Archive for October, 2013

MOOConomics no comments

After reading Winner’s (1980) article ‘Do artefacts have politics’ in our FoWS class, it seemed worth trying to think about MOOCs (as a technical artefact) and the way that they might influence or even determine future methods of delivering education. If I am to address the question of who benefits from MOOCs, then the political aspects or implications of their potential proliferation might be important. However, I’ve just found a rather scathing response (Joerges, 1999) to Winner in the journal Social Studies of Science. It’s full of some pretty impenetrable jargon (for me, anyway), but it might help develop my currently quite shallow understanding of this topic if I can get my head round it.

It has been suggested (by Wendy Hall and Johanna W. during our tutorial) that provision of some kinds of services over the Web tend to be dominated by large entities (such as Facebook, Amazon, or eBay). It may be likely, then, that organisations which already have a strong brand (iTunesU, Google, or well-established universities) may achieve a position of dominance in the provision of MOOCs – perhaps by attracting the ‘biggest names’ in education or industries related to particular subject areas. It’s possible that monopolies or oligopolies will emerge – the start-up costs for some kinds of MOOCs are not insignificant, and such courses do require ongoing allocation of resources, maintenance, and of course regular updating (to contain cutting edge knowledge). It seems unlikely that all education providers will be able to compete on MOOC projects which have, to say the least, intangible returns.

Some further questions might arise from this:

- Is it possible to have ‘monopolies’ in education (are universities public or private bodies these days)? If so, how would such monopolies be defined, and to what extent does the government have authority to make policy/enact legislation to address this issue?

- Should individual universities opt out of the MOOC development process, and invest resources in other areas in which they may be able to compete more effectively?

- Is this an area where consideration of economic ‘opportunity costs’ are relevant, where weighing up the costs of MOOCs against the ‘next best alternative’ determines the outcome?

Looking more broadly at the assignment overall, I’m a little concerned about the potential to combine the thinking behind my two chosen disciplines. One (economics) is built on the basic assumption that human material wants are unlimited, and everyone is motivated by the satisfaction of those wants in conditions of scarcity of resources. Philosophy, on the other hand, contemplates the nature of being, knowledge, truth, right and wrong and other lofty matters. It seems like an ultimate fighting match between a hungry 2-year-old and a Buddhist monk.

In other news, this week I’ve mostly been reading about the fundamentals of economics, about which I will post soon-ish.

References

Joerges, B. (1999) Do politics have artefacts. Social Studies of Science. 29 (3) pp. 411-431

Sloman, J.(2009) Economics (8th edn.). Pearson: Harlow

Winner, L. Do artefacts have politics? Daedelus. 1 pp. 121-136

Ethnography 1 – Introduction & Definition no comments

Researcher: Jo Munson

Title: Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?

Disciplines: Economics, Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

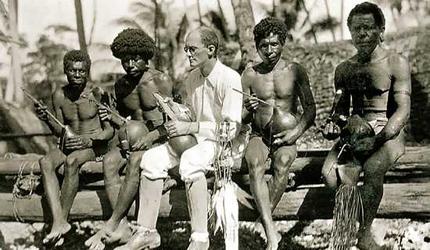

The archetypal vision of Anthropological fieldwork – but times have changed…

A very brief introduction to Anthropology

Cultural Anthropology forms one of the 5 pillars of the broader field of Anthropology, namely:

- Physical Anthropology (also called Biological Anthropology)

- Archaeology

- Anthropological Linguistics

- Applied Anthropology

- Ethnography (Also known as Cultural Anthropology Social Anthropology1)

Common to all Anthropologists is their fascination with human kind.

The scope of Anthropological study is enormous:

- Physical Anthropologists focus on the evolution of our species and the anatomical differences between different races;

- Archaeologists lean towards analysing humans through the material remains we leave; and

- Anthropological Linguists are interested in how our use of language reflects our view of our surroundings, our social hierarchy and social interactions.

Regardless of the application or particular nuance each sub field takes on, the focus is always on finding out more about human beings.

The traditional view of the Anthropologist in the field is the Caucasian middle-aged man living among the tribal peoples of Africa, but this no longer reflects the discipline.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, there began a shift from (predominantly Euro-American Anthropologists) exclusively studying pre-industrial, non-western populations to the study of cultures “closer to home”. The shift reflected the realisation that Anthropologists offer unique insights to society as a whole, not covered by fields such as Sociology. Further more, Anthropology has begun to gain credibility as an applied discipline useful in solving “real world” problems, no longer confined to the realms of academia.

What then, are the particular features that define Ethnography?

[1] Strictly speaking, many argue that Social Anthropology is distinct from Cultural Anthropology. The distinction is not universally defined but some suggest that historically, US Anthropologists have focused more on cultural differences between populations (and commonly adopt the term Cultural Anthropology), whilst UK Anthropologist look more at societal differences (and more commonly use the term Social Anthropology).

