E-business (concluding thoughts – part 1 of 2) no comments

Picking up from where I left off last week – I want to shift the focus firmly onto the impact of the Web/Internet on business competition as I move on from broad principles of management/economics to specifics. The examples used below are taken from Boddy’s ‘Management, An Introduction’.

I kick off with a consideration of Google as an illustration of the impact that the Web/Internet has had on competition between businesses. Google exemplifies a company created to use the Web/Internet – it is a pure e-business company built entirely around information technology. Since the search engine serve is free, it generates revenues by providing advertisers with the opportunity to deliver online advertising that is relevant to search results on a page. The advertisements are displayed as sponsored links, with the message appearing alongside search results for appropriate keywords. They are priced on a cost-per-impression basis, whereby advertisers pay a fixed amount each time their ad is viewed. The charge depends on what the advertiser has bid for the keywords, and the more they bid the nearer the top of the page their advertisement will be. Google has rapidly expanded the range of services it offers.

Pure e-businesses such as Google which focuses on search processes (other examples include easyGroup which exclusively sells its services online and eBay which facilitates online transactions) can be contrasted with companies existing before the Web/Internet but which use it to support many of their activities. They may still perform the same functions, but the Web/Internet often enables them to offer new services through an additional distribution channel online (such as banks).

As well as offering new ways of doing business, the Web/Internet also affects the way services are created and delivered. Examples include: delivering media content; satellite freight tracking services; and, social networking sites. Picking up on this last example in particular, social networking sites (types of community systems) enabling people to exchange information have grown very quickly. Setting up blogs is one major use, as are websites through which people with particular interests exchange information. They are significant for businesses even if they extend beyond the firm, since customers can use them to exchange positive or negative information about the company. These applications affect the strategy and competiveness of organization.

The publishing industry (compare music, film and journalism) is an example of a business model founded on information (its gathering, processing and dissemination) for whom the Web is the biggest threat. As digitisation and the Web have reduced the cost of the dissemination of information, it undermines the value proposition of those industries built on its premise.

There is also an internal business impact of the Web in terms of changing various aspects of organisational activity. Common information systems based on the Web/Internet move information between organizations, often having direct links with customers. This is part of a broader assessment of how information technology, in general, is affecting the way that business is carried out.

One way to consider the impact of the Web/Internet on business is by geographic reach. Inter-organisational information systems link organisations electronically by using networks that transcend company boundaries. They enable firms to incorporate buyers, suppliers and partners in the redesign of their key business processes, thereby enhancing productivity, quality, speed and flexibility. New distribution channels can be created and new information-based products and services can be delivered. In addition, many information systems radically alter the balance of power in buyer-supplier relationships, raise barriers to entry and exit and, in many instances, shift the competitive position of industry participants.

From an alternative perspective as an information system, the Web/Internet has had wide effects on managing data, information and knowledge. It can, for example, be used to integrate processes, from suppliers through to customer delivery. Managers must ensure that their organisation makes profitable use of the possibilities that the Web/Internet offers in a way that suits their particular business; and, not just as a technology challenge, but also as a ‘people challenge’. For example, network systems help people to communicate and interact with each other, but they do not define how they should do so (such as who should gain access to which part of the system or who is responsible for responding to customer comments on a blog – these are matters to be implemented and modified in the light of experience).

A useful distinction can be made between intranets and extranets. The former is a private computer network operating within an organisation, using Web/Internet standards and protocols and security protected. An extranet is a closed, collaborative network that uses the Web/Internet to link businesses with specified suppliers, customers or other trading partners. It can be linked to business intranets where information is accessible through a password system.

The simplest Web/Internet applications provide information, enabling customers to view products or other information on a company website; conversely, suppliers use their website to show customers what they can offer. Web/Internet marketplaces are developing in which groups of suppliers in the same industry operate a collective website, making it easier for potential customers to compare terms through a single portal. The next stage is to use the Web/Internet for interaction. Customers enter information and questions about, say, offers and prices. The system then uses the customer information, such as preferred dates and times of travel, to show availability and costs.

Another use is for transactions, when customers buy goods and services through a supplier’s website. Conversely a supplier who sees a purchasing requirement from a business (perhaps expressed as a purchase order on the website) can agree electronically to meet the order. The whole transaction, from accessing information through ordering, delivery and payment, can take place electronically.

