Archive for October 14th, 2013

Web Doomsday: What Will Happen if The Web Just Disappeared? no comments

On an evening two weeks ago, a power-cut in Southampton plunged the city into darkness. As much of the city’s buildings lost power, people started wandering out onto the streets. Despite the power cut lasting no longer than 30 minutes, there was a faint air of panic as everyone was reminded of how much they have come to be dependent on electricity. I was one of them – living in a modern flat, no electricity means no lighting, no cooking facilities and no running water – the basic amenities of modern life.

But I was also reminded that the Web is just as vulnerable. Much like electricity, the web has become something we are dependent on. And like electricity, the complex infrastructure that delivers Internet to our homes is prone to disruption through countless ways. The Southampton power-cut was caused the failure of a single substation. Likewise, the failure of a single point on the Internet infrastructure can cause huge disruption. The reasons may be accidental or malicious.

Above: People walk the streets of New York during the 2003 blackout. It was caused by a software bug and affected 55 million people, lasting almost a day for some and over two for others.

So over the next few weeks, I am going to consider what might happen if the web were to disappear. Given that there is still over half the world’s population to start using the Web, it seems an appropriate time to why this is and whether this impacts their lives. For example, the widespread political issues surrounding web availability, such as restrictive firewalls and censorship, could provide insight into how loss of access to the Web affects us already.

Literature in Social Anthropology can tell us how humans have historically dealt with loss of perceived necessities, whether it be wartime rationing or survival during and after natural disasters. Perhaps this can help us prepare for a disaster that leads to the loss of the web. And if we did lose the Web, what would the impact be? Modern civilisation is governed through Economics, which, considering how the Web has become a platform for economic prosperity, could be one of the most affected areas.

The uptake of the web is not stopping any time soon, and the loss of the web could be detrimental to a future society. Now is an important time to get a better understanding of what the consequences of loosing the web would be.

Archaeology, crime, and the flow of information. no comments

Whether it be from property developers, civil war and conflict, treasure hunters and local enthusiasts, or just “bad archaeology”, archaeologists and heritage professionals have long struggled with the question of how to ensure the protection of sites, monuments and antiquities for future generations. Archaeological method and “preservation by record” were historically born out of situations where archaeology can not be conserved and within a desire to uphold one of the main principles of stewardship: to create a lasting archive. As archaeology is (very generally speaking) a destructive process that can not be repeated, an archive of information regarding the context and provenance of archaeological sites and finds is created to allow future generations to ask questions about past peoples.

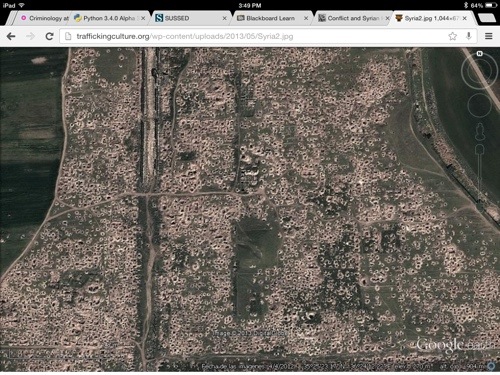

Recent years have presented numerous ethical challenges to archaeologists and and other stewards of the past, particularly where crime and illicit antiquities are concerned. Social media and web technologies in general have provided, in some cases, real-time windows into the rate of the destruction of heritage sites within areas of war and conflict. Evidence from platforms such as Google Earth, Twitter, and YouTube have all been used by world heritage stewards to plead for the protection of both archaeological sites and “moveable heritage”. Ever-evolving networks of stakeholders in the illegal antiquity trade have also been identified and linked to looted sites in areas where some have hypothesized that the sale of antiquities is actually funding an on-going arms trade in regions consumed by civil war.

Although a case could be made for investigating the nature of archaeology and crime from the angle of many different disciplines (philosophy, ethics, economics, law, psychology, to name a few), criminology and journalism were specifically chosen to offer insight into the role of the Web as a facilitator in the flow of information. Both disciplines are concerned with information flow and resource discovery – for example, in journalism the flow of information between (verifiable) sources of information through to dissemination to the public, and in cybercrime the important information exchange that drives networks of crime (both physical and virtual).

Focusing on the nature of information exchange, what would criminology and journalism contribute to the following topics?

