The title of the book was decided late on. ‘Slavery and Revolution’ was my working title throughout the writing process. But with the manuscript completed, the press wanted a change, and we eventually agreed on White Fury: A Jamaican Slaveholder and the Age of Revolution. The book, as the title makes clear, is about a slaveholder. But it also about more than that—it seeks to examine British slavery and the late eighteenth-century revolutions that undermined it. Still, it is Simon Taylor, the richest colonial slaveholder of his generation and a prolific letter-writer, who remains the main point of focus. In fact, a big part of what I wanted to achieve was to explain how a man like Taylor was able to perpetuate the world of Caribbean slavery, and how he came to defend it—right down to the last weak scratchings of his pen. Here, I reflect on why White Fury is an appropriate title for a history book about this man, and I add a few thoughts about why I think understanding Taylor’s white fury matters to us in the present.

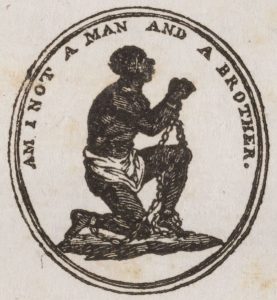

‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’, abolitionist slogan and emblem, c.1788.

By the year 1807, Simon Taylor’s anger was running hot. This old white slaveholder was, by then, approaching seventy, and the abolitionist campaign, which he had vehemently opposed since it first began two decades earlier, was on the brink of a major success. After many years of debate, the imperial parliament in London was poised to put an end to the transatlantic slave trade. It pitched Taylor into a state of incandescent fury.

‘Am I not a man and a brother?’ was the slogan of the abolition movement, always accompanied by the image of a kneeling African, begging for help—a message that grabbed imaginations and changed perceptions. And, for a man like Taylor, whose wealth was based on buying, selling, and exploiting enslaved Africans, it was nothing less than a disaster. From his home in the British colony of Jamaica, he had long raged against abolitionists. To him the figurehead of the anti-slave-trade campaign, William Wilberforce, was a ‘hell-begotten imp’, spreading ‘infernal nonsense’. Taylor continually expressed outrage that such a man had misguidedly taken up the interests of ‘negroes’ against those of white colonial slaveholders. Taylor had never been able to understand Wilberforce.

Taylor’s view of empire was built around the principles of white supremacy and white solidarity. To men like him, the only people who could be considered ‘natural born subjects’ of the British Empire, and therefore deserving of its care and protection, were whites; and he considered black people merely as items of property. He struggled to understand how any truly patriotic Briton could see things differently. How could the British public and parliament fail to see that colonial slaveholders were the most precious and useful inhabitants of the empire? How could they prioritise the welfare of black slaves over the interests of their fellow white Britons?

Taylor was born in Jamaica in 1740, into a family of slaveholders and into an empire that seemed to belong to such people. The eldest son of a Kingston merchant, he was packed off to school at Eton before returning to Jamaica in 1760, taking over the family firm, and branching out into the sugar business. He was investing in the most lucrative and dynamic part of the eighteenth-century British imperial economy. Sugar planters were notoriously wealthy, Caribbean sugar was Britain’s most valuable overseas import, and the enslaved Africans whose labour made all of this possible were treated as a disposable resource. Taylor bought and developed three huge plantations—which, like all British sugar estates, were worked by hundreds of enslaved workers, imported to the Caribbean colonies from West Africa via the transatlantic slave trade. He was poised to become one of the richest British sugar planters of his age. He had the world at his feet.

And Taylor prospered, and his influence grew. He was middle-aged by the time that the abolition movement emerged. At first, he saw it as a naïve and sentimental outpouring of emotion that would soon wither, once sensible men of business exposed its absurdity. But by the time he entered his sixties, abolitionism (coupled with revolutionary uprisings by enslaved people throughout the Caribbean) had forced him to accept that the world of plantation slavery that he had worked all his life to sustain was more vulnerable than at any time he could remember. ‘I am glad I am an old man’, he grumbled in a letter to an old friend, as the eighteenth century gave way to the nineteenth, and confessed he was ‘really sick both in mind & body at scenes I foresee’.

A few years after, on receiving the long-anticipated news that parliament had reached its momentous decision to put an end the slave trade, his reaction was predictable. He felt ‘really crazy’—‘lost in astonishment and amazement at the phrensy which has seized the British nation’. Of course, parliament had only abolished the trade in slaves across the Atlantic. (By the time concrete plans were laid to end slavery itself, Taylor had been dead for two decades.) But the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 was, nonetheless, a major political setback for Taylor that dealt a significant blow the wider system of slavery. It might be tempting, then, to view Taylor’s rage as the behaviour of a man failing to come to terms with inevitable, irreversible defeat. Perhaps, we should try to take comfort in the knowledge that Taylor and the world of slavery that he built with such self-confident conviction and defended with such venom are now safely in the past. That, however, would be unjustifiably complacent.

When we look at it carefully, we see that Taylor was angry not because he believed that defeat was certain but because he believed that it could, and should, be averted. And privileged, vocal, outraged men like him can be influential even when major decisions go against them. In the political wrangles over the dismantling of the British slave system, slaveholders won large concessions and retained significant privileges. What is more, the kind of angry reaction to change vocalised by a man like Taylor is not simply a thing of the past. Instead, Taylor’s fear and outrage are often chillingly recognisable. Again and again between his times and ours—through unfinished struggles over emancipation, decolonization, and civil rights—those who have grown up as beneficiaries of white privilege have responded to pressure for equality, increased diversity, and even the most basic of reforms, as though those were types of oppression. Institutionalised racism rooted in colonialism and slavery proves stubborn in the face of challenges, partly because when old white privileges are confronted, indignant white fury—of the sort that Taylor so luridly expressed—is rarely far behind.

Christer Petley

White Fury: A Jamaican Slaveholder and the Age of Revolution is published by Oxford University Press (£20, ISBN 9780198791638) click here to buy