Definition: Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

Ethnography has been defined as “the study of contemporary and recent human societies and cultures.” where the concept and diversity of culture is central to Ethnographic study. It is further suggested that:

Describing and attempting to understand and explain this cultural diversity of one of [Ethnographers’] major objective. Making the public aware and tolerant of the cultural differences that exist within humanity is another mission of Ethnology.

I think this summarises the objectives of Ethnography clearly, although does lead me to ask what “culture” is to an Ethnographer.

Anthropological definition of culture

Culture has been defined in countless ways by Anthropologists. One formal definition that has been suggested is that:

Culture is the socially transmitted knowledge and behavioural patterns shared by some group of people

That is to say that culture is not defined by biology or race, but is defined by the environment in which we live. Culture is learned from other people in our social group, knowledge is shared such that the group can reproduce and understand one another and behavioural patterns are assumed such that the group functions well, with each member playing their role.

Culture is of course a far more complex concept than described above, but this gives an idea about what is important to an Ethnographer’s studies. In essence, the Ethnographer studies what is important to the human and the human’s social group, including what allows the group to function and what might challenge harmony within the group.

Next time (and beyond)…

The order/form of these may alter, but broadly, I will be covering the following in the proceeding weeks:

Can there ever be a “cohesive global web”?Ethnography 1 – Introduction & Definition- Ethnography 2 – Disciplinary Approach

- Ethnography 3 – Theories & Methodologies

- Economics 1 – Introduction & Definition

- Economics 2 – Disciplinary Approach

- Economics 3 – Theories & Methodologies

- Ethnographic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

- Ethno-Economic Approach to the “Cohesive Global Web”

Sources

Peoples, J. and Bailey, G. 1997. Humanity. Belmont, CA: West/Wadsworth.

Barnard, A. 2000. Social anthropology. Taunton: Studymates.

Image retrieved from: http://sumananthromaterials.blogspot.co.uk/2010/06/social-and-cultural-anthropology.html

Discipline One: Anthropology no comments

What is anthropology and what do anthropologists do?

Anthropologists can study just about anything that involves human behaviour. Strange (2009) states that the broadest definition of anthropology classes it as a social science involving the study of human groups and their behaviour, their interactions with each other and their physical environments.

Anthropology can also interact with many other disciplines; such as archaeology and the study of past societies, or in studying contemporary societies an anthropologist can sit alongside sociologists and psychologists to employ more quantitative methods or focus more on individuals.

Anthropology is therefore a very broad discipline with large sub-disciplinary areas – such as social anthropology, cultural anthropology, political anthropology, the anthropology of religion, environmental anthropology… basically, if it exists, anthropologists can study it.

It might seem as if nothing can unite this diversity but anthropology is holistic at heart, attempting to place whatever behaviour it examines within its social and environmental context. By nature, anthropology also aims to be very in-depth to fully understand the full range of people’s lives. To do this it relies on data collected in the field and since this is often hard to operationalize and measure, anthropology tends to be more qualitative, often employing the methodology known as ethnography to study its participants. Ethnography creates a portrait of a group and its dynamics – looking at the groups history and composition, its institutions and belief systems.

Therefore, anthropology attempts to account for the social and cultural variation in the world but a crucial part of the discipline is centred around conceptualising and understanding similarities between social systems and human relationships – therefore anthropologists ‘ask large questions while at the same time draw on the important insights of small places’ (Eriksen, 2010:2).

References:

Eriksen, T H (2010) Small Places, Large Issues: An Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology London: Pluto Press

Strang, V (2009) What Anthropologists Do Oxford: Berg

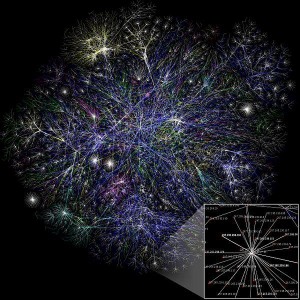

Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”? no comments

Researcher: Jo Munson

Title: Can there ever be a “Cohesive Global Web”?

Disciplines: Economics, Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology)

Is now the time for a transparency and global cooperation on the web?

Can there ever be a “cohesive global web”?

The web is more a social creation than a technical one. I designed it for a social effect — to help people work together — and not as a technical toy. The ultimate goal of the Web is to support and improve our weblike existence in the world. We clump into families, associations, and companies. We develop trust across the miles and distrust around the corner.

A hopeful inditement of the web’s potential from the “father of the web”, Sir Tim Berners Lee (Tim BL), but unfortunately, we are developing mistrust on the web. Whether or not it was the intention of Tim BL and other pioneers of the internet and the web, the power over the infrastructure and development of the web has long been routed in the Western English speaking world.