Finally, a company achieves integration when it links its own information system to customers and suppliers: it becomes an e-business. Dell Computing is an example. Other companies use the Web/Internet to create and orchestrate active customer communications (e.g. Kraft, Intel and Apple). These communications enable companies to become closer to their customers and to learn how best to improve a product/service much more quickly than is possible through conventional market research techniques.

In conclusion, the Web/Internet is radically challenging many established ways of doing business. Combined with political change, this is creating a wider, often global, market for many goods and services.

Next week, in my final post, I will round up on the topics of e-commerce and e-business and the associated challenges faced by businesses in managing innovation and change.

Cognitive psychology, artificial intelligence, and social cognition in e-learning no comments

The following is a brief discussion of random ideas I have so far. My blogs in the next few weeks will elaborate on some of the following ideas. These ideas in their present form are by no means fully formed or coherent. Rather, there are posted here as a general guide for me to investigate further with a general sense of direction eventually leading to material suitable for our assignment.

Cognitive psychology/artificial intelligence along with constructivism in learning. Is it possible to compare constructivism with the concept of a filing system in a computer? For example where we talk about scaffolding in education, is it is similar idea to rural and a filing system in a computer? In a computer, there is a short-term memory as well as a long-term memory. RAM and ROM, and that’s what it’s all about.

Social cognition dealt with a lot on the behaviour of an individual in a social setting. It dealt with how the individual looks at oneself, how they perceive the characteristics of a group, and how they behave accordingly. Could it be that is part of this awareness is what drives the popular uptake of social networking? If this were so, how much of that can be gleaned and adopted for collaborative learning via the Internet?

Summary of social cognition no comments

Over the last few weeks, I have learned much about social cognitive, social identity, social representations, and discursive perspectives. In particular, I have looked further into social perception, attitudes, self and identity. I have found it very interesting to see how within the same topics, different models coexist to describe the same thing. In my previous posts, I have also tried to highlight the common ground as well as the differences between these models.

As I began reading, it became clear to me that the so-called individual cannot be properly and fully understood in abstract isolation from the social. Even in the most minimal of social groups constructed in the laboratory, the group has meaning because of the network of social relationships in which participants are implicated.

I have also come to conclusion that humans do actively construct their own social environment. Exactly how this is done, people seem to differ in their own opinion. Some resting on a realist philosophy of science suggests that it is possible to build a theoretical knowledge of the world which resembles truth. They assert that some theoretical accounts can be judged to be more true than others. However the discursive perspective does not accept that view, and differences between different theoretical accounts arbitrated, by recourse was to empirical data. Rather, one account prevails over another because of the attitude of the social and political processes of negotiating shared understandings of the world, not because of its greater truth value.

I cannot decide between the two viewpoints. However, what is clear to me is that social psychology cannot proceed without all thorough and more adequate analysis of the truth and reality. The bottom line from me is, it may well be the case that one theoretical or empirical account of the social issue prevails because of the social and political processes of negotiating shared understanding rather than because of the ability of data, but that date are themselves are also an important part of the way in which understandings are negotiated.

Who am I? no comments

This week I have been reading around the subject of self and identity, which is concerned with how the everyday concept of self has been theorised in social psychology.

Social cognitive models describe self as a piece of knowledge and considers how particular kinds of self representation are assessed in different situations. There seems to be a lengthy discussion on the ideal and the ought self as opposed to the actual self. Discrepancies between the ideal and the actual or the ought and the actual are said to be responsible for the positive or negative effects on self-esteem. The plan is that people have for achieving this eternity of cells in the future, as well stay current discrepancies from them, are considered to be important contributors to people’s experience of themselves in the present. In addition, it is noted that people engage in processes of self-evaluation and self regulation, the assessment of how one is doing compared to others, and intentional efforts to modify aspects of one’s self. All these models have something to do with the ways in which the knowledge that people have about themselves becomes a relevant in particular circumstances, and how these guides are their behaviour accordingly.

On the other hand, social identity as a contrasting model considers how the social groups of which we are members impact on our sense of self. According to this model, all experiences in children live Kurds continuously from interpersonal to intergroup interaction. It is believed that there is the further we move towards the intergroup situation, the more depersonalise our sense of self becomes. In other words, we begin to think of ourselves more and more in terms of those characteristics that we share with other group members. This in turn is closely linked to personal attitudes and perception of group identity.

