Archive for the ‘Economics’ Category

Business Economics Week 3 no comments

This week I start by looking at business strategy from the perspective of economics. There are basic economic principles underpinning the determination, choice and evaluation of business strategy.

As mentioned in my post on management studies from a few weeks’ back, right strategies (the ways in which organizations address their fundamental challenges over the medium to long-term) are crucial for businesses to survive and beat the competition. Strategic-minded thinking includes comprehensive consideration and reflection upon a business’ mission statement and its vision. For both economists and management theorists, therefore, the aims of a business determines its strategy. Equally relevant, however, for both disciplines are internal capabilities and industry structure/conditions.

Like management theory, economists adopt Porter’s five forces model of competition (Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, 1980) which set out to identify those factors which are likely to affect an organization’s competitiveness. These five forces are:

• The bargaining power of suppliers

• The bargaining power of buyers

• The threat of potential new entrants

• The threat of substitutes

• The extent of competitive rivalry

I will be returning to these five forces next week in the context of considering, specifically, how they apply to the effects of the Web. In the meantime, it is worth pointing out that the five forces model does have limitations. For example, it is a largely static model whereas conditions change over time requiring strategy to evolve over time. Notably, also, Porter’s model suggests that success is dependent on competition rather than the potential for collaboration and cooperation (such as with those downstream vertically from a supplier).

Value chain analysis is also closely linked to the five forces model (according to the definition of Sloman, Hinde and Garratt, value chain “shows how value is added to a product as it moves through each stage of production from the raw material stage to its purchase by the final consumer”). Analysis of the value chain involves evaluating how each of the various operations within and around an organization contributes to the competitive position of the business). Ultimately it is these value-creating activities, which can be primary or support activities, that shape a firm’s strategic capabilities.

Turning to growth strategy, it is worth making a nod here to vertical integration (this will become more relevant when considering the effects of the Web in facilitating disintermediation of value chains over the next two weeks). There are a variety of reasons why forward or backward vertical integration might lead to cost savings (such as through economies of scope and scale), including: production economies; coordination economies; managerial economies; and financial economies. The major problem with vertical integration as a form of expansion is that the security it gives the business may reduce its ability to respond to changing market demands.

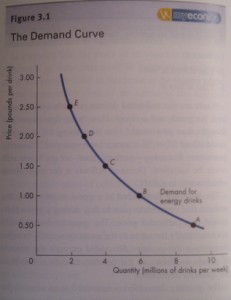

Other points of comparison and dissimilarity between management and economics can start to be drawn. For example, a point of difference is economics’ focus on theories related to short-term/long-term profit maximization. There is much debate among economists about whether profit-maximizing theories of the firm are unrealistic (largely due to a lack of information or lack of motivation). This focus is where costs concepts and graphs (demand curves in particular) come in.

A more practical illustration given by Sloman, Hinde and Garratt in respect of the search for profits is the video games war where there are high costs, but also high rewards, from a long-term perspective. In considering the secret of success in the market, online gaming capability and global connectivity are significant factors. Moreover, connection to the internet has facilitated a move towards the use of consoles as ‘digital entertainment centres’, in which users can download content. These developments are likely to continue as long as broadband internet connectivity improves and remains fairly cheap to use.

Finally, in economics, there are various theories of strategic choice (such as cost leadership, differentiation and focus strategy). These strategies can be combined. For example, Amazon had a clear niche market focus strategy – to sell books at knockdown prices to online customers – and this has become a mass market with the spread of the Web and due to lower costs.

Next week, I want to move the focus firmly onto the impact of the Web on business competition as I move on from broad principles of management/economics to specifics. I will kick off with a consideration of Google’s business model.

Economics of Ontologies no comments

Am trying to focus back in on my original assertion about what I was going to study. This was whether there are differences between subjects and their degree of separation from the www, and their primary ontologies. Although I was going to use economics and psychology or perhaps sociology and their attendant ontologies to create a spotlight with which to examine this question, this would still involve looking at the ontologies of a range of other subjects.