As the rest of the world has begun to engage with, depend upon and contribute to the web, the US/UK-centric view of the web is being challenged. This distrust for a web where 80% of web traffic is passed through US servers is not limited to the likes of the ever elusive and separatist nations such as North Korea, but by some of the largest economies in the world. Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff voiced her dismay at the NSA’s “miuse” of the web to spy on her private email and correspondence and duly threatened to install Fibre-optic submarine cables that link Brazil directly with Europe, bypassing the current connection via a single building in Miami. German, Mexican and French leaders are also outraged by being victims of the NSA’s “snooping”.

The world’s second largest economy, China, has long dissociated itself from the outside web and US ogliopolistic companies such as Facebook and Twitter, through the implementation of its “Great Fire Wall”. Whilst on the one hand Westerners may view such measures as restrictive, perhaps there is a protective element to such actions that in retrospect, we too may have aspired to.

Discontinuity in global web use is often far less politically motivated and often evades our press. It may shock you to know that Google is not the search engine of choice in some of the world’s most technologically advanced nations. This reaslisation leads me to wonder how other cultures use the web, how can the web work better for them? is the web fit for purpose to move into frontier nations where literacy is far from universal and the concerns rather more fundamental than a 140-character regurgitation of our lunch can cater for?

Why would we want a cohesive global web anyway?

I believe that for the web to establish harmony and be “fit for purpose” as it expands and develops into a global phenomenon, it will have to become more representative of its diverse user base. It seems to me that there are a great deal of reasons why having a cohesive centrally governed (or at least cooperatively governed) web would benefit global society, examples include:

- Economic growth / stability

- Social & political stability

- A more diverse pool of ideas / talent for invention and innovation

- Increased collaboration across nations

- Increased tolerance of other cultures

- Improved security & safety

- Improved use as a tool to combat poverty

- Improved cross-cultural communication

However, the world has had a fractious history – is it therefore too much to hope that the web could transcend our propensity to be territorial and militant? What else might the web be destined for if it cannot sit comfortably within a global society?

The aim of my report will be to assess how two distinct disciplines would approach the feasibility of a "cohesive global web" and how they might come together to approach the problem from a multidisciplinary perspective. I have chosen the following disciplines for my review:

- Economics – primarily because I believe that Economics can be seen in a wealth of our current usage and the “cost benefit” argument seems to play a big role in whether we choose to collaborate / engage with a concept.

- Ethnography (Cultural Anthropology) – because I believe we will only make progress with the concept of a cohesive global web by moving away from our Anglo-centric view and observing the thoughts and experiences of other cultures.

Next steps…

My understanding of both fields is currently naïve at best, so I am excited to discover how the two fields will affect my perspective, and how they will come together to form a research methodology for looking at the future cohesiveness of the web. In the next week I will be compiling a to do list for the remainder of the semester and beginning to delve into my disciplines of choice.

Sources

Nytimes.com. 2013. Log In – The New York Times. [online] Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/14/business/international/google-jousts-with-south-koreas-piecemeal-internet-rules.html?_r=0 [Accessed: 23 Oct 2013]

The Verge. 2013. Cutting the cord: Brazil’s bold plan to combat the NSA. [online] Available at: http://www.theverge.com/2013/9/25/4769534/brazil-to-build-internet-cable-to-avoid-us-nsa-spying [Accessed: 23 Oct 2013]

Heine, J. 2013. Beyond the Brazil-U.S spat. [online] Available at: http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/beyond-the-brazilus-spat/article5186893.ece [Accessed: 23 Oct 2013]

Illustration: Gade, S. Retrieved from: http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/beyond-the-brazilus-spat/article5186893.ece

What is Anthropology? Part 1: Introduction no comments

Eriksen, T. H., 2004. What is Anthropology. London: Pluto Press.

Fieldwork

Although they “cast their net far and wide” (to provide context for observations), the work of the anthropologist is undertaken primarily through close interaction with individuals and the groups they live within. In-depth, structured interviews are used extensively and the key research method is ‘participant observation’ – the goal being to extensively record everyday experiences.

Concepts and theoretical approaches

Observation and reporting is influenced by the interplay between theories, concepts and methodologies.

Key concepts:

1. Language The human perception of the world is primarily shaped by language. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis proposes that language is a strong indicator of the world view that different groups inhabit. Studying the language structure (e.g. predominant use of grammar) can provide a good understanding of a particular groups’ everyday concerns.

2. Theories of the person

a) Egocentric. Person as a unique individual, whole and indivisible; responsible for the decisions they take.

b) Sociocentric. Person as a part of a community, who is a re-creation of an earlier human entity and has a pre-ordained role as a member of a social strata within the community (caste). A persons life is decided by fate and destiny (karma and dharma).

c) Ancestor-centric. Person as a unique individual with personal responsibility, but guided by ancestral spirits.

d) Relational. Person is primarily understood through their relationship with others.

e) Gender. The social construction of male/female distinctions, often described through the idiom of female oppression. Perception of oppression is based on personal appreciation. Male domination of formal economy is prevalent, with women exerting “considerable” informal power. Societies experiencing change often demonstrate conflict and tensions through gender and generational relations.