This new model has led to further research into ways that people share representations of self within the groups. In particular, they consider the ways in which socially shared representations of the self and of the social groups that contribute to one’s sense of identity shape the context within which people develop their self concepts. Of course, individuals may differ in the extent to which elements of particular social representations are incorporated into their self concepts, the importance of social representations in forming a shorter and vermin surrounding these selves means that social representations cannot be reduced to individual difference variables.

Finally, I have touched on the work of social constructionist. Some seem to believe that the conditions of contemporary life are undermining the notion of an integrated and stable self. However, others have also argued that the constructed the nature of the self is being reviewed in the ordinary experiences of everyday life, and is provoking the prices as the ontological basis of cells apparently unravels. Therefore, the challenge for people in this world is to construct a sense of identity which does not require the self to be a faithful reflection of inner capacities and qualities but which, rather, sees the self as a constructed achievement of relational social life.

Moving on

This is my last reading based post on this blog. In view of the time left, my next blog will focus on summarising and recollecting what I have learned so far, and will begin to move towards a synthesis version of all the information presented. In particular, these will be discussed or analysed in relation to E learning.

Market Segmentation no comments

In marketing a key concept is market segmentation – deciding how to divide your market into individual segments so you can target your products and services, prices, advertising etc to that segment’s needs and demands.

Marketing can be conducted a different levels of segmentation:

Mass-marketing – no segmentation. This is not necessarily a bad strategy. It spreads costs across the largest possible number of customers and makes for a consistent brand image. It does however tend to lead to competing on price which may lead to low profit margins.

Segmented markets – this would be something like the over 55s – quite broad and usually with a lot of competitors – but nevertheless defining some characteristics of the market e.g. interested in holidays during the school term, not interested in low cost mortgages or nappies!

Niche marketing – quite specific groups within a market segment such as the over 55s gay and lesbian niche (yes there are companies addressing this niche). Often an unexpected group with little or no competition.

Local marketing – marketing to a specific town or even store. A supermarket chain may authorise local managers to stock and promote products specific to their store. Can be effective but have to be wary of costs and diluting brand.

Individual marketing – this has always existed at a local level. If the village shop stocks vegemite because you are the one Australian in the village who buys it – then that is individual marketing. Famously the web has enabled large companies to do mass customisation i.e. mass individual marketing. The paradigm example being Amazon.

How does this relate to my research question? The trend in science communication with the public over recent years has been to move away from science communication – which is a mass market one way process – tell them the truth which we scientists are the authorities on – to public engagement. Learn how the public uses scientific knowledge and how local knowledge can integrate with and enhance scientific knowledge. This implies segmentation – possibly down to the individual marketing level.

Business Economics Week 3 no comments

This week I start by looking at business strategy from the perspective of economics. There are basic economic principles underpinning the determination, choice and evaluation of business strategy.

As mentioned in my post on management studies from a few weeks’ back, right strategies (the ways in which organizations address their fundamental challenges over the medium to long-term) are crucial for businesses to survive and beat the competition. Strategic-minded thinking includes comprehensive consideration and reflection upon a business’ mission statement and its vision. For both economists and management theorists, therefore, the aims of a business determines its strategy. Equally relevant, however, for both disciplines are internal capabilities and industry structure/conditions.

Like management theory, economists adopt Porter’s five forces model of competition (Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, 1980) which set out to identify those factors which are likely to affect an organization’s competitiveness. These five forces are:

• The bargaining power of suppliers

• The bargaining power of buyers

• The threat of potential new entrants

• The threat of substitutes

• The extent of competitive rivalry

I will be returning to these five forces next week in the context of considering, specifically, how they apply to the effects of the Web. In the meantime, it is worth pointing out that the five forces model does have limitations. For example, it is a largely static model whereas conditions change over time requiring strategy to evolve over time. Notably, also, Porter’s model suggests that success is dependent on competition rather than the potential for collaboration and cooperation (such as with those downstream vertically from a supplier).

Value chain analysis is also closely linked to the five forces model (according to the definition of Sloman, Hinde and Garratt, value chain “shows how value is added to a product as it moves through each stage of production from the raw material stage to its purchase by the final consumer”). Analysis of the value chain involves evaluating how each of the various operations within and around an organization contributes to the competitive position of the business). Ultimately it is these value-creating activities, which can be primary or support activities, that shape a firm’s strategic capabilities.

