Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Complexity and Psychology – can you have both? no comments

Hello all,

Apologies for my lack of blogging, I’ve been doing some reading over christmas (I trust everybody had a good christmas) and I wanted to share my thinking on the methodological approaches of both psychology and complexity. I think there is a fundemental issue here as to how we approach Webscience (are we going with Webscience, webscience Web Science or web science these days?) and the role of the different subject areas we’ve be learning about.

The traditional psychological approach shares much with the type of research we learn about in research methods. The positivist idea of isolating a variable and testing it either in the lab or via observation. Complexity differs as components (people, web pages) are affected by their interrelationships. So, isolating a particular part of the system for testing makes little sense as the effects of one variable in isolation say nothing about the collective effects.

If you watch the September Royal Society presentations, Nigel introduces webscience as a multidisciplinary area covering a whole range of subject from the structure of the web to humanities. In the complexity literature, however, there is a fundemental rejection of a positivist approach to dealing with complex systems. This is not to say there is no benefit to be gained, just that the two subject areas are tackling different questions;

Positivist experimentation – what happens at the interface between the web and the individual

Complexity – how does the network function as an entitiy in itself

So the question I have is what are we actually studying when we talk about webscience? Are we taking what we know of complex systems formation and then working out what effects that will have on people or, are we viewing people as part of the system in which case removing them to conduct experiments is impossible without altering the system.

My essay writing efforts have been along these lines – what are the methodological constraints of each approach and can they inform each other in a holistic explanation of the system…

Identity (Post 6 – Anthropology summary before moving on to Psychology) no comments

As I have spent the majority of my reading time so far on a single book, I have decided to extract and list the key points from my previous blog posts, and then cross-examine these with the content of Cultural Anthropology: A Contemporary Perspective by Keesing and Strathern. This should hopefully help to identify the most common areas which both books cover, and this in turn should indicate what the key fundamental areas of anthropology revolve around.

Topics blogged about previously:

- Ethnocentrism

- Cultural realism

- History:

- Diffusionism

- Globalisation

- Ethnography

- Emic and Etic

- The Social Person/Human Existence

- Statuses and Roles – Goffman

- The Self – Brian Morris (1994)

- Socialisation

- Anomie

- Social systems and social structures

- Habitus (Bourdieu)

The topics in bold are those I believe Keesing and Strathern cover to complement Hylland Eriksen. A couple of interesting points that I also noticed while skimming through Cultural Anthropology are that Anthropology is a lot less scientific than other social sciences – it is difficult to apply questionnaires, experiments etc when carrying out an anthropological study so research techniques have fallen back on how to “learn, understand and communicate”. Scientific method is often inappropriate – as there is “nothing to measure, count, or predict”.

This post was really just about summarising what I have covered in Anthropology so far, as I would now like to move on to Psychology having not touched it so far. I think a lot of the basic theories and ideas have strong links to sociology, but there is a definite cultural twist on them. I aim to cover the basic principles of psychology in the next couple of weeks, and then relate both disciplines to Identity once I have this understanding.

Cognitive Extension, part 3 no comments

It is (slowly) dawning on me as I look at some of the earlier hypertext systems, that some of them were, in some ways, all about cognitive extension. And when I say “earlier”, I mean those that have been tried out in the past, already. Namely, Memex and NoteCard. What I don’t mean is that NoteCard is an earlier version of the Web. If anything, it seems to be a second generation hypermedia system, while the Web (I’m starting to think) is a first generation system.

I’m thinking the Memex, for example, which was to support and supplement one’s memory, is a cognitive extension just as the notebook of the person with Alzheimer’s during his visit to the Museum (those who understand that reference, know what I’m talking about).

Similarly, the NoteCard computer environment wasn’t built to replace the intellectual creative process, but to support it. To help make sense of ideas, manage and present them.

So is the Web a tool a cognitive extension?

Autopoiesis & Network Science no comments

This weeks’ complexity lecture on network science covered much of the content from the Foundations lectures, and from the book Linked. This is something I find particularly interesting, and of relevance to collective problem solving, primarily in terms of characterising the structure of the networks people can form. Interestingly, human social networks are very different from most other networks because they are characterized by a positive rather than a negative node degree correlation.