3) Theories of society

Often related to nation state. But each state contains communities, ethnic groups, interest groups, people who work or live together for a long time and have moral relationship. This presents a tension between ‘face-to-face’ society and abstract national society, where face-to-face societies have more permeable boundaries than state, and the state may be perceived as oppressive, corrupt, or remote.

a) Henry Maine (1861):

i) Status societies. Persons have fixed relationships to each other, based on birth, background, rank and position.

ii) Contract societies. Voluntary agreements between individuals, status based on personal achievement. Perceived as more complex than status societies.

b) Ferdinand Tönnies (1887):

i) Gemeinschaft (community). People belong to group with shared experiences and traditional obligations.

ii) Gesellschaft (society). Large-scale society. Driven by utilitarian logic, where the role of family and local community has been taken over by state and other powerful institutions.

These simple dichotomies are no longer followed by anthropologists as distinct boundaries within society are mutable. Power within a state may reside in political elite, but in ethnically plural states, the ethnic leadership may hold sway, or in poorly integrated states, local and kinship grouping may hold greater power than state politicians.

When setting out a study subject, anthropologists describe the scale of the subject (e.g. web use among teenagers in urban Europe).

4) Theories of culture

Possibly the most complex area in anthropology. The classic concept of culture is based on cultural relativism, which has been discredited due to its use to promote particular group claims, discriminate against minorities and promote aggressive nationalism. The key intellectual architect of apartheid was anthropologist, Werner Eiselen (Bantu Education Act, 1953).

a) No definition that all anthropologists agree on. A L Kroeber and Clyde Kluckholn (1952) – Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions describes and analyses 162 different definitions of culture.

The concept of ‘multicultural society’ indicates that culture has a different meaning to society – although there are similarities between them and are often used as synonyms for each other.

b) E B Tylor (1871). ‘Culture in its widest ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, customs, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society’.

c) Clifford Geertz (1960s). Interpretive Anthropology – shared meanings through public communications.

d) Objections to concept of culture:

i) Culture as plural can be seen as something that divides humanity, as the attention shifts from uniqueness of humanity to the differences between groups. (Boas – cultural relativism, Malinowski – field methodology, focus on single societies). Expressions of culture are unique and variable – but refer to universal, shared humanity.

ii) Problem of boundaries, internal variation and change. Delineating culture is problematic as there is considerable variation – often more so within groups than between groups.

iii) Mixed cultural forms and transnational flows of culture makes it more difficult to draw boundaries between cultures. Ulf Hannerz (1992) describes culture as flowing, dynamic process rather than static entity – culture as a global web of networks with no absolute boundaries, with nodes of varying density which are more or less stable.

iv) Inaccurate and vague nature of culture. Term used glibly to mean many different things and gives the illusion of insight. To understand what goes on in the world a more nuanced, specific concept is required.

5) Problems of translation

This includes translation of acts as well as language, and is mediated by necessary forms of compression and editing, which implies subjectivity. To understand a group it is not sufficient to simply observe, the anthropologist must learn the meaning and connotations of actions and words. Understanding only comes when a phenomenon is understood and explained in terms of its full meaning and significance to the group under observation – and how it forms part of a continuous whole. The main difficulty comes in translating abstract terms.

Problems: Misrepresentation, inevitable subjectivity of researcher, standard data organisation (gender, class, ethnicity) may not correspond to life-world of observed group.

Criteria for distinguishing good from bad subjectivity:

a) High level of detail.

b) Degree of context provided.

c) Triangulation with related studies.

d) Closeness of researcher to group (e.g. homeblindness).

6) Comparison

A means to clarify the significance of findings through contrasts that reveal similarities with other societies and build on theoretical generalisations. The aim of comparison is to understand the differences as well as the similarities.

a) Translation is a form of comparison – the native language is compared to the anthropologists own.

b) Establish contrasts and similarities between groups.

c) To investigate the possible existence of human universals (e.g. shared concepts of colour) – or to disprove them (e.g male aggression).

d) Quasi-experiment – anthropologists are unable to carry out blind studies, as the results would be inauthentic. Comparisons between two or several societies with many similarities, but with clear differences can provide an understanding of these differences.

7) Holism and context

Within anthropology holism refers to how phenomena are connected to each other and institutions to create an integrated whole, not necessarily of any lasting or permanent nature. It entails identification of internal connections in a system of interaction and communication.

a) Edmund Leach (1954) shows that societies are not in integrated equilibrium, but are unstable and changeable.

b) Fredrik Barth (1960s) transactionalism – a model of analysis which puts the individual at the centre and does not assume that social integration is a necessary outcome of interaction.

