my background, I have approached the subject area afresh in a systematic fashion with guidance from a book looking at economics for businesses (Sloman, Hinde and Garratt 2010).

My starting position is to look at the essence of economics: how to get the best outcome from limited resources. In other words, economics tackles the problem of scarcity which is a central problem faced by all individuals and societies. Demand and supply and the relationship between them are central to this analysis. Also key is the concept of choice (known as “opportunity cost”): the sacrifice of alternatives in the production or consumption of products or services.

Economics is traditionally divided into two main branches: macroeconomics and microeconomics. Macroeconomics examines the economy as a whole at a national or indeed international level (i.e. aggregate demand and supply), whereas microeconomics examines the individual parts of the economy. The latter includes all the economic factors that are specific to a particular firm operating in its own particular market. As microeconomics explores issues surrounding competition between firms, and due to limits in time, I will not be looking at macroeconomics in any detail (other than indirectly via a general awareness of the factors that affect economies as a whole, which in turn affect individual firms as an important determinant of their profitability).

From a microeconomics perspective, the choices made by firms are studied alongside their results. Such choices include how much to produce, what price to charge, how many inputs to use, what types of inputs to use and in what combinations, how much to invest etc. Making such choices involve rationality in weighing up the marginal benefits versus the marginal costs of each activity to best meet the objectives of the firm.

It is worth pausing at that point to make a comparison between the relevance of economics to business decision-making and the contents of my previous blog posts on management study’s approach to business activities and competition between firms. Both use similar terminology and look to the structure of industry and its importance in determining firms’ behavior. They also both look at ranges of factors that affect business decisions and consider the wider environment in which firms operate (including conditions of competition in relevant markets) in helping to devise appropriate business strategies. For example, Sloman, Hinde and Garratt also refer to how the pace of technological change has had a huge impact on how firms produce products and organize their businesses, together with a ‘PEST’ – political, economic, social and technological – analysis (compare my previous blog entry ‘Management 102’).

Where economics (more specifically, we can call it ‘business economics’) differs from management is its focus on how firms can respond to demand and supply issues. In other words, its emphasis is more on internal decisions of firms related to achieving rationally efficient outcomes and the effects of such decision-making on a firm’s rivals, its customers and the wider public.

In keeping with the theme of efficiency, economics has traditionally considered that business performance should be measured against a structure-conduct-performance (structure affecting conduct affecting performance) paradigm measured by several different indicators. Performance is also determined by a wide range of internal factors and external factors other than just market structure, such as business organization, the aims of owners and managers.

In returning to the theme of how economics differs from management/business studies, economists have traditionally paid little attention to the ways in which firms operate and to the different roles they might take. Firms were often seen merely as organizations for producing output and employing inputs in response to market forces. In other words, virtually no attention was paid to how firm organization and how different forms of organization would influence their behavior. This position has changed as economist interest in firms’ roles with respect to resource allocation and production (and how their internal organization affects their decisions) has increased.

Economists have also conventionally assumed that firms will want to maximize profits. The traditional theory of the firm shows how much output firms should produce and at what price, in order to make as much profit as possible. While it may be reasonable to assume that the owners of firms will want to maximize profits, it is the management (as separate from the shareholders) that normally takes decisions about how much to produce and at what price. Management may be assumed to maximize their own interests, which may conflict with profit maximization by the firm. In summary, the divorce of ownership from control implies that the objectives of owners and managers may diverge and hence the goals of firms may be diverse.

In their introductory section on business and economics, Sloman, Hinde and Garratt include an interesting case study on the changing nature of business in those countries where economies are knowledge driven and innovation is therefore central to business success. They include a quote from a European Commission publication (Innovation Management and the Knowledge-Driven Economy, 2004) on this point:

“With this growth in importance, organisations large and small have begun to re-evaluate their products, their services, even their corporate culture in the attempt to maintain their competitiveness in the global markets of today. The more forward-thinking companies have recognised that only through such root and branch reform can they hope to survive in the face of increasing competition.”