Last week, the complexity lecture was on Autopoiesis – an attempt to create a non-circular definition of life. It defines it as a self-sustaining system with it’s own semi-permeable boundary to the outside world, containing various processes that both sustain themselves and maintain the membrane. This leads to the extraction of nourishment from the external environment and excretion of waste. Whilst this was designed primarily to clarify the distinction between life and non-life at the microscopic level, the analogy to human groups (such as, for instance, the Catholic Church) may be of some interest to my topic in terms of answering – what is it that makes a group (such as one formed online to solve a problem) sustainable?

Ecology no comments

For the past couple of weeks I have been reading about Ecology, primarily from “First Ecology” (Beeby, Brennan. 2ed 2004).

The book says that “Ecology is the science that seeks to describe and explain the relationship between living organisms and their environment” and the study of “the mechanisms by which species evolve, flourish and disappear.”

Interactions between species are an important aspect of ecology. Interactions are driven by the need for organisms to acquire resources, and could be co-operative, competitive or otherwise. Collaboration between people on the web could be seen as analogous to a co-operative ecological interaction.

Organisms need resources in order to survive; these resources might include water, food, sunlight (for organisms that photosynthesise) or simply space. Competition for resources is at the heart of evolution, since the organisms best suited to their environment (and hence best at harnessing the available resources) are more likely to survive. However, it is not enough for an organism simply to survive, in order to be truly successful it must pass its own genetic information on, through reproduction. We can, therefore, think of the protection and transmission of its own genetic information as being the “goal” of any given organism. Such transmission is itself a crucial part of the evolutionary process.

To achieve this goal, species have developed a huge range of strategies; from fast reproduction that can monopolise a resource, to complex colonies with thousands of individual organisms that share much of their genetic information, to highly-specialised inter-species dependencies, some of which are mutually beneficial and others which are parasitic.

Complexity is an inherent part of ecology. The environment and organisms that live in it are highly interconnected, which poses similar problems to those faced by sociology and web science (as previously discussed). I’ve started looking into how Ecology deals with this complexity, but that’s another post. I also want to look into symbiosis and other highly-cooperative interactions.

Blog post 6 – Classical Criminology no comments

This week I have carried on my reading of Roger Hopkins Burke (2005).

In my earlier blog I talked about the rational actor model, however central to this is the classical school of thought. Ideas of the classical school argued that people are ‘rational creatures’ who look for pleasure while at the same time trying to avoid pain. Therefore, any punishment that is inflicted must significantly outweigh any pleasure that one might have achieved as a result of a criminal act, in order to deter people from committing crimes. The classical school can be thought of as having a significant impact on the influence on the modern day justice system because of the notions of ‘due process’ (Packer, 1968) and ‘just deserts’ (von Hirscg, 1976).

There were two key classical school theorists – Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham.

Cesare Beccaria (1738-94)

Was the author of an influential book that had a huge impact on European and US legal thought. He disagreed with inconsistencies in the government and public affairs Beccaria suggested that criminals owed a ‘debt’ to society and that the punishment for criminals should be in proportion to the seriousness of the crime. He recommended that capital punishments was no use and instead imprisonment should be extended, with the conditions of prisons to be improved. However, it is his theory of criminal behaviour that has provided the grounding for the rational actor model, using the concepts of free will and hedonism. Beccaria proposed that human behaviour is based on the pleasure-pain principle, so any punishment should reflect that. Beccaria’s ideas have had a significant effect on the modern criminal justice system and the doctrine of ‘free will’ can be seen today in the majority of legal codes, with a major impact on popular ideas of justice.

Jeremy Bentham

He attributed criminal behaviour to their incorrect upbringing or socialisation instead of innate inclinations to offend. Bentham considered criminals as ‘persons of unsound mind’ who have no self discipline to manage their passions. His ideas are similar to that Beccaria suggesting that people are ‘rational creatures’ who try to avoid pain while looking for pleasure. Likewise, similar to that before, punishment must outweigh any pleasure that is gained as result of committing a criminal act. However the law must NOT decrease the ‘greatest happiness.’ Bentham also believed in ‘free will,’ with his work proposing that criminality might be ‘learned behaviour.’