Holism has fallen from favour recently as anthropologists now understand that they are studying fragmented groups that are only loosely connected. However contextualisation may have become the key methodology; that is, every phenomenon must be understood within its dynamic relationship with other phenomena. The wider context is key to understanding single phenomena. For example – an anthropologist studying the Internet will explore both the online and offline lives of individuals. The choice of relevant contexts depends on the priorities of the researchers.

Disorganisation, and a surprising amount of useful information no comments

Having had time to look in to the two subjects (Geography and Biology) which I’m applying to user interface (UI) design, I’ve found a surprisingly large amount of topics, methods and skill sets within them which could be used by geographers and biologists to help answer my question. My next task will be to sort through all of them and reject the weaker arguments and develop the stronger ones, this could take a while…

Below, for those interested, are my brief (and badly written) notes on each and how they could apply, along with the textbooks I used (which, conversely, are very well written):

Geography – most information from these notes has come from “Practising Human Geography” (Cloke, Cook, Crang, Goodwin, Painter and Philo) and “Earth’s Climate, Past and Future” (Ruddiman)

Sifting, sorting and simplifying data – geographers use large data sets which often contain lots of anomalous and irrelevant data, drawing out the most important elements of something is a key skill which could be transposed in to producing a simple and easy to use UI.

Studies and public surveys – part of human geography includes sampling public opinion, while other geographers often examine physical structures (manmade and natural). Both of these produce useful data and are similar to user studies which are a key part of user centred design (UCD).

Set theory and grouping items – grouping relevant items together and finding links between different things would help to make a well laid out UI.

Quantitative and qualitative methods – when analysing data collected from studies these are useful skills for extracting meaning.

Statistical approach with inference – more methods for discerning information from data which are transferrable.

Awareness of the limitations of measurements – e.g. Children are measured as belonging to a household, when in reality they may move between two – this is a useful part of UCD which is often overlooked (in my experience). Many user studies do not properly analyse the limitations of their measurement techniques.

Town planning – the layout of a town is not dissimilar to the layout of items on a screen, both must take in to account the different types of people using them, as well as the underlying restrictions of the system they are built upon.

Cartography – refining very complex data in to simple form which is usable by almost everyone is an important goal for UI design, and one which cartography has mostly solved for it’s own data sets. Applying similar refinement techniques to other data sets could yield similar results. Cartography also has to consider the audience and the abilities of the users, which is a core principle of UCD.

Transportation geography – underground railway maps are a simple example of where this has produced a very usable interface by creating a vastly simplified and more readable version of the actual data, without loss of any of the relevant data (intersections between lines, etc.). A map of the actual paths of the London Underground lines is barely visible due to the scale that has to be used, but the version shown to the public is accessible to everyone, and even takes in to account disabled users.

Geology – layers in rock which contain different information could be (very tenuously) linked to layers of a UI containing different data. Although the metaphor breaks down, the mental model could be useful.

Cultural and socio-economic differences/demographics – accessibility if computer interfaces is very important, and geographers are familiar with analysing and segmenting people in to different groups which could be used to provide different experiences and interface types when using a computer program.

Observation of the world and people – this is an important part of UCD and geography

Breaking down objects in to functions – e.g. a city as a transport hub – computer programs can be seen as a collection of functions working together, which is similar to a city. This type of understanding is the opposite side of UI design to the user side, but equally important to make it functional and efficient as well as easy to use.

Climate – patterns on a small scale can be applied to large scale problems. This doesn’t always hold true, but it is usually a good idea to attempt to try/extend existing solutions before reinventing everything from scratch.

Weather – inference of future trends based on current and past patterns/data. Looking at how people have behaved before with other programs, and how designers/developers have done things before is important to learn what works and what doesn’t.

Erosion and removal of soft rock, leaving structural/important rock in place – the metaphor here could be used to remove excess and wasteful parts of the UI, leaving just the parts which are important

Ethical considerations – part of any user study is deciding what is acceptable and reasonable to do.

Systems theory – the interaction between different systems and parts of a system – this is used heavily in geography and applies to lots of areas

Biology – based on notes from “Campbell Biology” (Reece, Urry, Cain, Wasserman, Minorsky and Jackson)

Cell theory – cells are the building blocks of all life – building a UI could be analogous to building an organism, the whole is made up of lots of parts, each part has a function and each part is made up of smaller parts, then all of it has to work together.

Evolution and natural selection – applying these to UI design could see several possible designs being tested then the best parts of each combined to a new generation which is then tested again, until the best survives. Natural selection also suggests that the surviver will be the one which best suits the environment it is tested in, so there would be a possibility to produce several final versions for different users and scenarios.

Mutation – taking a working UI and changing parts of it could be used to avoid the local maxima problem.

Genetics – a core set of instructions/features – a program has a set of requirements which it exists to complete, these could be seen as the core genes of it which determine to a certain extent what it will have to look like.