Am trying to focus back in on my original assertion about what I was going to study. This was whether there are differences between subjects and their degree of separation from the www, and their primary ontologies. Although I was going to use economics and psychology or perhaps sociology and their attendant ontologies to create a spotlight with which to examine this question, this would still involve looking at the ontologies of a range of other subjects.

I was going to use economics as a focus, as I think it perhaps represents something that might be wrong with how we talk about knowledge in general and reasons for studying, working together, collaborating – ultimately: trust.

A lot of work that we do is tied into research programs that are underwritten by governments as being part of some economic promise. For example, the last Labour government’s education policy was predicated partly on the premise (stemming from research in the 1950s that re-emerged in the 1970s (need to find and cite)) that countries with a more highly educated population tend to do better economically. Thus following Tomlinson’s recommendations, the Diploma system was introduced, only partially, which in fact had the consequence of introducing a system that did the opposite of what he had intended.

This however, being loosely accepted: that the more highly educated a population is, the more wealthy their country, it would seem to follow that it makes sense to make use of emerging technologies to help to educate this population. There is a body of research on this – how technology can be ubiquitous; it can get to the places that teachers can’t, and can help to make learning something that is always ‘on’.

There are actually so many problems with these assertions that it would take a whole other blog post, or perhaps even, essay, or perhaps even, thesis to go into them – but I’m happy to accept that 1) learning is basically a Good Thing and that 2) technology can help to mediate it. I might perhaps then reluctantly accept that it’s possible that if you have a lot of learning, you might end up creating more wealth for your country, however some of the data for this is possibly correlative rather than strongly causal.

But to get back to my original question, it is whether there might be said to be an economics of ontologies? Could we find out whether there are some subjects that lend themselves, via their objects of knowledge to be shared and studied on the web? And that therefore are more accessible and therefore might end up generating more money?

It seems at first glance, that physics might be one of these subjects. Physics research can be large scale and tend to be carried out by large communities who share resources. Is there something about the nature of physics that makes people more likely to collaborate? Are they perhaps true seekers after knowledge who are less motivated by economics / reward than say, chemists? (Apologies to all you pioneering, truth-seeking chemists out there.) Would this then mean that by the very nature of a subject, if it attracts more people who care more about discovery, or truth, then they may well as a result, collaborate more, and could easily use technology in order to do this, but they care less about creating wealth, so that all web-based subjects that can easily or practically use the web to be studied are never going to be worth funding by governments who only care about short-term goals?

This seems on the face of it, rather facile, but it does intersect with another debate about why there still seem to be less girls studying physics, and in general, science subjects. (This debate appears worldwide, but I shall for now confine myself to the UK.) There was recently some speculation about whether the Big Bang Theory was attracting more people to the subject, but this generated some scathing responses from researchers who had determined that take up of physics was in fact governed by early influences.

Business Economics Week 2 no comments

This week I looked at the workings of competitive markets: first in basics, before turning more specifically to my research question around how the Web has changed competition between businesses from an economic viewpoint. I continue to refer to the Sloman, Hinde and Garratt book, ‘Economics for Business’ (5th ed).

As outlined in my posts on management studies from previous weeks, firms are greatly affected by market environments (particularly when it comes to pricing strategies). The more competitive the market, the greater the domination of the market over firms (e.g. resulting in ‘price takers’ nearer the model of the ‘perfectly competitive’ market when price is entirely outside a firm’s control, rather than ‘price setters’ nearer the model of the monopolistic, ‘imperfect’ market).

Although price is often at the heart of competitive strategy, the significance of non-price factors of competition should also not be underestimated. By differentiating one firm’s products from another’s, such as through design and marketing/advertising, firms seek to influence demand. Of course, the most dramatic growth in advertising expenditure over the last decade or so is on the internet (which increased from virtually nothing in 1998 to nearly 20% of all UK total advertising expenditure in 2008 based on data in the Advertising Strategic Yearbook 2009).