The influence of the Classical School

According to Hopkins – Burke (2005) the classical school is considered influential in legal doctrine that emphasises conscious intent or choice, (e.g. mens rea or guilty mind), in sentencing principles (e.g. responsibility), and in the structure of punishment (e.g. sentencing tariff). Particular this school can be seen in the ‘just deserts’ approach to sentencing. This includes four key ideas according to von Hirsch (1976):

• Only an individual found guilty by a court can be punished for the crime

• Anyone that is found to be guilty of a crime must be punished

• Punishment must not be more than the nature of the offence and culpability of the offender

• Punishment must not be less than the nature of the offence and culpability of the criminal

All of these are founded on the notion first suggested by Beccaria and Bentham. There is importance on the idea s of free will, and rationality, proportionality and equality, with an added importance on criminal behaviour that looks at the crime and not the actual criminal, in relation to the pleasure-pain notion to make sure that justice is done by equal punishments for crimes of the same nature.

According to Packer (1968) the criminal justice system is said to be founded on the balance between due process and crime control. Due process stresses that it is the role of the criminal justice to prove that the defendant is guilty beyond all reasonable doubt, however the state has a duty to prove the guilt of the accused (King, 1981). This is based around the idea of innocent until proven guilty. This model requires the enforcement of rules that are concerned with powers that the police have and the use of evidence. This due process system recognises that some guilty people may get off scot free and remain unpunished. But this is considered to be acceptable if it means that innocent people are not wrongly convicted and punished. On the other hand, a high rate of aquittal gives the impression that the criminal justice system is inadequate and not performing their jobs properly, and therefore failing to deter criminals.

Contrastingly, a crime control model places emphasis on achieving results with priorities on catching, convicting, and punishing the criminal. In this model there is what’s known as a ‘presumption of guilty’ (King,1981) and there are less controls to protect the offender. It is seen as acceptable if some innocent individuals are found guilty. In this model it is the interests of the victims, and society that are given the biggest priority rather than the accused. Criminals are thought to be deterred due to the shift processing nature of the system, therefore if a person offends they are likely to be caught quickly and punished – therefore what’s the point?! The primary foundation of the crime control model is to ‘punish the guilty and deter criminals as a way of reducing crime and therefore creating a safer society,’ (Hopkins-Burke, 2005).

Psychology – The Biology of Behaviour no comments

This week I have continued my reading of Carlson et al. (2007) focusing on psychology, but particularly on the brain and its components, drugs and behaviour, and the controlling of behaviour and the body’s functions.

The brain and its components

The brain is the largest part of nervous system and contains 10billion -100billion nerve cells. All of the nerve cells are different sizes, shapes, functions they carry out and chemicals they produce. To understand the brain we need to look at the structure of the nervous system. The brain has 3 primary jobs: controlling behaviour, processing and storing information about the environment and adjusting the body’s physiological processes. There are two divisions which make up the central nervous system: the spinal cord and the brain. The spinal cord is connected to the base of the brain and runs along the spinal column. The brain contains three major parts:

The brain stem – controls physiological functions and automatic behaviours

The cerebellum – controls and coordinates movements

The cerebral hemispheres – concerned with perceptions, memories

The brain and spinal cord float in a liquid known as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that provides a cushion like protection. A blood brain barrier, ensures less substances pass from the blood to the brain to reduce toxic chemicals. A cerebral cortex, which is a 3mm layer of tissue, covers the surface of the cerebral hemisphere and has a billion nerve cells. The brain works with the body through the peripheral nervous system.

Sensory information, decision making, and controlling muscles, are all sent to the brain through neurons which make up the nervous system. To receive, process, and transmit information neurons contain; dendrites, soma, axon, and terminal buttons. Support is provided by glia, that also produces chemicals required by neurons, remove chemicals not required and help protect neurons from infections.

Neurons communicate with cells through synapse. When a message is sent from the presynaptic neuron it is received by the postsynaptic. A neuron accept s messages for lots of terminal buttons which results in terminal buttons creating synapses with several all neurons. Communication between synapses is chemical producing called neurotransmitter. When the axon is fires an actions moves down an axon causing the terminal buttons to release the neurotransmitter chemical.

Drugs and Behaviour

Chemicals that can be found in nature can affect people’s perceptions and behaviours. But some of these chemicals can be useful and are used as therapeutic remedies. By understanding how drugs affect the brain, help us to understand disorders and how to develop new methods of treatment.

Drugs can be said to alter our thoughts, the way we perceive things, the emotions we have, and the behaviour we demonstrate. This is achieved by affecting the activity of the neurons in our brain. Some drugs can stimulate or inhibit the release of neurotransmitters (chemical that is realised when neurons communicate) when the axon is firing, e.g. the venom of a black widow spider. Some drugs can stimulate (e.g. nicotine) or block postsynaptic receptors (e.g. cocaine). Finally, some drugs can impede on the reuptake of the neurotransmitter after it has been released, e.g. botulinum toxin or block receptors all together e.g. curare.