Link between an environment and life that exists there – different experiences may be required in different places, for example on a train people behave differently to when they are at home in the living room, even though they are probably sitting down looking at a screen in both.

Emergent properties – the arrangement of smaller parts affects the properties of the larger object – the functionality of the whole has the ability to be more than the sum of the functions of the parts

Component parts – the view that something is built up from smaller sections into a whole

Properties of life:

Order – organisation of items in the UI

Evolutionary adaptation – a UI must change as the users’ needs change

Regulation – the flow of data which is displayed has to be managed

Response to the environment – a UI must change if the user changes environment or it is used by a different user in a new environment

Reproduction – this probably doesn’t apply…

Growth and development – users may have new requirements over time, or it may be necessary to create a basic version to start with and build on it for new releases

Energy processing – efficiency is important

Gossip, Graphs and Guerrilla Marketing no comments

Why would Web Scientists be interested in Gossip?

Gossip is defined as “idle talk; trifling or groundless rumour” between people and is usually thought of as being rather innocuous and of little consequence (OED 2013). The Web facilitates the free exchange of information regardless of quality or authenticity and this could be useful or contentious when mining the Web for data.

Gossip is a form of information exchange but unlike scholarly communication or financial transactions it is rarely coherent, uniform or predictable. The prolific use of the Web 2.0 in particular the social networking sites and micro-blogs allows gossip to spread between platforms and in different forms. A mosaic of verbal and pictorial information and more importantly combinations of the two spread throughout the Web.

Ultimately, gossip is a way of exchanging information in an informal and relaxed manner. Before Web scientists attempt to design or engineer new web technologies they must understand what the Web is being used for currently. This is of great use to Web scientists because it can help them understand how information can be exchanged faster and easier and how their efforts can facilitate this exchange.

The reader may feel that this review is nothing but mere folly and they could be forgiven for thinking that. However, the author would ask them to consider how the principles of gossip could be applied to more serious and practical fields e.g. disaster relief, management, law enforcement. Gossip transcends technical and social boundaries and so it will be of use when studying the Web as a socio-technical object.

Why Network Science?

Network science offers a near perfect set of techniques and practices for studying the Web. Due to the mixed lineage of this field it offers a variety perspectives of networks as social and technical entities. Biological networks are of interest as well – the study of other species such as cephlapods or bees could inform Web science about information exchange.

Network science leans upon sub-fields that have themselves been created from interactions by other disciplines e.g. graph theory (mathematics, computer science) and social network analysis (sociology and anthropology). This chimera of a discipline allows for the topic to be fully opened up and examined thoroughly by illustrating its interconnected nature.

Newman, Barabasi and Watts (2006:4) provide clear cut guidance as to why their discipline is different.

- It is focused on “real-world problems” and is willing to sacrifice theoretical purity for real world application.

- It views networks as dynamic entities and will not settle for static models.

- It aims to “understand the framework on which distributed dynamical systems are built”.

- It explains rather than describes networks and uses stochastic processes to understand the changes in networks.

It will provide a stimulating read to say the least and offers insights previously hidden in the fragments of other disciplines.

Why Marketing?

“The aim of marketing is to make selling unnecessary” Drucker (2001:20).

If gossip is the idle talk amongst people, marketing is the attempt to infiltrate this “idle talk” and make it into a profitable opportunity. Marketing provides a perspective borne out of commerce and academia and offers insight into how information exchange is made into a commercial product.

Marketing is made up of segments and channels. The segments are different markets and the potential consumers within them. The channels are the method by which a marketer will reach them and build a relationship with so as to continually acquire their custom. From humble posters in shop windows to multi-millionaire pound advertising campaigns, marketing is essentially about raising awareness through word of mouth. Marketers make use of traditional (offline) and digital methods and this means that the Web is of great importance to them.

Marketing provides a mixture of theatre and statistics. It has an array of metrics to measure the success of a commercial activity which can give marketing near-science like properties. It is heavily influenced by economics, business studies, psychology and computer science. Especially the statistical techniques and numeric concepts within these disciplines and how they can aid decision making. However, it also attempts to allure customers not through technical or economic measures but through appealing to consumer’s subconscious desires. For a campaign to be successful it must use art and design, music and even activism.

It will provide an opportunity to see how the Web is used to generate custom and subsequent profits. This demonstrates that gossip is used not just as a social mechanism but also as a commercial one.

Convergence of the two disciplines?

The emphasis on analysing social networks is an obvious property of both disciplines. It is not clear as to whether marketers have the capital (human, cultural, financial, physical) to utilise the same tools as network scientists. It may be the case that they can collaborate and share access to data and any insights gleaned from it. The interest in real-world social networks and observing them in real time is something that will be of use to Web scientists and will further extend their influence to other small-world networks.