Turning to growth strategy, it is worth making a nod here to vertical integration (this will become more relevant when considering the effects of the Web in facilitating disintermediation of value chains over the next two weeks). There are a variety of reasons why forward or backward vertical integration might lead to cost savings (such as through economies of scope and scale), including: production economies; coordination economies; managerial economies; and financial economies. The major problem with vertical integration as a form of expansion is that the security it gives the business may reduce its ability to respond to changing market demands.

Other points of comparison and dissimilarity between management and economics can start to be drawn. For example, a point of difference is economics’ focus on theories related to short-term/long-term profit maximization. There is much debate among economists about whether profit-maximizing theories of the firm are unrealistic (largely due to a lack of information or lack of motivation). This focus is where costs concepts and graphs (demand curves in particular) come in.

A more practical illustration given by Sloman, Hinde and Garratt in respect of the search for profits is the video games war where there are high costs, but also high rewards, from a long-term perspective. In considering the secret of success in the market, online gaming capability and global connectivity are significant factors. Moreover, connection to the internet has facilitated a move towards the use of consoles as ‘digital entertainment centres’, in which users can download content. These developments are likely to continue as long as broadband internet connectivity improves and remains fairly cheap to use.

Finally, in economics, there are various theories of strategic choice (such as cost leadership, differentiation and focus strategy). These strategies can be combined. For example, Amazon had a clear niche market focus strategy – to sell books at knockdown prices to online customers – and this has become a mass market with the spread of the Web and due to lower costs.

Next week, I want to move the focus firmly onto the impact of the Web on business competition as I move on from broad principles of management/economics to specifics. I will kick off with a consideration of Google’s business model.

Economics of intellectual property no comments

In my last post I talked about how economics is necessary because of the scarcity of goods. What is interesting in looking at the economics of intellectual property is that intellectual goods aren’t scarce in the way that other goods are. So does that mean we don’t actually need economics when it comes to intellectual goods?

In short, the answer is no. Even though intellectual goods aren’t scarce like land or labour, they are made artificially scarce through government policy. This creates a market for them.

To see why intellectual goods aren’t scarce, consider this quote from Benjamin Franklin (17??)

“If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of everyone, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it.

Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.

That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation. Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.”

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Isaac McPherson, 13 August 1813

http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/a1_8_8s12.html

An important difference between intellectual property and non-intellectual property (such as money, houses or land) is that the former tend to be what economists call non-rival while the latter tend to be rival. A rival good cannot be used by one without diminishing the ability of another to use it. My consumption of a pizza prevents you from consuming the same pizza. My use of an idea, a design or technique, on the other hand, does not diminish your ability to use that same idea (so long as in implementing the idea I do not use up the only resources available to implement that idea). We can both use the idea of a pizza to make our own individual pizzas without interfering with each other. Such intellectual goods are non-rival – they can be enjoyed by more than one person at the same time without losing value.

This difference is not absolute, however. Some non-intellectual goods are non-rival. Traditional public goods, such as clean air, are non-rival, but they are certainly not intellectual goods. However, most goods that are traditionally the objects of property rights, (money, houses, land) are rival. Similar qualifications apply to intellectual goods, which can sometimes be rival in certain ways. We might call them non-rival in consumption; your ability to consume an intellectual good is not affected by my consuming the same intellectual good. However, your ability to use the good in other ways may be affected by my use of it. My ability to profit from stockmarket tips (which I would classify as intellectual goods) depends on how many other people are using the same tips. My ability to profit from selling you a book depends on whether or not you have already read it. More generally, the ability to profit from an intellectual good is compromised if others are able to consume it for free. However, with these qualifications in mind, two generalisations can be made. Intellectual goods tend to be non-rival, at least in consumption. In contrast, the kind of non-intellectual goods that are typically the objects of property rights – houses, land, vegetables – are rival.

A popular defence of intellectual property takes the maximisation of innovation as the relevant end. This version is assumed in the economic literature and reflected in the wording of United States law on intellectual property:

“to Promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

Another kind of defence takes the protection of individual creator’s rights as the most important thing an intellectual property regime exists to do. According to this view, people have the right to control the things they create with their mind. This includes preventing others from using their ideas.