There are two important neurotransmitters that help achieve synaptic communication:

Glutamate – has excitatory efforts, every sensory organ passes messages to the brain through axons with terminals that release glutamate. One type of glutamate receptor – NMDA can be affected by alcohol. This why some ‘binge drinkers’ sometimes say they have no memory of what happened the night before when they were drunk. Likewise if a person has been addicted to alcohol for a long time this receptor can become suppressed, making it more sensitive to glutamate. So if a person stops drinking alcohol then this can strongly disrupt the balance of excitation and inhibition in the brain.

GABA – has inhibitory effects. Drugs that suppress behaviour, cause relaxation, sedation, and loss of consciousness act on a certain GABA receptor. For example if Barbiturates are taken in large quantities they can affect how a person walks, talking, cause unconsciousness, comas and even death.

Muscular movements are controlled by Acetylcholine (ACh) as well as controlling REM sleep (the part of sleep where most dreams occur), activation of neurons in the cerebral cortex and functions of the brain that are concerned with learning. ACh receptors are stimulated by the highly addicted drug nicotine. However the drug curare can block Ach receptors causing paralysis.

Dopamine is important in helping movement and helps in reinforcing behaviours. People with Parkinson’s disease are often given the drug L-DOPA to accelerate the production of dopamine. Drugs such as cocaine and amphetamine stop the uptake of dopamine and with people abusing these drugs would suggest that dopamine plays a role in enforcement.

Norepinephrine is said to increase vigilance and helps control REM sleep. Serotonin helps to control aggressive behaviour and risk taking, and drugs that have an impact on the uptake of serotonin are used to treat disorders concerned with anxiety, depression and obsessive compulsive disorders.

Control of behaviour and the body’s physiological functions

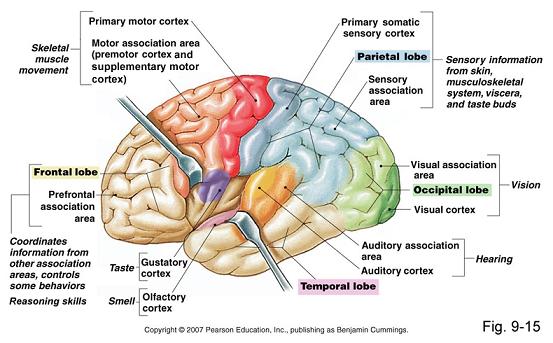

Figure 1. A side view of the brain illustrating the four lobes of the cerebral cortex, the primary sensory and motor areas and the areas of the association cortex

Figure 1 shows how the cerebral cortex part of the brain is split up into four parts also known as lobes – the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe and the occipital lobe. The areas of the cerebral cortex that receive information from the sensory organs are the primary visual cortex (concerned with visual information), the primary auditory cortex (concerned with auditory information), and the primary somatosensory cortex (concerned with information with regards to body senses).the area of the cerebral cortex concerned with the control fo movement is the primary motor cortex and the association cortex is concerned with learning, perceiving, remembering, planning and moving.

Some functions within the brain are lateralized both hemispheres are responsible for different functions. The left hemisphere takes part in analysis of information, and controls serial events (e.g. talking, understanding speed of other people, reading and writing). Whereas the right hemisphere is responsible for synthesis, puts separate elements together to create the bigger picture e.g. draw sketches, read maps. It is also involved in understanding the meanings of certain statements, and damage to this hemisphere can alter these abilities. Although they are responsible for different tasks, these hemispheres combine information through a bundle of axons connecting the two, known as the corpus callosum.

Behind the central fissure are lobers that are reponsisble for learning, perceving, and remembering:

Occipital lobe as well as lower lobes – information concerned with seeing/vision

Upper temporal lobe – information concerned with hearing/auditory

Parietal lobe – information concerned with movement/sensory

However these lobes also perform other functions such as processes concerned with perception and understanding of the body. the lobes situated at the front are responsible for motor movements, such as planning strategies for action. Similarly, the Broca’s area (left front of he cortex) is used to control speech.