- Social media and the dissemination of heritage destruction. What are the ethical issues surrounding the use of social media sources in documenting heritage destruction? Can/should social media sources (sometimes created for other purposes) be used as documentation to further research or conservation aims within archaeology?

- The international business of selling illicit antiquities – from looters to dealers – what role does the Web play in facilitating these networks of crime? What methods for investigating cybercrime could be applied to the illicit antiquities trade to better understand the issues surrounding provenance?

- Does the “open agenda” and the open data movement specifically (e.g. online gazetteers of archaeological sites, open grey literature reports with site locations, etc.), create a virtual treasure map and subsequently increase the likelihood of looting at archaeological sites?

Some aspects of each discipline which I believe to be relevant to the study of each (as well as the chosen topic):

Criminology and Cybercrime

- What is crime? (“The problem of where.“/”The problem of who.“)

- Policy and law

- Positivism and the origins of criminal activity.

- Digital Forensics

Journalism

- What is Journalism?

- Who are Journalists?

- Ethics and Digital Media Ethics

- Anonymity, Privacy and Source

- Bias and Conflicts of Interest

Some Potential Sources

Criminology:

Burke, R.H., 2005. An Introduction to Criminological Theory: Second Edition. Willan Publishing.

Walklate, S., 2007. Criminology: The Basics. 1st ed, The Basics. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Yar, M., 2013. Cybercrime and Society. 2nd ed., London: SAGE.

Journalism:

Ess, C., 2009. Digital Media Ethics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Frost, C., 2011. Journalism Ethics and Regulation. 3rd ed., Longman.

Harcup, T., 2009. Journalism: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed., SAGE.

Who benefits from MOOCs? no comments

My proposed title for this assignment is ‘Who benefits from MOOCs?’. These ‘Massive Online Open Courses’ have been in the ed/tech news quite a lot recently, and the University of Southampton has also got involved by joining the Open University’s collaborative Future Learn project with a number of other UK universities. Actually, the phenomenon first appeared back in 2008 at a university in a Canada, but in quite a different form to the more well-known courses promoted in some high-profile American universities.

Whatever their (fairly brief) history, these courses have aroused considerable interest in universities, the media, and investors, perhaps because of the number of potential participants (for ‘participants’ read ‘punters’?). Some courses, it seems, have indeed attracted large cohorts of students – an MIT course in electronics registered 155,000 learners last year, though far fewer (around 7,000) actually successfully completed it (Daniel, 2012).

But what can students (whether they complete or not) take away from their experience? Hopefully they learn some interesting things along the way, and possibly make some useful connections with like-minded individuals. However, for those that complete such courses, obtaining certification or formal recognition of achievement is problematic in a number of ways. It is difficult for institutions to ensure the integrity of tests results, and few universities recognise completion of MOOCs in terms of academic credit.

What’s more, designing and implementing online courses is not cheap, quick or easy (even though many optimistic departmental managers seem to imagine that a simple ‘cut and paste’ job on existing face-to-face course materials will do the trick). A key feature of MOOCs is their second ‘o’ for ‘open’ (which entails, according to most commentators, free). To provide meaningful, effective and attractive online courses is not simple (hence Les’ efforts to tap our ideas in recent FoWS lessons?) and yet universities will presumably need to justify the substantial use of resources for their construction.

So, if the completion of a MOOC has questionable value to a student facing university admissions departments or prospective employers, and universities themselves have to invest in their development, but give them away for free, who benefits from MOOCs?

I’d like to approach this question using ideas from economics and philosophy:

Economics

Although economics is often associated with the allocation of resources in business and private enterprise, public goods such as education are significant factors in the models which economists use to understand societies, economies and human activities within them. However, phenomena such as MOOCs constitute a fairly radical shift in the way education might be conducted and delivered (free to users, huge potential cohorts, geographically unconstrained, difficult to certify). This shift raises a number of questions:

- How do these new courses challenge our understanding of supply and demand in higher education?

- Knowledge is “a public good par excellence” (Gupta, 2007), but who should provide the resources to enable such massive and open access to knowledge?

- How might a ‘social cost-benefit analysis’ of MOOCs be effectively conducted in terms of a student cohort which is geographically dispersed across national boundaries?

- In what other ways might the potential economic benefits (or drawbacks) of MOOCs be analysed?