The better a firm’s knowledge of a market, the better it will be able to plan its output to meet demand. In particular, knowledge related to the size and shape of current and future demand choices by consumers is critical to the investment decisions that businesses make (Philip Collins, OFT Chairman, Speech 2009). Such predictions include the strength of demand for a firm’s products followed by responsiveness to any changes in consumer tastes (particularly when the economic environment is uncertain). Collecting data on consumer behavior is therefore highly valued by businesses, assuming it can be analyzed properly so it can be used to estimate price elasticity and forecast market trends and changes in demand. Price elasticity as a concept is the measure of the responsiveness of quantity demanded to a change in price. Methods for measurement include market observations, market surveys and market experiments.

Conversely, consumers face a similar problem when they have imperfect information about, in particular complex, products/services. In finding ways for consumers to trust information provided by sellers, establishing a reputation and third parties helping firms to signal high quality can assist. For example, Sloman, Hinde and Garratt refer to the online auction site eBay providing a feedback system for buyers and sellers so they can register their happiness or otherwise with sales.

The supply side of the market is just as important as the demand side. Businesses can increase their profitability by increasing their revenue or by reducing their costs of production. Both these concepts are subject to economic theorizing to discover the particular output at which profits are maximized. The answer in any one case is heavily dependent on the amount of competition in the market which is measured, in turn, by concentration levels.

E-commerce is a force at work undermining concentration (dominance by large consumers) and bringing more competition to markets. Its effects include:

• Bringing larger numbers of new, small firms to the market (‘business to consumer’/B2C and ‘business to business’/B2B e-commerce models), which can take advantage of lower start-up and marketing costs.

• Opening up competition to global products and prices, resulting in firms’ demand curves becoming more price elastic particularly when transport costs are low.

• Adding to consumer knowledge, through greater price transparency (e.g. through price comparison websites) and online shopping agents giving greater information on product availability and quality.

• Encouraging innovation, which improves product quality and range.

On the other hand, e-commerce disadvantages still include – for example – issues around delivery (such as timing) and payment security. Furthermore, larger producers may still be able to undercut small firms based on low cost savings from economies of scale.

Sloman, Hinde and Garratt provide an interesting case study of the challenges to Microsoft by the antitrust authorities in the EU and the US – something which I am very familiar with as a former competition lawyer. This example is illustrative of the balancing exercise required when assessing the virtues of allowing very large firms to be unfettered in terms of their potential exclusionary practices, versus allowing smaller firms a more even playing field to challenge such large firms which could dampen the latter’s investment in innovation over the long-term.

Of course, new internet-only firms (such as Facebook and Google) have very different business models from that of Microsoft, including the provision of numerous free products as part of a desire to create large networks of users and heavy dependence on tailored advertising revenues.

Next week, I will look at business strategy this time from an economic (rather than management) perspective.

Introducing Business Economics no comments

This week I turn to my second discipline, economics, as a basis for considering a different slant on my research question (how the Web changes competition between businesses). While having some degree of economics knowledge in my background, I have approached the subject area afresh in a systematic fashion with guidance from a book looking at economics for businesses (Sloman, Hinde and Garratt 2010).

My starting position is to look at the essence of economics: how to get the best outcome from limited resources. In other words, economics tackles the problem of scarcity which is a central problem faced by all individuals and societies. Demand and supply and the relationship between them are central to this analysis. Also key is the concept of choice (known as “opportunity cost”): the sacrifice of alternatives in the production or consumption of products or services.

Economics is traditionally divided into two main branches: macroeconomics and microeconomics. Macroeconomics examines the economy as a whole at a national or indeed international level (i.e. aggregate demand and supply), whereas microeconomics examines the individual parts of the economy. The latter includes all the economic factors that are specific to a particular firm operating in its own particular market. As microeconomics explores issues surrounding competition between firms, and due to limits in time, I will not be looking at macroeconomics in any detail (other than indirectly via a general awareness of the factors that affect economies as a whole, which in turn affect individual firms as an important determinant of their profitability).

From a microeconomics perspective, the choices made by firms are studied alongside their results. Such choices include how much to produce, what price to charge, how many inputs to use, what types of inputs to use and in what combinations, how much to invest etc. Making such choices involve rationality in weighing up the marginal benefits versus the marginal costs of each activity to best meet the objectives of the firm.