Situated in the Cerebral hemispheres is the limbic system which is key when it comes to learning, memory and emotions. This is made up of lots of areas of the limbic cortex as well as the hippocampus and amydala, both of which can be found in the temporal lobe. The latter is concerned with emotions and such behaviour, e.g. aggression and the hippocampus takes part in learning and memory. People who damage the hippocampus are unable to learn anything new but can remember and recall past memories.

The brain stem is made up of three parts:

The Medulla – manages heart rate, blood pressure, rate of respiration

The Pons – manages sleep, and how awake someone is

The Midbrain – manages movements when fighting and when involved in sexual behaviour

Sensory information is received by the hypothalamus, this includes information about changes in the body’s physiological status, e.g. body temperature. It also manages the pituitary gland which is attached to the bottom of the hypothalamus. It also manages the endocrine system (endocrine glands).

Hormones are similar to neurotransmitters as there effects can be seen by stimulating receptors, but they work over a much larger distance. When these hormones combine with receptors they result in physiological reactions in the target cells (receptors in certain cells). The hypothalamus manages homoeostatic processes by its control of the pituitary gland and the autonomic nervous system. However, it can also cause neural circuits in the cerebral cortex to perform more complicated, learned behaviour.

My blog post on criminology will follow shortly

Figure 1 taken from http://samedical.blogspot.com/2010/08/nervous-system-cerebrum.html

Economic Fundament no comments

Having now covered the beginnings of Politics, I turn to Economics (with cyber-warfare ever in mind). To begin my studies in this subject I’m using the text book Foundations of Economics by Andrew Gillespie, which has so far been a reasonably pleasant, if not too challenging read. The book is split in to two sections – one on microeconomics (dealing with firms and individuals etc.) and the other macroeconomics (inflation, economic growth and international trade etc.) I suspect as I delve further into the subject I will focus more on macroeconomics as this is where the economics of warfare and international relationships come into play, and therefore may be the most effected by cyber-warfare. However before I can gain a proper understanding of this, I need to understand some economic fundamentals.

The first thing to understand is what is the problem that led to the birth of economics in the first place (what with economics being a man-made science). The main issue at the heart of economics is that we have infinite wants, but only finite resources with which to satisfy them. Therefore decisions have to be made (along with some sacrifices) and this applies to both individuals and, more conventionally, countries as a whole. Economies in general have 4 resources with which to work with…

1) Land: The physical land along with its minerals (for example oil or diamonds).

2) Labour: Number of people willing and able to work along with the skills they have. It is also important to consider here the value of knowledge and the effects of increasing it or sharing it.

3) Capital: Quantity and quality of capital equipment such as machinery and infrastructure.

4) Entrepreneurship: Ability of managers to think of new ideas and to take risks.

(With cyber-warfare in mind, 2 and 3 (and possibly 4) seem like the most important resources for this issue.)

Now we know what an economy has to work with, a number of decisions have to be made…

1) What is to be produced?

2) How to produce?

3) Who to produce for?

Naturally we can’t produce everything, in a manner that creates the best products all round and can be distributed to everyone. Therefore the problem of opportunity cost arises, that is to say what could be achieved in the next-best alternative? What do we forgo by acting in this way? Nevertheless these questions need answers and there are two diametrically opposed models for answering them: planned economies and the free market.

In a planned economy the government decides what goods and services should be produced, what combination of labour and capital should be used for any given industry and how the goods and services should be distributed. This however can lead to many inefficiencies, with the government not only having to gather lots of information as to what they need to do, but also actually going ahead and making the right decisions – they could easily produce the wrong quantity of a particular good or service. Similarly they have no pressure to run efficiently as the consumers of the goods and services have no alternative sources, which leads us on to free markets.

In the free market, the aforementioned questions are answered by the interactions of the market forces supply and demand. The government does not intervene and leaves decisions to be made by firms and individuals. If there is demand for a good and a firm can produce it, and still make profit, then it will go ahead and start producing. Only what is demanded gets produced due to a firm’s desire to make profit and there is an incentive to act efficiently as firms are competing against rivals, with all firms in the market wishing to maximise profits. However, this model also has its problems – mainly that a profit cannot be made from providing many goods and services and yet these goods and services may be required. Therefore the government may need to step in and provide certain essential public goods such as street lighting, or, more importantly, education or health services. On the other hand, the free market may find a profit in providing goods, undesired by society as a whole such as guns or illegal drugs.

