Andrea Franceschin

Zimbabwe is a country so rich that ancient legends say that God itself was ashamed of it as He gave too much to a single place of his Creation.

I spent a fantastic 10 weeks in the Republic of Zimbabwe collecting data for my MRes research project. I was based at Dambari Field Station, the headquarters for the Dambari Wildlife Trust, which is situated 25 kilometres from Bulawayo, the second biggest city in Zimbabwe. On arrival, I finally had the pleasure of meeting my Marwell Wildlife supervisor, Dr Nicola Pegg, and my field assistant, Tafadzwa. The three of us then spent 10 days together finalising our plan for data collection, which was to take place in the Matopos National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site situated more than 50 kilometres away from our base camp.

The idea behind my MRes project is to look at the differences of relative species abundances of main herbivores in relation to human impacts on the area. I primarily looked at the impact of fire and livestock and plan to investigate whether these could be used as a management tool.

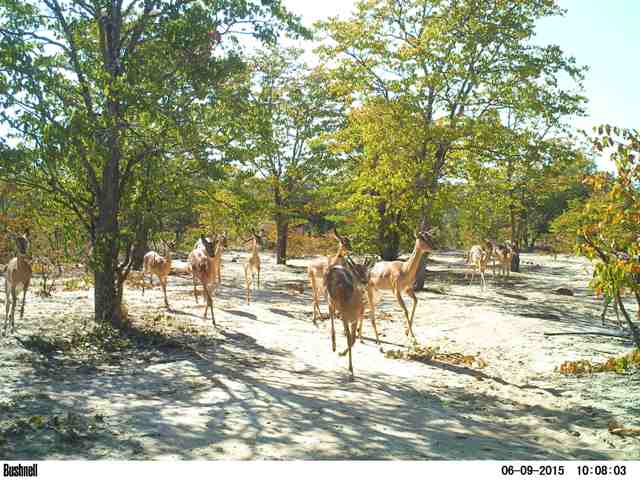

Tafadzwa and I, along with Faisal, another student from the MRes, spent 8 weeks in the field collecting our data, returning to base camp only during the weekends. Spending so much time out in the park gave us a fantastic opportunity to witness (with our own eyes or with our camera traps) the majesty of some of the park’s top species, including white rhino Ceratotherium simum, leopard Panthera pardus pardus, hyena Crocuta crocuta and impala Aepyceros melampus.

We employed two different methodologies for the data collection, camera traps and line transects (some of our camera trap images can be seen above). Along our 300m line-transects, located in various areas of the park, we recorded dung piles and spoor (mainly footprints). Zimbabwe, and over all of the Matobo Hills, the environment can change incredibly quickly: you can start your 300 meters in grassland and finish in very dense bush, crossing a muddy reedbed in the middle! Sometimes it was not even possible to follow a straight line, due to the thick spiny shrubs, the scratches and insect bites though definitely bear witness to a good job done! One day, when we were starting our transect assessment, we had an incredible and exciting face-to-face with the big guy of Matopos, the white rhino. These kinds of encounters are not uncommon in the park and they can happen at any time, but as the largest of the grazers, these animals must be treated with caution and respect. It still amazes me that an animal of such a size can approach without making single sound!

During the last week, after some rough data analysis and sorting of images (some of the cameras had more than 10000 pictures, sometimes the majority of which were just moving grass!), I got the chance to relax a bit and spent a couple of days at the Mosi-oa-Tunya (The smoke that thunders), also known as Victoria Falls, situated on the border with Zambia.

- Tafadzwa, Faisal and I measuring a line transect

- ‘The smoke that thunders’ – Victoria Falls

Back in the UK at the beginning of July, the second part of the work began: the statistical analysis and the write up. This was not as much fun as the data collection but still a crucial component of the project!

Once back, I also received some very nice news that really made me proud: one of my pictures shot in Kenya during the MRes Wildlife Conservation fieldtrip last November (see related blog post if you are interested) was chosen to be on the front cover of the University of Southampton Postgraduate Symposium booklet. It was just a shame that I hadn’t been around at the time to take part in the symposium itself.

Concluding this short snapshot of my experience, I hope you can begin to imagine the richness of Zimbabwe: a country full of incredible wildlife, with few fences or borders; breathtaking landscapes; friendly people, as far as I can tell from my experience working closely with the Park Rangers (who I thank for their precious help); and monumental rocky formations.

Posted By : dvf1e13