Philosophy:

From the range of sub-fields included within this discipline, I think epistemology and existentialism may provide interesting ways in which to analyse my research question. Epistemology deals with defining knowledge and attempting to understand the ways in which humans can acquire it. It might be interesting to look at the ways in which people perceive and value knowledge which is given away for ‘free’ by universities, as these institutions have previously put conditions and restrictions on student access to the knowledge which universities possess. This idea relates to an important concern in epistemology, namely the sources of knowledge.

From my brief survey of some basic literature, it seems that there is little consensus on a precise definition of existentialism. However, its fundamental concern with the individual, free will, and the individual’s responsibility for their own actions and the consequences of them may have relevance to this subject. It might be interesting to explore an existentialist view on the ways in which individuals can benefit from participation in MOOCs regardless of the (lack of) incentive of accreditation for their achievements – an existentialist might argue that it is enough to participate in such courses sincerely and with passion.

The lack of value placed on participation in or completion of a MOOC (by universities/employers/society more widely) could be seen to be in line with the existentialists’ view of the external world’s ‘indifference’ to individuals – though this does not, for them, necessarily entail any disincentive for an individual to continue striving within an indifferent world.

References

Daniel, J. (2012) Making Sense of MOOCs: Musings in a Maze of Myth, Paradox and Possibility. JIME. 18 pp. 1-20 Available from: http://www-jime.open.ac.uk/jime/issue/view/Perspective-MOOCs [Accessed 12 Oct 2013]

Gupta, D. (2007) Economics – a very short introduction. Oxford: OUP

Temple, C. (2002-2013) Existentialism. Philosophy Index. Available from: http://www.philosophy-index.com/existentialism/ [Accessed 11 Oct 2013]

Temple, C. (2002-2013) Epistemology. Philosophy Index. Available from: http://www.philosophy-index.com/philosophy/epistemology.php [Accessed 11 Oct 2013]

All in agreement? no comments

Issue: How to reach a global consensus on the balance to be struck between the right to freedom of expression and content which should be illegal on the web.

Background

Prior to the web, content classed as ‘undesirable’ (including that classed as antisocial, defamatory, obscene, pornographic, racist, malicious, threatening, abusive, or undesirable religious or political propaganda) could be regulated far more effectively.

1. Because the mediums used to distribute it were easier to control

2. Each jurisdiction could decide, make and enforce their own regulation on how the balance should be struck.

However, in the wake of the web, concerns have erupted surrounding the ease of propagation of content which could be deemed desirable in one jurisdiction and undesirable in another. The ease of accessing information originating from another jurisdiction makes it almost impossible to enforce national laws on a medium that does not recognise national boundaries.

Gaining global consensus as to the standard/ type/ level of content that should be available on the web has proven difficult. Unlike the approach to fraud or hacking, where, despite differences, a consistent philosophy and approach can be seen among jurisdictions, the balance struck between freedom of expression and illegal content varies greatly from one country to another. Certain governments are more sensitive about the expression of some political or religious views and definitions of obscene or pornographic material vary from place to place.

Therefore, how do we harmonise these different views?

Disciplines:

Mathematics

Mathematics is the science which deals with the logic of shape, quantity and arrangement. Many situations can be represented mathematically and many ‘real world problems’ can be solved using mathematical models. I will be looking to critically analyse whether it is possible to use a mathematical model to decide what content should and should not be deemed desirable on the web.

Anthropology

This is the study of humankind. It draws and builds upon knowledge from the social and biological sciences and applies that knowledge to the solution of human problems. I am particularly interested in ‘sociocultural anthropology’ which is the examination social patterns and practices across cultures, with a special interest in how people live in particular places and how they organise, govern, and create meaning. I will be looking to use anthropology to understand why different jurisdictions have different approaches to the regulation of content online and whether this knowledge can be used to understand better where the aforementioned balance should be struck.

Reading List:

Garbarino. Merwyn S. ‘Sociocultural theory in anthropology: a short history’ (1977) New York : Holt, Rinehart and Winston, c1977.

Hannerz U. ‘Anthropology’s World: Life in a twenty-first-century discipline’ (2010) London : Pluto

Haberman R. ‘Mathematical Models: mechanical vibrations, population dynamics, and traffic flow : an introduction to applied mathematics‘ (1998) Philadelphia, Pa. : Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics

Taylor, Alan D ‘Mathematics and politics : strategy, voting, power and proof’ (1995) New York : Springer-Verlag