Economics: the basics, and a digression no comments

I’ve been reading Samuelson’s Economics, a classic introductory textbook. So far I’ve got a better understanding of what economics is about. The essential definition according to Samuelson is that it is ‘the study of how societies use scarce resources to produce valuable commodities and distribute them among different people’. This includes, but is not limited to, the following questions:

• How the prices of labour, capital and land are set, and how they are used to allocate resources

• How the financial markets behave and how they allocate capital to the rest of the economy

• Distribution of income and how the poor might be helped without reducing growth

• Impact of government activities on growth

• Studying swings in production and unemployment and how policies can encourage growth

• International trade

• Growth in developing countries and how to encourage efficient use of resources

Returning to the above definition, we can see that without scarcity – i.e. if there were always enough goods to satisfy every person’s every desire – there would be no need for economics, because everybody could just take what they want and need without depriving anyone else. The desire for efficiency is also essential to economics; if we didn’t care about satisfying as many needs and desires as possible, then we wouldn’t need economics to tell us how to most efficiently distribute scarce resources. The economy is producing efficiently ‘when it cannot increase the economic welfare of one person without making someone else worse off’.

A QUESTION/ DIGRESSION

As an aside, I disagree with / don’t understand this definition. Imagine an economy where most of the resources are in the hands of one person (call him Bill). Imagine, reasonably, that in such an economy no-one’s economic welfare could be increased without making Bill worse off. According to Samuelson’s definition, then, this society is efficient. But surely, you want a notion of efficiency which allows decreases in welfare of one person so long as they result in proportionally greater increases in the welfare of others. If Bill’s income tax for the year is £1 million, and that revenue allows government spending, which stimulates GDP, perhaps it could make 10,000 people £20 richer – a net gain for society. Wouldn’t this be a more efficient use of resources?

From a Google search, I think the notion of ‘pareto-optimal’ captures my pre-theoretical intuition about efficiency – where a pareto-optimal situation is one in which no individual’s welfare can be improved without making another individual’s welfare proportionally even worse off. Imagine that taxing Bill £1 million makes 9,999 other people £10 richer. But this would not count as pareto-optimal, because Bill would have lost more than the combined gains of others (£1 million vs £99,990). That’s what I had imagined an economist’s notion of efficiency referred to, before reading Samuelson. But perhaps I’m jumping the gun here!

…back on topic:

Microeconomics is the study of individual entities such as markets, firms and households. It considers how individual prices are set, the determination of prices of land, labour and capital, and market efficiency.

Macroeconomics came around in the 1930’s when John Maynard Keynes decided to look at the overall performance of the economy. He analysed what causes unemployment and downturns, investment and consumption, the management of money and interest rates by central banks, and why some economies thrive and others fail. These days the distinction between the two is less important, with microeconomics being applied to studying unemployment and inflation.

Economists observe current economic phenomena as well as historic data and make theoretical predictions and broad generalisations on that basis. They also use econometrics, which is the application of statistical analysis to economic data, allowing them to identify the relationships between different factors.

The kind of economy one has depends on three things:

• What goods should be produced

• How should they be produced

• For whom will they be produced

Factors of production are things that are used to create goods and services, and come in three categories:

• Land (and other natural resources)

• Labour – human time

• Capital – goods which can be used to create new goods

Attitudes: Do I have one? no comments

I have found myself in a rather strange territory this week. Under normal circumstances, I would be very offended or at least somewhat disappointed with myself if someone says I have an attitude. Yet, what does the word “attitude” actually means?

“attitudes are defined at least implicitly as responses that locate ‘objects of thought’ on ‘dimensions of judgement’ ” (McGuire, 1985, p.239)

“an attitude is a general and enduring positive or negative feeling about some person, object or issue” (Petty and Cacipoppo, 1996, p.7)

It is interesting to see from this definition that we all have an attitude toward something. It is normal. Most importantly, having an attitude in an academic sense is not wrong. An attitude can be positive or negative. Even negative attitude is not always wrong. For example, having a negative attitude toward murder is generally socially acceptable. This concept of right and wrong, or social acceptance brings us to another closely related topic: Cognition and Behavioural relationship.