P.S. This post was originally posted on 15/10/2013 – however, it failed to publish and only showed the title. The author apologises unreservedly for any technical blunders on their part.

Psychology in a nutshell no comments

This week I have been looking at the basics of psychology. After I talked to a friend in the Netherlands, who studies psychology, I came to the conclusion that the book ‘Psychology’ by Peter Gray would be a solid introduction to the discipline and could introduce me in an appropriate matter to the subject. I scanned over the 654 pages of the book and learned about psychology’s basic methodologies and research fields.

On the first page of his book, Gray states the following:

“Psychology is the science of behavior and the mind. In this definition behavior refers to the observable actions of a person or an animal. Mind refers to an individual’s sensations, perceptions, memories, thoughts, dreams, motives, emotional feelings, and other subjective experiences.”

(Gray, 2007: p. 1)

After this formal definition, Gray continues with explaining that there are three foundation ideas for psychology. The first idea is that behavior and mental experience have physical causes, the second that mind and behavior are shaped by experience, and the last is that the machinery of behavior and mind have evolved through natural selection (Gray, 2007: p. 2).

These foundational ideas are explored by using different research strategies. Gray recognizes three categories in which these strategies can be ordered. The first is research design, wherefore experiments, correlational studies, and descriptive studies are needed. The setting is the second category. Herewith, one must think of either field or laboratory research. Finally, the data-collection method is important. The basic types are self-report and observation (Gray, 2007: p. 29). Another important factor of psychology is the usage of statistical methods to understand the data that has been collected. According to Gray, descriptive statistics are used to summarize sets of data. Inferential statistics help researchers in their confidence about the collected data (Gray, 2007: p. 35).

After the basic methodologies of psychology, Gray goes into more detail and talks about the different fields that are being explored in psychology and have shaped it to what it is now. Human behavior is an important field, that is often being examined through genetic evolution and the environment around a human being (Gray, 2007: p. 49). Furthermore, cognition and neuroscience are important in studying the shaping of behavior and the mind.

An interesting example in which the field of psychology is particularly relevant to Web Science and the subject that I chose, online surveillance, is through laws of behavior as social facilitation and social interference. These terms are being described by Gray as influential on human behavior, because the individual knows when it is being observed and its behavior is being affected by it (Gray, 2007: p. 502).

This week I wrote on the basic definition of psychology and some of its methodologies. Next week I want to explore in detail which different fields of psychology exist and how they might relate to online surveillance.

Source

Gray, Peter. Psychology. Fifth Edition. New York: Worth Publishers, 2007.

How is gender equality represented on the web? Philosophy: back to basics. no comments

This post will cover defining equality and looking at some of the arguments against equality.

In order to look at gender equality at all, let alone on the web in relation to philosophy, the first logical step is to go back to the very basic philosophical question of ‘what is equality?’. The idea of treating all human beings as equals originated thousands of years ago, and with that age old ideology comes differing views and definitions of equality itself. Philosophy commonly defines four different types of equality: moral/ontological, legal, political and social.

Moral/Ontological Equality: This type of equality has been defined in several ways, but all to the same end. One definition is “the fundamental equality of persons” which takes the religious view that all are equal under God. Others have a less theological take but still denote that all human beings should be valued the same, without preferential treatment irrespective of the situation. For example, the ‘all women and children out first (or debatably all wealthy women and children out first) principle’ used on the titanic, would not hold true.

Legal Equality: Otherwise known as ‘equality of result and outcome’; this advocates that all people should be treated the same with respect to the laws they have to follow, and subsequent retribution if they fail to do so. Historically in America, black Americans had a substantially higher chance of receiving a conviction or a harsher punishment than a white American; in a truly legally equal society, all citizens would be tried against the same standards, without taking race, gender, religion or any other factor into consideration.

Political Equality: This equalitarian stance otherwise known as is based on all members of a political community should have an equal say when it comes to making laws or voting in public elections. Therefore no country where anyone who is considered a ‘lesser citizen’ and therefore not allowed to vote (e.g women up until the 20th Century, or the working class until the 19th Century) could claim to be ‘politically equal’.

Social Equality: This is the idea that all members of a society should have equal access to it’s resources and equally benefit from it. The fact that realistically (certainly for Britain) more money can buy you better health care, debatably better education with access to private schools, and the fact that our country still arguably holds class divisions means that we do not enjoy social equality. Unfortunately even countries/governments that have attempted to use communism (a socialist movement to create a classless society) still suffered from corruption and attempts to un-equalise the balance.

After defining these different types of equality, would it then logically hold that ‘gender equality’ would be where both genders can enjoy all four types of equality with no differentiation between them; which would also mean that in terms of how both genders are represented on the web, the way they are viewed, their legal and political rights in relation to the web, and the resources they are allowed access to on the web, should be exactly the same for both?

