Economic Fundament no comments

Having now covered the beginnings of Politics, I turn to Economics (with cyber-warfare ever in mind). To begin my studies in this subject I’m using the text book Foundations of Economics by Andrew Gillespie, which has so far been a reasonably pleasant, if not too challenging read. The book is split in to two sections – one on microeconomics (dealing with firms and individuals etc.) and the other macroeconomics (inflation, economic growth and international trade etc.) I suspect as I delve further into the subject I will focus more on macroeconomics as this is where the economics of warfare and international relationships come into play, and therefore may be the most effected by cyber-warfare. However before I can gain a proper understanding of this, I need to understand some economic fundamentals.

The first thing to understand is what is the problem that led to the birth of economics in the first place (what with economics being a man-made science). The main issue at the heart of economics is that we have infinite wants, but only finite resources with which to satisfy them. Therefore decisions have to be made (along with some sacrifices) and this applies to both individuals and, more conventionally, countries as a whole. Economies in general have 4 resources with which to work with…

1) Land: The physical land along with its minerals (for example oil or diamonds).

2) Labour: Number of people willing and able to work along with the skills they have. It is also important to consider here the value of knowledge and the effects of increasing it or sharing it.

3) Capital: Quantity and quality of capital equipment such as machinery and infrastructure.

4) Entrepreneurship: Ability of managers to think of new ideas and to take risks.

(With cyber-warfare in mind, 2 and 3 (and possibly 4) seem like the most important resources for this issue.)

Now we know what an economy has to work with, a number of decisions have to be made…

1) What is to be produced?

2) How to produce?

3) Who to produce for?

Naturally we can’t produce everything, in a manner that creates the best products all round and can be distributed to everyone. Therefore the problem of opportunity cost arises, that is to say what could be achieved in the next-best alternative? What do we forgo by acting in this way? Nevertheless these questions need answers and there are two diametrically opposed models for answering them: planned economies and the free market.

In a planned economy the government decides what goods and services should be produced, what combination of labour and capital should be used for any given industry and how the goods and services should be distributed. This however can lead to many inefficiencies, with the government not only having to gather lots of information as to what they need to do, but also actually going ahead and making the right decisions – they could easily produce the wrong quantity of a particular good or service. Similarly they have no pressure to run efficiently as the consumers of the goods and services have no alternative sources, which leads us on to free markets.

In the free market, the aforementioned questions are answered by the interactions of the market forces supply and demand. The government does not intervene and leaves decisions to be made by firms and individuals. If there is demand for a good and a firm can produce it, and still make profit, then it will go ahead and start producing. Only what is demanded gets produced due to a firm’s desire to make profit and there is an incentive to act efficiently as firms are competing against rivals, with all firms in the market wishing to maximise profits. However, this model also has its problems – mainly that a profit cannot be made from providing many goods and services and yet these goods and services may be required. Therefore the government may need to step in and provide certain essential public goods such as street lighting, or, more importantly, education or health services. On the other hand, the free market may find a profit in providing goods, undesired by society as a whole such as guns or illegal drugs.

Therefore in reality, economies are neither completely free market nor completely planned, they include elements of both. Bringing this make to cyber-warfare, one wonders under which category it may fall in the future. If a country wishes to carry out a cyber-based attack on another – does this fall within something the government provides as is the case with conventional armies, or it could it simply outsource the problem to a more efficient company with its own private ‘cyber-army’? Also, to bring this down from an international level, could cyber-warfare play a part in industrial espionage/sabotage? A powerful company in one market, may be able to stop smaller companies entering the market using a cyber-attack or harm its rivals already in the market. With cyber-warfare being so unlike traditional warfare in that it is much cheaper and less violent, companies could quite easily partake.

Back to Economics, another concept that is heavily drawn upon is that or marginal cost/benefit. This concept rather simplifies the process of making decisions: if the marginal cost of something is greater than the marginal benefit then don’t do it (although I suppose the problem lies in measuring the cost and benefit and trying to determine which is greater). This type of thinking may be taken into account when considering cyber-warfare however, with the marginal cost of cyber-warfare being much less than that of conventional forces – is the marginal benefit just as good however (e.g. key infrastructure could be taken out using either cyber or conventional means). Also if the marginal cost of warfare is much greater than the marginal benefit, this does not mean the warfare has to stop altogether, the costs could simply be rearranged so that it is at least equal to the benefit – cyber warfare may be a means to achieve this. (I feel I should point out at this point, I am not an advocate for warfare, but I am trying to see the situation from a warring economy’s point of view. In most situations the best way of reducing the cost of the war would be to end it!)

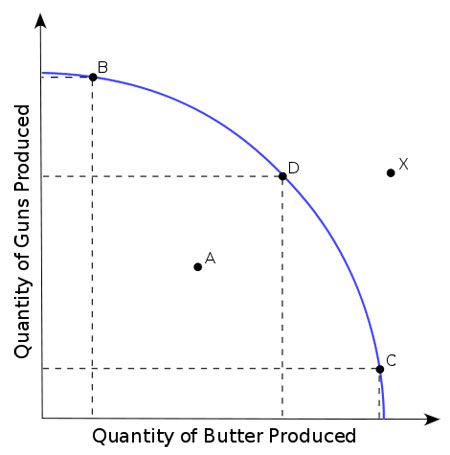

The final concept covered by my readings thus far is that of the production possibility frontier (PPF), a graph which shows rates of production for two different goods or services and how overall production changes when resources are shifted from the production of one to another. An example of a PPF is shown below (image taken from Wikipedia):

All points on the curve can be described as productively efficient. When the quantity of guns produced is decreased, the resources previously used can be reallocated, resulting in an increase in the production of butter. However a contradiction emerges here – gun making resources do not make butter. Therefore if the quantity of gun production lowers to that of point A, the quantity of butter produced may only be at point A and the economy operates within the PPF curve, representing productive inefficiency.

The PPF can also represent the advantages of international trade. Say, for example, the economy above is more efficient at creating guns rather than butter. If it reduces the production of guns by 10, the increase in butter may only be 5. However supposing another economy is more efficient at producing butter than guns; the 10 guns could then be sold on to the other economy instead in exchange for, say, 20 units of butter. This allows an economy to operate outside the PPF, as represented by point X. From the cyber-warfare point of view, could cyber-warfare be a service that one country exports to another? (political allegiances would also most likely come into play here.)

The PPF does not always have to be a curve either. The curve represents diminishing returns, with the amount you get from reallocating resources, decreasing the more you shift from one form of production to another. Straight curves are also possible to represent a constant rate of return. PPF curves are also able to shift either to the right or left, depending on a number of different factors. For example, resources can be taken out of production and invested to increase the productive capacity of the economy in the long run. Immigration can also shift the curve to the right, representing increased labour resources. Effects of cyber-warfare however may result in the curve shifting to the left!

This marks the end of my initial readings in Economics and although so far i have only covered the most fundamental concepts in Economics, ideas about the potential use and advantages/disadvantages of cyber-warfare are already starting to emerge. Next time I shall return to Politics…