Thus, it is suggested that the dynamics of knowledge economies require a fundamental change in the nature of business. This is an interesting comment in considering the impact of the Web on competition from an economical viewpoint. Knowledge is fundamental to economic success in many industries. The result is a market in knowledge, with knowledge diffusing and cutting across industry boundaries. Another result is the increasing outsourcing of various stages of production and collaborations across industries. Furthermore, whereas in the past businesses controlled information, today access to information via sources such as the Web means that power is shifting towards consumers.

Next week I will turn to the concept of markets from an economic viewpoint and how competition is assessed via the theory of the market.

Introduction to Management 103 no comments

Last week I wrote about organization contexts. This week I wanted to change tack to consider business planning and marketing, and how they fit within the competitive process (in particular, in the online world). Changes in the external world create uncertainty and management planning is a systematic way to cope with that and to adapt to new conditions.

Strategic plans apply to the whole organization or business unit, setting out the long-term goals and objectives of an enterprise (effectively, where it wants to be and how to get there). It will usually combine an analysis of external environmental factors with an internal analysis of the organization’s strengths and weaknesses. This can be referred to as a SWOT assessment (bringing together reflection on internal Strengths and Weaknesses and external Opportunities and Threats). It includes drawing information as described in last week’s post as Porter’s five forces analysis of the competitive environment in which organizations are situated.

Forecasting is relevant in dynamic and complex situations but encounters problems when the sector is marked by rapidly changing trends. So-called scenario planning is an attempt to create coherent and credible alternative stories about the future. For example, consideration might be given to how the internet (as a major force in the external environment) might affect a company’s business over the next 5-10 years. According to Boddy, this process can bring together new ideas about the environment into the heads of managers, thus enabling them to recognize new and previously unthinkable possibilities. This, in turn, facilitates the development of contingency plans to cope with outcomes that depart from the most likely scenario. On the downside, the scenario planning process is time-consuming and costly.

Once a plan has been formulated, the next stage is to identify what needs to be done by whom. New technological projects often fail, for example, because planners pay too much attention to the technological aspects and too little to the human aspects of structure, culture and people. Good communication and implementation structure are therefore key.

Hand-in-hand with planning is the topic of decision-making under management theory, including the ability to recognize a problem and set objectives in trying to find a solution. A company facing rapidly changing technological and business conditions needs to be able to make decisions quickly. Boddy gives the example of managers at Microsoft being slow to realize that Linux software was a serious threat which caused a delay in competitive reaction.

There are various decision-making management models, including: computational strategy (rational model); compromise strategy (political model); judgmental strategy (incremental model); and, inspirational strategy (garbage can model). It is interesting to make comparisons between economics and the first aforementioned model which suggests that the manager’s role is to maximize economic return to the company by making decisions based on economically rational criteria. Developments in technology have encouraged some observers, says Boddy, to anticipate that computers would be able to take over certain types of decisions from managers. It is true that new applications are used in many organizational settings when decisions depend on the rapid analysis of large quantities of data with complex relationships by using rational, quantitative methods (such as in utility companies). Such automated decision-making systems “sense online data or conditions, apply codified knowledge or logic and make decisions – all with minimum amounts of human intervention” (Davenport and Harris, 2005). Of course, a behavioral theory of management decision-making – as well as economics in general – is also possible.

Understanding strategic management decisions also helps to analyze an organization’s perceived relationship with the outside world set against the particular features of the market in which it competes. In the early stages of a market’s growth, there are often few barriers to entry and establishing customer loyalty is all-important, but this changes as the market matures and customers become familiar with the products being sold. Markets also vary in their rate of technological change. At one extreme, firms experience a slow accumulation of minor changes, while at the other they face a constant stream of radical new technologies that change the basis of competition. Managers need to identify the core competences that an organization has or needs to compete effectively. Analysis of the separate activities in the value chain can assist in this respect: the firm’s cost position and its basis of differentiation from its competitors to add value being two main sources of competitive advantage.