It is worth pausing at that point to make a comparison between the relevance of economics to business decision-making and the contents of my previous blog posts on management study’s approach to business activities and competition between firms. Both use similar terminology and look to the structure of industry and its importance in determining firms’ behavior. They also both look at ranges of factors that affect business decisions and consider the wider environment in which firms operate (including conditions of competition in relevant markets) in helping to devise appropriate business strategies. For example, Sloman, Hinde and Garratt also refer to how the pace of technological change has had a huge impact on how firms produce products and organize their businesses, together with a ‘PEST’ – political, economic, social and technological – analysis (compare my previous blog entry ‘Management 102’).

Where economics (more specifically, we can call it ‘business economics’) differs from management is its focus on how firms can respond to demand and supply issues. In other words, its emphasis is more on internal decisions of firms related to achieving rationally efficient outcomes and the effects of such decision-making on a firm’s rivals, its customers and the wider public.

In keeping with the theme of efficiency, economics has traditionally considered that business performance should be measured against a structure-conduct-performance (structure affecting conduct affecting performance) paradigm measured by several different indicators. Performance is also determined by a wide range of internal factors and external factors other than just market structure, such as business organization, the aims of owners and managers.

In returning to the theme of how economics differs from management/business studies, economists have traditionally paid little attention to the ways in which firms operate and to the different roles they might take. Firms were often seen merely as organizations for producing output and employing inputs in response to market forces. In other words, virtually no attention was paid to how firm organization and how different forms of organization would influence their behavior. This position has changed as economist interest in firms’ roles with respect to resource allocation and production (and how their internal organization affects their decisions) has increased.

Economists have also conventionally assumed that firms will want to maximize profits. The traditional theory of the firm shows how much output firms should produce and at what price, in order to make as much profit as possible. While it may be reasonable to assume that the owners of firms will want to maximize profits, it is the management (as separate from the shareholders) that normally takes decisions about how much to produce and at what price. Management may be assumed to maximize their own interests, which may conflict with profit maximization by the firm. In summary, the divorce of ownership from control implies that the objectives of owners and managers may diverge and hence the goals of firms may be diverse.

In their introductory section on business and economics, Sloman, Hinde and Garratt include an interesting case study on the changing nature of business in those countries where economies are knowledge driven and innovation is therefore central to business success. They include a quote from a European Commission publication (Innovation Management and the Knowledge-Driven Economy, 2004) on this point:

“With this growth in importance, organisations large and small have begun to re-evaluate their products, their services, even their corporate culture in the attempt to maintain their competitiveness in the global markets of today. The more forward-thinking companies have recognised that only through such root and branch reform can they hope to survive in the face of increasing competition.”

Thus, it is suggested that the dynamics of knowledge economies require a fundamental change in the nature of business. This is an interesting comment in considering the impact of the Web on competition from an economical viewpoint. Knowledge is fundamental to economic success in many industries. The result is a market in knowledge, with knowledge diffusing and cutting across industry boundaries. Another result is the increasing outsourcing of various stages of production and collaborations across industries. Furthermore, whereas in the past businesses controlled information, today access to information via sources such as the Web means that power is shifting towards consumers.

Next week I will turn to the concept of markets from an economic viewpoint and how competition is assessed via the theory of the market.

Interdisciplinarity no comments

Just reading Repko’s book on Interdisciplinary Research. Very interesting to consider that,’ Interdisciplinary research is a decision-making process that is heuristic, iterative, and reflexive. Each of these terms – decision-making, process, heuristic, iterative, and reflexive-requires explanation.’

I’m finding this very intriguing, especially in relation to one of our courseworks that involves outlining the process involved in searching for and (hopefully) finding material on a randomly selected question that has something to do with the web at its heart. It is interesting that although we think of searching as ‘seeking’ there is sometimes an element of filtering or of looking for material that might reinforce one’s original ideas.

Have also been reading on economics in Afghanistan, Intelligent Agents (not secret ones), hypermedia, (just discovered The Humument – an old favourite of mine is about to be released as an app) bots (including narrative bots and social bots – here’s one I made earlier) and privacy. At present these don’t strictly appear to be to do with my original question, but some of the topics keep re-presenting themselves to me and so I’m keeping an eye on them, to see if they might develop into a personal theme. Have also been reading on spimes, hyperreality and skeuomorphs, and came across this blog from Matt Jones on The Internet of Things.