There are many arguments against these definitions of equality, that therefore would potentially invalidate the question above, as those characteristics of equality would no longer hold true.

The first argument against equality is that different elements of equality aren’t compatible; society is not by design equal. Even if it were possible to conceive a true ‘classless’ society, jobs/salaries/positions within society would still be different, and therefore ‘unequal’; and why shouldn’t they be? If one position requires a higher skill level than another, why shouldn’t the most skilled person for the job secure it? This then poses the question ‘should everyone be afforded equal opportunities, or just the ability to gain the skills to gain access to those opportunities in the first place?’. In relation to gender equality therefore, shouldn’t women and men be given the same starting blocks, with the capacity to make of it what they will. One gender shouldn’t be automatically considered over the other for any position, it should be based on skill, but both genders should have the abilities to gain those skills. To look at this matter in relation to gender representation on the web, it would logically follow that both genders should have the ability to hold any position socially on the web (e.g both should be able to contribute to academic resources) and they should be judged on merit and knowledge not gender.

The second argument is that it is impossible to adhere to full social equality. To enforce such strict rules would be tantamount to introducing a totalitarian rule over society. It has also been argued that a totalitarian esque rule doesn’t work as human nature means that society will always eventually rebel against such a strict rule; rendering utter equality infeasible. It would therefore be almost as impossible to ensure utter gender equality on the web. It would still be marginally easier than ensuring it completely within society (as unless we drift into the fictional realms of totalitarian novels such as 1984; the government has yet to work out how to read or control our thoughts) as all web traffic and content can be monitored, but it would still be a monumental task.

The third argument is that radical steps towards equality aren’t necessarily desirable. At what point would we be compromising our personal liberty in favour of forced equality? This resonates with the popularly quoted concern ‘political correctness gone mad’. Has the desire to treat everyone equally, and not cause offence irrespective of gender, race, religion etc gone too far? At what point would say a gender inequality based joke or phrase e.g ‘get back in the kitchen’ be considered a point of humour between friends, and at what point would it be regarded as blatant sexism and an example of gender equality?

My essay will address equality in it’s origins looking at all of these different types, in addition to the arguments against them to study how one would go about ascertaining the representation of gender equality on the web from a philosophical standpoint.

[1] D. Johnston “Plato, ‘Democracy and Equality'” in Equality, Indianapolis, USA: Hacket Publishing Company Inc, 2000, ch. 1, pp. 1-9.

[2] B. S. Turner “Types of Equality” in Equality, student ed. New York, USA: Tavistock Publications Limited, 1986, ch. 2, pp. 34-56.

Stuxnet and the Weaponisation of Malware no comments

In June 2010 the US and Israel are alleged to have attacked Iranian nuclear facilities. This assault was not carried out by an aerial bombing raid or any conventional military action. Instead, a number of devices at several sites which had been infected with a worm called ‘Stuxnet’ began faking industrial process control signals. This led to centrifuges used in the uranium enrichment process spinning several times faster than their mechanical tolerances would allow. Many centrifuges were destroyed and the enrichment process was severely disrupted.

This malware is the first example of nation states relying exclusively on malicious software to further a major foreign policy aim. It marks the introduction of a new form of warfare between countries, one which is perhaps more dangerous than any other kind, as unlike conventional conflicts, potent weapons become available to non-combatants and can be analysed, adapted and redeployed. Stuxnet spread beyond the Iranian industrial centres it was designed to attack (it is believed that a technician took an infected device, a laptop or possibly a memory stick, home and connected Stuxnet to the Internet). From there it infected hundreds of thousands of computers around the world and was even traded on the black market. In fact two of the most sophisticated pieces of malware of the last 2 years (Duqu and Flame) are considered to be expansions of Stuxnet.

However, this new kind of warfare is also depressingly similar to older forms – it led to retaliatory cyber-attacks on American and Israeli institutions by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, there was an exchange of propaganda as America and Israel denied all knowledge of Stuxnet while the Iranians sought to underplay its effectiveness and there was an increase in the determination and belligerence of all participants – analysis has shown that Iranian uranium enrichment actually increased in 2010, and the assassination of Iranian scientists involved in the programme began in earnest.

Disciplines:

1. Historical

I want to try and place Stuxnet in some kind of historical context. Was it really the first time a nation had attacked another nation with malware for foreign policy purposes? What are the parallels with previous arms races? Can previous conflicts (cyber and conventional) give us guidance on how this new kind of warfare is likely to develop?

2. Ethical/philosophical

Is electronic warfare ‘preferable’ to conventional warfare? No lives were lost (that we know of) through the use of Stuxnet, whereas a conventional US/Israeli attack on Iran would certainly have escalated and led to significant loss of life. Is this a new ‘clean’ kind of warfare? Will it reflect the post-war arms race and the concept of a nuclear deterrent? Will there one day be malware so dangerous it will force an uneasy peace?