Therefore in reality, economies are neither completely free market nor completely planned, they include elements of both. Bringing this make to cyber-warfare, one wonders under which category it may fall in the future. If a country wishes to carry out a cyber-based attack on another – does this fall within something the government provides as is the case with conventional armies, or it could it simply outsource the problem to a more efficient company with its own private ‘cyber-army’? Also, to bring this down from an international level, could cyber-warfare play a part in industrial espionage/sabotage? A powerful company in one market, may be able to stop smaller companies entering the market using a cyber-attack or harm its rivals already in the market. With cyber-warfare being so unlike traditional warfare in that it is much cheaper and less violent, companies could quite easily partake.

Back to Economics, another concept that is heavily drawn upon is that or marginal cost/benefit. This concept rather simplifies the process of making decisions: if the marginal cost of something is greater than the marginal benefit then don’t do it (although I suppose the problem lies in measuring the cost and benefit and trying to determine which is greater). This type of thinking may be taken into account when considering cyber-warfare however, with the marginal cost of cyber-warfare being much less than that of conventional forces – is the marginal benefit just as good however (e.g. key infrastructure could be taken out using either cyber or conventional means). Also if the marginal cost of warfare is much greater than the marginal benefit, this does not mean the warfare has to stop altogether, the costs could simply be rearranged so that it is at least equal to the benefit – cyber warfare may be a means to achieve this. (I feel I should point out at this point, I am not an advocate for warfare, but I am trying to see the situation from a warring economy’s point of view. In most situations the best way of reducing the cost of the war would be to end it!)

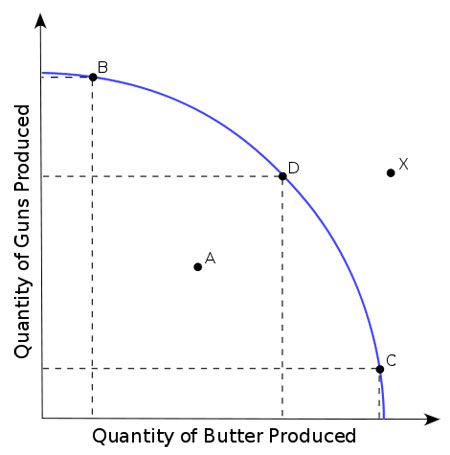

The final concept covered by my readings thus far is that of the production possibility frontier (PPF), a graph which shows rates of production for two different goods or services and how overall production changes when resources are shifted from the production of one to another. An example of a PPF is shown below (image taken from Wikipedia):

All points on the curve can be described as productively efficient. When the quantity of guns produced is decreased, the resources previously used can be reallocated, resulting in an increase in the production of butter. However a contradiction emerges here – gun making resources do not make butter. Therefore if the quantity of gun production lowers to that of point A, the quantity of butter produced may only be at point A and the economy operates within the PPF curve, representing productive inefficiency.

The PPF can also represent the advantages of international trade. Say, for example, the economy above is more efficient at creating guns rather than butter. If it reduces the production of guns by 10, the increase in butter may only be 5. However supposing another economy is more efficient at producing butter than guns; the 10 guns could then be sold on to the other economy instead in exchange for, say, 20 units of butter. This allows an economy to operate outside the PPF, as represented by point X. From the cyber-warfare point of view, could cyber-warfare be a service that one country exports to another? (political allegiances would also most likely come into play here.)

The PPF does not always have to be a curve either. The curve represents diminishing returns, with the amount you get from reallocating resources, decreasing the more you shift from one form of production to another. Straight curves are also possible to represent a constant rate of return. PPF curves are also able to shift either to the right or left, depending on a number of different factors. For example, resources can be taken out of production and invested to increase the productive capacity of the economy in the long run. Immigration can also shift the curve to the right, representing increased labour resources. Effects of cyber-warfare however may result in the curve shifting to the left!

This marks the end of my initial readings in Economics and although so far i have only covered the most fundamental concepts in Economics, ideas about the potential use and advantages/disadvantages of cyber-warfare are already starting to emerge. Next time I shall return to Politics…

Sociological Thinkers – Part 1. no comments

Reading:

Giddens, A (2006): Sociology: 5th Edition.Cambridge: Polity.

Singer, P (2000). Marx: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: OUP.

This week my reading has covered various sociological thinkers and their particular theories. The majority of the reading was taken from Giddens (2006), as chapter four of this book covers these thinkers at an introductory level. However, I feel it is important to cover both the thinkers and the theorists in detail, and so this topic is presented in two blog posts, both published this week. This first section details key classical sociological thinkers and their differences between one another. I’ve included below a description of common areas of dispute in sociology, and the arguments or particular authors regarding these disputes.