Have a good introduction to Sociology (Giddens) but need to also check to see what isn’t in it, as it’s quite an old copy.

Markets not Stakes… no comments

Am now looking at a book on economics called, ‘Markets not Stakes: The Triumph of Capitalism and the Stakeholder Fallacy.’ This is written by Professor Patrick Minford and was published in 1998. He outlines why he thinks that the stakeholder culture was mistaken and how capitalism was thriving. The stakeholder concept was supposed to find the middle way between ‘failed socialism and free-market capitalism.’ The blurb discusses the way in which regulatory proposals were to create more rights for workers, allow the government to override the pull of market forces on investment in an attempt to curb the 80s short term corporate culture.

Am now looking at a book on economics called, ‘Markets not Stakes: The Triumph of Capitalism and the Stakeholder Fallacy.’ This is written by Professor Patrick Minford and was published in 1998. He outlines why he thinks that the stakeholder culture was mistaken and how capitalism was thriving. The stakeholder concept was supposed to find the middle way between ‘failed socialism and free-market capitalism.’ The blurb discusses the way in which regulatory proposals were to create more rights for workers, allow the government to override the pull of market forces on investment in an attempt to curb the 80s short term corporate culture.

I am particularly interested in this because it would seem very easy now to say how obviously mistaken this view was. However, it goes on to say that ‘Stakeholding is no different in essence from interventionist and redistributive taxation, its only difference is its lesser transparency, which therefore deceives people into believing it to be innocuous.’ Although he then apparently goes onto argue that it destroys incentives (the meat and blood of economics, according to ‘The Armchair Economist’ ) I’m initially quite interested in the transparency issue.

When I worked for a FTSE100 company that was quite concerned about corporate governance and hence ‘transparency,’ a word which we hear all too often nowadays, the other word that was always brandished was ‘stakeholders.’ Generally the more your job was to do with explaining figures and processes to people, the more you had to take ‘stakeholders’ into account. This actually meant not just anyone who had a right of some sort (surely just one’s bosses in a monolithically hierarchical company structure?) to poke their nose into what was going on, but those who felt that they ought to have a right. Or those, like me, who were just very, very curious about how it all worked. The more stakeholders there were (in a PLC serving most of the country’s households, that was at least 18 million) actually the less possible it became to be transparent. I’m increasingly convinced that the possibility of transparency decreases exponentially in any very small company (say, 7 or fewer employees) or any company that has over say, 300 employees, just because of organisational factors. I’m also wondering whether this is not accidental, but actually deeply tied into company size (depending on its structure, or how the power gets passed around). So am quite interested to read this book and see what comes out.

Am reading it alongside ‘The Armchair Economist’ which is interesting, but is leaving me feeling vaguely unsatisfied at present.

Basic concepts: Economics no comments

“A social science what studies the choices individuals, businesses, governments and entire societies make as they cope with scarcity and the incentives that influence.” Scarcity refers to not having enough money for food, or the inability to do something that you want to do because you have to work. We all face scarcity, but we need to make choices to cope with it, for example, choosing to work over choosing a fun activity because you need the money from working to pay bills. The choices we make are influenced by incentives. It can take the form of a reward or a penalty. If skipping work has a good opportunity of getting a much better job we may be more likely to choose to skip work. This is a just a very simple example, but it also works on a larger scale. If the price of computers drops we may as a society decide to buy more and furnish all schools with good computers.

Economics is a large area is we take into consideration individuals, businesses and entire societies; therefore it is broken up into Microeconomics (individuals and business choices) and Macroeconomics (national and global economy).

One of the most common economic phrases is “supply and demand”. Demand refers to the relationship between how many people want a product and how much it costs. Supply refers to the relationship between the quantity of the product created and its price. An increase in demand would mean an increase in price and quantity supplied. An increase in supply would mean a decrease in price and increase in quantity required.

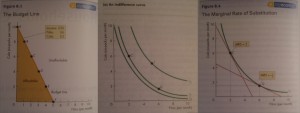

Household consumption choices are limited by income. The budget line is a way of seeing income that can be spent and how it can be spent. If prices of items you buy drop or income increases the Budget Line will change.

