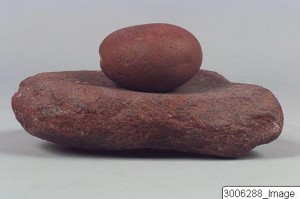

Saddle Quern

Bread is perhaps the ultimate convenience food: a ready-prepared meal that can be carried on the person and eaten as hunger dictates without further preparation. Yet bread is not a self-evident food-stuff, as it is made from flour, and this requires a mill or quern to make it. In its simplest form, the saddle quern, two stones rubbing together, becomes a vital instrument supporting life. There are many varieties of saddle quern which tell the story of our growing involvement with grain and flour. As long as 33,000 years ago, in the Palaeolithic, humans began to grind the seeds of wild grasses in ‘dished querns’ which persisted through the Mesolithic into the Neolithic of Britain. However, in the Near East a new type of milling device, the’ long quern’, was being developed, capable of grinding more grain much more efficiently. It was introduced into Central Europe by the Linearbandkeramik culture but did not reach Britain until the late Bronze Age. Its use implies that flour and hence bread were gradually becoming more important in the pre-historic diet.

Reading

Takaoğlu, T. 2005.Coşkuntepe: An Early Neolithic Quern Production Site in NW Turkey, Journal of Field Archaeology 30, No. 4: 419-433

Williams, D.F. and Peacock, D. (eds.) 2011. Bread for the people: the archaeology of mills and milling, Oxford: Archaeopress (University of Southampton Series in Archaeology, No.3.)