To begin, Giddens identifies core criteria for sociological thinking:

- Thinking should be counter-intuitive.

- Thinking should make sense of a problem.

- Thinking should be able to be applied to circumstances outside the original topic or study.

- Thinking should generate new ideas.

These criteria are commonly exampled in the works of the classical sociologists, and the below arguments show that sociological theories and thinking is more difficult than some may think, as a variety of approaches to theoretical thinking exist. Here are the common controversies in sociological thinking, according to Giddens, and their advocates and enemies in sociological thinking. This blog deals primarily with the theories of Max Weber, Emile Durkheim and Karl Marx, although other theorists are discussed briefly. For basic information regarding these three classical thinkers, please see my earlier blog post.

Human Action vs Social Structure.

Thinkers from both camps argue to what extent human lives are controlled by individual action and choice, or influenced by social pressures that exist outside of individual influence.

Max Weber argues in his principle work; The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, that the development of western capitalism was unique to western culture due to the religious, frugal roots of Protestantism and Puritanism in Europe prior to the industrial revolution. The ideals of these branches of Christianity encouraged hard work and allowed for the accumulation of wealth, but disapproved of luxury and spending. Thus those who accumulated wealth were inclined to distribute their wealth through a variety of investments, wages and business purchases, which in turn fuelled the acquisition of more wealth and the eventual creation of a social class of people with a propensity to generate wealth, capitalists.

This theory is important because it is an example of how social development can be influenced by norms and ideas that may at first glance seem distant, whether historically or ideologically.

In similarity with Weber, Emile Durkheim also claims that social structure influences societal development. He perceives society as far more than the sum of its individual components, and argues that the norms and rules that society constructs for us, long before our birth and existence, will have a lifelong effect on how we live our lives, without us ever having had a say or exerted any influence on their construction. Ideas of law, religion, communication and physical interaction have been created over a prolonged societal existence, and Durkheim claims that these societal systems will continue to function independently long after we are gone.

In contrast to these theories, more contemporary thinkers, such as Anthony Giddens, have critiqued the classical arguments and provided their own arguments for human action being the fundamental drive behind societal development.

Anthony Giddens has attempted to critique the social structure arguments of the classicists with his theory of ‘structuration’. Structuration argues that while structural models occur in societies, they are only maintained by the predictable behaviour of individuals. Giddens draws parallels with language to argue that rules of use are vital in any social structure. This idea is indeed complex, and Giddens notes the paradoxical ‘duality of structure’, whereby structure and actions are seen to presume one another. For this reason, arguments regarding social structure and human action are unlikely to be resolved, sociological thinkers must simply attempt to pick a side using well informed reading and analysis.

Consensus vs Conflict.

Sociologists are divided regarding the ways in which humans live in societies. Durkheim maintains that the existence of a society, itself made up of component parts, implies a general consensus of values and norms endemic to the society on question. Therefore if one were to adopt this argument, society is consensual. Families, institutions, governments and nations are all formed out of consensual agreement by their participants and the notion that organising communally brings benefit.

This consensual argument is refuted by Marx, who argues that the inequalities which exist in societal structure foster certain interests, desires and motivations in particular groups. These interests eventually manifest as conflicts within society. According to Marx, so long as these divisions exist, there is no such thing as a stable society, as the society is constantly in flux regarding the dominant group.

Gender ambiguity vs gender specificity.

This is a concern of many of social sciences and humanities. For much of history issues of gender have been treated with an undeniably male bias, for example Durkheim presents the female gender as being of less social significance than the male because the female is more ‘organic’, that is to say, closer to nature. Thinking in this way usually leads to a situation where, if not specifically excluded from study, females are usually perceived as de facto in studies of society and the results of male thinking or male exclusive research is simply applied under this catch all notion. This type of thinking was common to classical sociologists, with a notable exception being Marx, who viewed women to be a form of ‘male property’, and therefore slaves to class divisions in ways exceeding males.