Indifference curves are used to show within what combinations of goods the consumer is indifferent to having. For example someone may not mind swapping a packet of cigarettes for an extra drink at the bar or even extra chocolate during the week at work.

Marginal Rate of Substitution is the rate someone will give up n of x to get n of y. If the rate is high an individual will give up a large quantity of x for a small quantity of y. This works the other way round if the rate is low, they will only give up a small quantity of x for a large quantity of y. However, we must be aware that the substitution must compliment or be a fair substitute for the item. If you are very thirsty and are offered a truck load of peanuts for one can of drink you may still decide to keep the drink!

By using these three ideas we can develop a model to predict consumer behaviour. We assume someone will pick the point that benefits them the most, so if it fits inside the budget line (indicating it is affordable) and it lies on the indifference curve (indicating it is a option someone would be happy with) and has a marginal rate of substitution that is equal to the relative price of the items desired, this gives the most affordable point and hopefully that is what someone would choose.

Elasticity is the measurement of how variables can affect each other. An example would be lowering prices to sell more.

Market power refers to the ability to influence the market. A monopoly is when a company has goods or services with no close substitute and has a barrier stopping other companies selling similar products or services. An example would be energy suppliers or the Post Office. Barriers stopping other companies could be a government contract or patent or copyright issues.

Advertising increases total cost of a product, but if the advertising increases sales the total cost of a product will fall.

Uncertainty and Risk

Uncertainty is linked to how certain you are of an event occurring. For example a farmer can never be certain crops planted will grow because they cannot be certain of the weather and other factors that could affect crop growth. Risk is a situation where more than one outcome may occur and the probability of those happening. Probability can be measured accurately or we may have to look at past experience and make a judgement called subjective probability. The cost of risk can be accessed from these probabilities. A person’s attitude towards risk can be assessed using their wealth and how much utility someone attaches to a given amount of wealth. The more wealth you have the higher the utility and the larger risks can be made.

Microeconomics

If the aim of a company is to maximise profit. They can be in any of the below modes of operation:

- Make an economic profit (average total cost is less than the price of each product)

- Make a normal profit (where economic profit is zero)

- If the price is between average total cost and average variable cost the company is loss-minimising. By continuing to produce it may still recover, if it stops it will lose money.

- If the price is below the average variable cost the company should go into shutdown. Losses are minimised by not producing more (wasting money of products that are selling at a loss).

Information and graphs summarised from:

Parkin, M., Powell, M., & Matthews, K. (2008). Economics. Essex, England: Pearson Education Limited.

.

From a Psychology background I can’t help but stick this in to reflect upon. In order to utilise economics you are assuming that the consumer or the company has the aim of maximising profits and that they will always make the best rational decision. However, luck and cognitive dissonance may be more of a factor than simply “working out the numbers”. Daniel Kahneman: How cognitive illusions blind us to reason.

The Pit and the Pendulum of extended and over-elaborate metaphor no comments

Mors ubi dira fuit vita salusque patent.

So, to expand the first blog post a little: what I think is nagging at me is this sense of a range of ‘objects,’ of pieces of ‘knowledge-meat’, or ‘currency’, that are consumed or traded within their own disciplines. Sometimes these objects of knowledge have the same names in other subjects, but they mean different things. And across disciplines the means of making them edible, civilized, tradable can be hugely different. Traditionally these bits of ontologies, of data (they are sometimes data) are going to somehow be examined, discussed, prodded, perhaps measured: quantified or qualified in some sense. In the past this might have been described on paper. These days, some of us (perhaps not that many, globally) have the web as a means of mediating discovery and knowledge acquisition. There are many things that can be done with knowledge on the web: it can be hidden, it can be spread, it can be created, it can be pushed around. If tiny bits of data somehow fit with the tiny little pieces of the structure of the web, then one might suppose that a sort of true picture emerges. However, again, something that has nagged at me is how so much of our thinking is analogical, or metaphorical. So that true pictures are actually very hard to locate using reductionist mapping – see Wicked Problems, for example.