It is a moot question to what extent strategy perspectives developed when the competitive landscape contained only offline firms are still relevant in the internet age. The Web allows firms to overcome barriers of time and distance, to serve large audiences more efficiently while also targeting groups with specific needs, and to reduce many operating costs. However, it has been argued (Kim 2004) that some things stay the same – such as the need to invest in a clear and viable strategy. On that basis, generic strategies of differentiation and cost leadership still apply to online business. Nonetheless, a focus strategy (involving targeting a narrow market segment, either by consumer group or geography) is not as relevant to online firms as it is to offline ones because the Web enables companies to reach both large and tightly defined companies very cheaply. Indeed, Kim (2004) argues that online strategies may be proposed as forming a continuum of cost leadership and differentiation as an integrated competitive strategy rather than as alternatives as they are sometimes conceived (think of how Ryanair and British Airways now compete in closer proximity to one another due to the online effect).

Marketing has been defined as a social and managerial process by which individuals and groups obtain what they want through creating and exchanging products and value with each other (Kotler and Keller 2006). Its basic function is to attract and retain customers at a profit.

In order to identify customers, and select the marketing mix that will satisfy customer demands and succeed in achieving organizational objectives, managers need information about consumer demands, competitor strategies and changes in the marketing environment. Marketing is, therefore, an information-intensive activity involving understanding buyer behavior. Aware of a need, consumers also search for information that will help them decide which product to buy.

A marketing channel decision for companies is whether to make purchases of their products available online. This channel allows easy gathering of data for marketing purposes. This decision has been embraced by many businesses such as easyjet and lastminute.com. Using electronic channels of distribution is a differentiation tool, on the grounds that consumers prefer online convenience and see this as a product feature. Indeed, for many companies, online product distribution is a complementary channel used to widen product access to geographically remote markets (e.g. supermarkets, which often offer discounts over store prices).

This point ties in more generally to issues around how existing physical businesses can take advantage of the opportunities that the Web offers. For example, Virgin managers were quick to pick up on the fact that their businesses were ideally suited to e-commerce in the early internet years. To exploit this potential, they decided to streamline their online services with a single Virgin web address. This general topic is one to which I would like to return (in particular, I have taken out a book from the library by Groucutt and Griseri entitled ‘Mastering e-business’ which I would like to work through).

However, in the interests of balance, next week I turn to my other discipline and field of interest: economics 101.

Introduction to Management 102 no comments

I pick up from where I left off last week – in particular, consideration of the field of management studies from the perspective of an organization (to be managed) as an ‘open system’. This conceptualization implies that various sub-systems should be considered from a management engagement viewpoint: the internal (towards maintenance of the system) and external (towards the competitive position of the system). One of the challenges under management theory is how to balance these competing values upon management time: in particular, how to trade-off the encouragement of flexibility and change, while still retaining control to ensure employees act appropriately.

In returning to the main research focus – how the Web/Internet is changing the nature of competition between businesses – an open system emphasizes how objectives, plans and solutions must adjust rapidly to changes in the external environment. These changes can come from a variety of sources. Boddy gives examples of the increasingly global nature of the economic system at large, deregulation in certain industries, the closer integration between many different areas of business (such as telecoms and entertainment), increasing consumer expectations and computer-based information systems. Many modern-day organizations operate in non-linear systems in which small changes are amplified through many interactions with other variables so that the eventual effect is unpredictable. In other words, management decisions should be grounded in the external context in which the organization is situated and the long-term consequences of a management decision can be majorly disrupted by circumstances in the outside world in an unforeseen manner.

Boddy goes on to introduce the idea of the competitive environment (defined as “the industry-specific environment comprising the organization’s customers, suppliers and competitors” or “micro-environment”). He distinguishes it from the “general environment (defined as the “political, economical, social, technological, (natural) environment and legal factors that affect all organizations” or “macro-environment”), as illustrated below:

Together, they make up the “external environment” or “external context”. Forces in the external environment become part of an organization’s agenda when internal or external stakeholders pay attention to them and act to place them on the management agenda. In turn, these demand a response (see next week for more on management theory related to the type of response).

In terms of analyzing the competitive environment, Porter put forward a theory of five forces which most directly affect management and the ability to earn an acceptable return. These are also found in economic theory and competition law: the ability of new competitors to enter the industry, the threat of substitutable products, the bargaining power of buyers, the bargaining power of suppliers and the rivalry amongst existing competitors. This analysis can also be applied at an industry level to determine overall profitability, being factors which influence prices, costs and investment requirements, as illustrated below:

To give one example, technological change can affect the proximity of competition between products which in turn can constrain a firm’s ability to raise price (Boddy gives the example of YouTube threatening established media companies and online recruitment threatening the revenues that newspapers receive from job advertisements).