Classical views may be flawed due to the ideas and social standing of women at the time of their writing, but they do present an indication of the acknowledgement, however implicit, of females and males being independent of one another, and perhaps not subject to identical social pressures and structures. With recent progress in identifying the legitimacy of female concerns, new feminist thinking has emerged which carries with it a dilemma not dissimilar to the problem of the male centric thinking. Do females, now being equals in society, simply remain de facto members of a study, but still not uniquely identified in societal studies, meaning men and women are not judged by gender, or do studies break down societal issues into components of male and female issues, identifying a divide? This question occupies many contemporary feminist thinkers, such as Judith Butler, who argue that gender grouping may ascribe incorrect identities to social groups, for example gay men and women, when developed primarily along biological lines. The role of gender in sociology is, again, a complex one, as it explores to a large degree conceptions and ideas that are rare or even taboo in many societies.

Questions of Modern Social Development.

Debates that arise in this particular area deal primarily in Marxist and anti-Marxist viewpoints, and are concerned with the underlying factors behind the development of the modern, post-industrial revolution society (this idea is confined to Western sociological thought). Marx’s ideas regarding capitalist economics and the migration of labour may influence many sociological, political and economic theories, but other theorists argue that they do not adequately address other factors, political, cultural, environmental, which may influence societal change. In this regards, debates in this field follow a similar argument to human action vs. social structure conflicts.

Marx places high importance on economic development and capitalism, specifically the appropriation and accumulation of wealth. Capitalism is inherently expansionist, as wealth can only be appropriated when someone else has it, and so capitalist markets expand to locate and collect this wealth. In this fashion, capitalism quickly takes over all spheres of a society, as capitalists, being the dominant class, exert political and cultural pressure on the society in order to make it conform to their ideals. With this dominance comes subjugation, and the world then becomes stratified into the divisions that, one could argue, we see today. The have’s and have-nots, rich and poor, labourers and factory owners. These are products of capitalism, and social structures will continue to be shaped by the tenets of capitalism, the search for and acquisition of wealth.

Those that argue with Marx, notably Max Weber, claim that non-economic factors, such as the aforementioned construction of a religious work ethic, are just as important in shaping modern society. Weber presents the concept of ‘power’ as an important tool in reinforcing established economic and social principles, and argues that the rise of western industrial economies, and the military power which they are able to wield, has enabled a global system to emerge which reflects the economic ideals of these particular nations, and not of universal grassroots capitalism in all societies. Weber also points to the rise of scientific and technological innovation in the 19th and 20th centuries, which have fostered a form of social efficiency regarding labour, communication and interaction which he calls “rationalization”. Whether this rationalization translates as technological determinism is not clear to me at this point.

Conclusions.

This blog post has unearthed some interesting theories and ideas regarding classical sociological thinkers and their disputes with one another. We can see that sociological theories are shaped themselves by the societies, time periods and general socio-economic climate in which they were written. The disputes of the past are of course important, but should serve to remind any sociologist of the need for caution when applying past theories to contemporary issues. That is not to say that these ideas are outdated, as Giddens points out in his criteria the need for theories to be adaptable, but that adaptation should be considered by the sociologist when applying such theories to social settings which were not considered during their inception.

It is also clear that sociology has much in common with economics and politics at an ideological level, and I am keen to explore further the writings of the classical sociologists, particularly of Marx and Weber, to see where their ideas may take my own ideological development and it’s subsequent application to research.

Part two of this blog post will arrive shortly, and I will concern myself with the ideas of ‘Postmodernism’ in sociology, and present more analysis of contemporary thinkers in this field.

How to Evolve a Cellular Automaton no comments

This week, I’ve been pushing on with “Complexity: A Guided Tour”, and continued attending the Complexity lectures. Their subject matter are converging towards “in what sense do real-world distributed complex systems compute?” (e.g. ant colonies or the Web). This is very relevant to my key theme of collaborative problem solving. It builds on last week’s introduction to cellular automata. Most fascinating was an experiment that used genetic algorithms to evolve cellular automata to perform global analysis despite being highly distributed. The results was the emergence of Feynman-diagram like particles, operating at the abstracted level equivalent to the programming level of a traditional von-Neumann-style computer. Obviously, computation has been a key theme throughout, so there’s a happy overlap with the theory of computation COMP6046 lectures. I’ve enjoyed the introduction to information theory and Shannon entropy, and have chosen Comp Thinking coursework on encryption in order to build on that. The other key ingredient this week has been thermodynamics, and this has been a happy stroll back to my time in Physics. Above all the Darwin-like obvious-yet-brilliant central observation of Boltzmann that things will always tend toward the more common state – hence the mighty 2nd law of TD. So, several really engaging themes have been weaving together. Looking forward to what comes next.