What I think might be part of one of the questions I want to pursue, is to do with how the web might change the analogies that are implicit or embedded within disciplines. Sometimes the process of collaboration can bring out these assumptions. Sometimes, collaboration is hugely impeded by them.

For example, one of our widely used assumptions or analogies that fascinates me, is that which describes electricity. Electricity has long been portrayed as a commodity. Walter Patterson (a physicist by trade) has written at length on this subject, in a book called, ‘Keeping the Lights On.’ The traditional picture of electricity is of something that ‘flows’ like water, and can be cut off, traded, conserved, or wasted. Entire forests have been destroyed in the pursuit of the subject of electricity and our consumption of it. Generations of schoolchildren have suffered sleepless nights, worrying (somewhat misguidedly) about global warming’s fatal pendulum hanging over the Polar Bear every time they put their heating on (along with the location of the calorie – another rather elusive and misleading concept.)

Patterson says, “How many times have you heard or read some energy specialist refer to ‘energy production’ or ‘energy consumption’? These people are supposed to be experts. Surely they ought to know one unbreakable law, the First Law of Thermodynamics, the law of conservation of energy. No one produces energy. No one consumes energy. The amount of energy in the whole universe remains the same.”

He then goes on to describes a host of assumptions that arise incorrectly out of our making electricity a commodity to be traded, the most simple being that arising from the regulators who are allegedly looking for the best deal for the household market – a low unit price does not equal a low bill – the holy grail for the ‘consumers.’ To me, having worked with the UK’s largest energy company and, in particular, with their hard and soft data, it’s clear on a fairly elementary level that describing our relationship with electricity like this is going to cause anxiety for the ‘consumer’. It describes a selfish market. It’s all about measuring how much we use, and not the quality of our relationship with it. Too much = red, not very much = green. It’s almost a little bit childish. Imagine designing an app to somehow map our relationship with energy. It would have reds and greens, wouldn’t it? It would be about ‘a lot’ (scolding) or ‘a little’ (caressing tone of voice- well done.) It would be great to break from this model and look at different ways of being technical about how we are with energy.

Even as I’m doing my preliminary, slightly distracted, coffee-table pre-reading, this strikes a chord with me. A book I picked up a couple of weeks ago, written by Stephen Landsburg is called, ‘The Armchair Economist.’ (In the manner of many inhabitants of armchairs he keeps disappearing just when I want him. I’m also wondering if The Spy in the Coffee Machine can see him from the kitchen, and if so, whether they should talk. Never mind.)

The first chapter of this book starts boldly with, “Most of economics can be measured in four words: ‘People respond to incentives.’ The rest is commentary.” He then goes on to describe, or perhaps, hypothesise, how making cars more safe kills more people, as people drive more safely in more dangerous cars. Landsburg continues by saying that economics begins with the assumption that all human behaviour is rational. I’m presuming that part of the rest of the book is to decry this notion triumphantly. It is very fashionable nowadays (and seems to cause great joy for the evolutionary psychologists) to show how entirely irrational we are; however I can’t help feeling that there is sometimes a confusion in the literature between say a system of perception, or of governance that overcorrects, and the net result that that has for the movement and/or survival of its owner. (I know, feeling something isn’t really academic: it’s another question to explore.)

So, now I have economics and markets intruding a little into my original speculation about how the concepts or metaphors embedded in disciplines might be creating pictures that aren’t entirely correct. It’s certainly the case that while markets have their own language, they also trade in the languages used by the disciplines that come together to create the products or objects on sale. And now, for some of us, the sorts of things that can be traded, over the net for example, are elusive objects, which it might be worth while trying to pin down a little further. I’m worrying that some of this sounds as though I’m just talking semantics. I do intend to explore this further and show how it’s not just trivial misunderstandings, but deep ones that maybe re-cast our notion of the world to some extent.