Where management differs from economics is the nature of the response. Through analyzing the forces in the competitive environment, managers aim to seize opportunities, counter threats and generally improve their position relative to their firm’s competitors in the future. Like economics, however, management also looks at trends, such as the state of the economy which is a major influence on consumer spending and capital investment plans. Sociological trends can also be relevant. For example, many consumer businesses are changing direction from a strategy aimed at mass market towards developing much small brands directed at small, distinctive groups of consumers. This reflects the growing diversity of the population, with many personal and individual preferences more apparent (such as through the Web). Again, in turn, this shift has severe implications for media that relied on advertising from mass market advertising. There are also many examples of digital technologies affecting established markets (such as DVDs, MP3s, broadband services offering delivering online content, VoIP and digital photography).

In summary, critical reflection on business environment conditions is essential to the type of management strategy adopted. Next week I turn to theories of generic management activities of planning and decision-making, including strategy and marketing (to lead into discussions of how e-marketing has revolutionized the business world).

Introduction to Management 101 no comments

I have been reading David Boddy’s ‘Management an introduction’ (4th edition). It’s a useful introduction to the different ways in which management has emerged as a social science, including the main theoretical perspectives on management.

Interestingly, the first case study is Ryanair and how its managers were quick to spot the potential of the Web by opening www.ryanair.com as a booking site in 2000. Within a year it was selling 75% of seats online, and now sells almost all seats this way.

In considering what ‘management’ is, an important component is innovation. Computers and network (the new agents of communication) has propelled management into the new economy through innovation. To give one simple example from Boddy, the use of emails has sped up communication enabling managers to strengthen their interpersonal roles.

Thus, it seems to me that technology (including the Web) is both an external and internal force upon management: it facilitates innovation to beat the external competition; while also providing an opportunity for corporate entities to streamline themselves internally via more efficient working practices. In the nature of a double-edged sword, however, it may also be the undoing of those businesses that do not use them efficiently.

As Boddy points out, everywhere the Web is enabling great changes in how people organise economic activity, equivalent to the Industrial Revolution in the 19/20th century. This includes the challenges of coping with the transition to a world in which ever more business is done on a global scale. Those managing a globally competitive business requires flexibility, quality and low-cost production. Thus managers want production processes that help them to organise as efficiently as possible from a technical perspective.

In terms of different models of management, at a basic level we can think of management as the way in which enterprises add value to inputs. Building on this, several perspectives can be taken with no single model offering a complete solution. Models reflect their context in terms of the most pressing issues facing managers at the time. To give one example, sometimes manufacturing efficiency is necessary but not sufficient. Drucker (1954) observed that customers do not buy products, but the satisfaction of needs: what they value may be different from what producers think they are selling. Managers, Drucker argued, should develop a marketing mindset, focused on what customers want, and how much they will pay. As a consequence of business becoming more global (again partly as a consequence of the Web) managers need to react quickly to international trends of changing customer needs and how to scale up to take advantage of global opportunities.

Boddy also discusses the concept of the corporate organization from a management perspective. Just as the Web is compared to the neural functions of brains, organisms, culture, machine, so is a business.

I was also struck by the interdependent links drawn between management and technology (as mentioned above) as compared with our discussions with Cathy in relation to science and technology. For example, operational research teams set up to pool the expertise of scientific disciplines are now used to help run complex civil organisations.

But, like with the Web, technology is only part of the solution. A key plank of management is human relations. Management solutions lie in reconciling technology and social needs (i.e. appreciating that work systems are socio-technical in nature). So whereas I had previously been concentrating on the Web in its influence on external business strategies, this can only be appreciated by considering how it has also revolutionized internal operations, in addition to the links between the two and the outside world which provides inputs (what Boddy calls the ‘open models’ system conception of an organisation).

In a nutshell, I have learnt that management is about relationships between subsystems and whole systems. To what extent, I wonder, is the Web breaking down the boundaries between these and blurring the conceptualization of an internal world / external world hard-line divide in business (i.e. now that consumers can become producers of certain products/services and more flexible and freelance working practices are becoming the norm)?