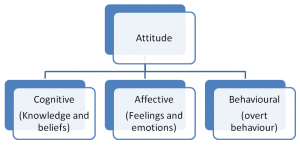

Cognition and Behavioural Relationship

The above model is commonly known as the ABC model for obvious reason. This model was first proposed by Hilgard in 1980 and has since became the fundamental framework for further research. For instance, many have investigated the relationship between behaviour and beliefs. It has been found that behaviours are modified by the peers, identity of self with the peers and perceived social norms.

This is an interesting findings because it backs up the social concept of “peer pressure” and shed light on how these pressures function/ affect an individual. The book then went on to discussion several theories regarding the factors involved, such as: theory of reasoned action, and planned behaviour, social identity, self-categorisation, social norms, group definition and discursive theories.

Time would fail me if I was to detail all of them here. It should be sufficient to say that these theories were used to describe the results obtained from various experiments. It is particularly interesting to see how these theories interact with each other and compliments each other.

Moving On

In view of the time remaining, I will be reading up more on self and identity as I have found this topic rather interesting. That will then be my last post based on text book reading. Further posts will concentrate on multidisciplinary approach and migrate towards final report style thinking/ writing/ blogging.

Economics of Ontologies no comments

Am trying to focus back in on my original assertion about what I was going to study. This was whether there are differences between subjects and their degree of separation from the www, and their primary ontologies. Although I was going to use economics and psychology or perhaps sociology and their attendant ontologies to create a spotlight with which to examine this question, this would still involve looking at the ontologies of a range of other subjects.

Am trying to focus back in on my original assertion about what I was going to study. This was whether there are differences between subjects and their degree of separation from the www, and their primary ontologies. Although I was going to use economics and psychology or perhaps sociology and their attendant ontologies to create a spotlight with which to examine this question, this would still involve looking at the ontologies of a range of other subjects.

I was going to use economics as a focus, as I think it perhaps represents something that might be wrong with how we talk about knowledge in general and reasons for studying, working together, collaborating – ultimately: trust.

A lot of work that we do is tied into research programs that are underwritten by governments as being part of some economic promise. For example, the last Labour government’s education policy was predicated partly on the premise (stemming from research in the 1950s that re-emerged in the 1970s (need to find and cite)) that countries with a more highly educated population tend to do better economically. Thus following Tomlinson’s recommendations, the Diploma system was introduced, only partially, which in fact had the consequence of introducing a system that did the opposite of what he had intended.

This however, being loosely accepted: that the more highly educated a population is, the more wealthy their country, it would seem to follow that it makes sense to make use of emerging technologies to help to educate this population. There is a body of research on this – how technology can be ubiquitous; it can get to the places that teachers can’t, and can help to make learning something that is always ‘on’.

There are actually so many problems with these assertions that it would take a whole other blog post, or perhaps even, essay, or perhaps even, thesis to go into them – but I’m happy to accept that 1) learning is basically a Good Thing and that 2) technology can help to mediate it. I might perhaps then reluctantly accept that it’s possible that if you have a lot of learning, you might end up creating more wealth for your country, however some of the data for this is possibly correlative rather than strongly causal.

But to get back to my original question, it is whether there might be said to be an economics of ontologies? Could we find out whether there are some subjects that lend themselves, via their objects of knowledge to be shared and studied on the web? And that therefore are more accessible and therefore might end up generating more money?

It seems at first glance, that physics might be one of these subjects. Physics research can be large scale and tend to be carried out by large communities who share resources. Is there something about the nature of physics that makes people more likely to collaborate? Are they perhaps true seekers after knowledge who are less motivated by economics / reward than say, chemists? (Apologies to all you pioneering, truth-seeking chemists out there.) Would this then mean that by the very nature of a subject, if it attracts more people who care more about discovery, or truth, then they may well as a result, collaborate more, and could easily use technology in order to do this, but they care less about creating wealth, so that all web-based subjects that can easily or practically use the web to be studied are never going to be worth funding by governments who only care about short-term goals?

This seems on the face of it, rather facile, but it does intersect with another debate about why there still seem to be less girls studying physics, and in general, science subjects. (This debate appears worldwide, but I shall for now confine myself to the UK.) There was recently some speculation about whether the Big Bang Theory was attracting more people to the subject, but this generated some scathing responses from researchers who had determined that take up of physics was in fact governed by early influences.