As far as a methodology goes, my approach to research is often about contingency. Particularly interdisciplinary research. I don’t believe that using a wholly empirical, top-down filtering method is always going to work, as this assumes that there is an explicit pool of knowledge out there to be refined. My very subject matter says that this might not be the case. So, although I intend to use the traditional method, and my next step is to get my text books on economics and psychology/ sociology, and to read and annotate findings from them, I will also read a lot of not-quite academic, coffee-table stuff that gives me a feel for whether I would be happy to say, sit and have lunch with the people who are writing. And, more immediately, I’m suffering from a nagging sense of not having figured out what the correct referencing procedure for blogging is. I’m used to using hyperlinks and checking they’re still live every now and then. Suspect I might need proper references.

I also haven’t yet drawn out my reasons for an interest in psychology, but, quickly, this is because I think that in the pursuit of truth (which should arise somewhere when looking at how subjects are affected by the web), it is is probably going to be interesting to look at what drives people to co-operate and trust each other when working together within specific subject areas that use specific ontologies that might or might not be affected by the emergence of the WWW.

I am now releasing these thoughts into the wild, where they can roam about in a sort of purgatory of waiting for approval.

Self and business in social networks no comments

I was considering the two topics – social networks and consciousness from the perspective of Psychology and Marketing. But as I found later the more appropriate fields would be Sociology and Social Marketing.

After the class on Wednesday, one nice colleague boroughed me the book Social Psychology by Brehm, Kassin, Fein with the suggestion that I could also look into Sociology. As I was reading through this book and thinking about the topics, I came across the The Self-Concept which is just another term for self-consciousness. We can describe self-consciousness by looking at the main methods through it is achieved:

- introspection = looking inward at one’s thoughts and feelings

- perceptions of our own behavior = analyzing your own behaviour you can find out how you react in certain situations

- influences of other people = identifying yourself through comparison with others

- cultural perspectives – depending on the origin of the individual he might be an individualist (its values are independence, autonomy, self-reliance) or a collectivist (its values are interdependence, cooperation and social harmony)

So point 3. states that self-consciousness is influenced by others. In the Royal Society presentation called Understanding social and information networks given by Professor Jon Kleinberg: http://royalsociety.tv/rsPlayer.aspx?presentationid=499 the speaker shows the probability of joining a group based on the number of friends already joined:

The web is now a social phenomenon, it isn’t just a place to access and share information, it is a world of its own where people interact, live and change. This is an unprecedented phenomenon in human history.

And as the world changes, the way of doing business also shifts from the traditional marketing techniques to a more valuable, customized approach. A suitable quote from Socialnomics by Erik Qualman would be the following:

Marketer’s Philosophy Yesterday

- It’s all about the sex and sizzle of the message and brand imagery

- It’s all about the message; good marketers can sell anything

- We know what is right for the customer – we are doing the customer a service because they really don’t know what they want

Marketer’s Philosophy Today

- It’s important to listen and respond to customer needs

- It’s all about the product; it’s necessary to in constant communication with all the other departments

- We never know what is exactly right for the customer; that is why we are constantly asking and making adjustments

The topics that I touched in this post (and will in the next ones) were the self-concept and how it relates to the social-self, new ways of doing marketing taking into account this new type of individual. Until the next post, I will

- have a look into Sociology to understand the driving forces of social networks

- read more from the book Socialnomics because it describes how social media transforms the way we live and do business (this is actually the book subtitle)

- look into more social marketing books to find out the methods of doing business in this brave new world

Research Question and Chosen Disciplines no comments

My research question is: How has the Web affected the rise and fall of small bands/independent musicians?

Two disciplines: Economics and Sociology

The Web has a large influence on the popularity and reach of music, this is true now more than in previous decades. In terms of Economics I will be exploring how the Web has improved the access to consumers and how this has affected small bands. In terms of Sociology, the Web is not just useful for providing products to a large group of people, it is also used to build social networks which may have an impact on small bands.

The reason behind choosing these two disciplines is that money and society are two large factors in how much an independent musician can ‘achieve’. Using Economics, I will explore how social networks interact with the current economic models for pricing and making profit for the bands. Using Sociology, I will examine the idea that social networks allow larger connection of music fans to each other and to the bands that they are fans of. I will also explore how social networking impacts on the bands’ popularity and reach.

In order to start researching these topics I have visited the library and borrowed introductory textbooks on both Economics and Sociology.