A year in Baby SUSO

Emma Blundell and Tricia Mann (year 3) spent part of their final year as highly successful educational managers of the innovative Baby SUSO scheme. Here’s their report on how their work helped kids to participate in orchestral music:

In 2010, Southampton University Symphony Orchestra‘s (SUSO) then President, Kat Hattersley, pioneered a pilot scheme called The Baby SUSO Project which aimed to bring orchestral music to children in local primary and secondary schools. Although Southampton has an exciting and thriving music scene, there are not many opportunities for children to see a live orchestra. The Baby SUSO project aimed to cross these barriers by bringing a small part of this music scene into schools. Building on the pilot scheme’s success, Baby SUSO has now become an important student-run outreach programme, and we were elected to run the 2013-14 scheme.

In 2012-13 the Baby SUSO project visited one primary school. The repertoire for this concert featured Mendelssohn’s Wedding March from A Midsummer Night’s Dream and a medley of themes from Hans Zimmer’s Pirates of the Caribbean. The most successful piece, in terms of the children’s reactions, was the Pirates of the Caribbean medley. Film and television music is an appropriate place to introduce classical music to children because it is more likely that that they have heard it before, so for the 2013-14 Baby SUSO project we decided that the repertoire should consist of music we thought the children would immediately recognise.

The repertoire this year featured Alfred Newman’s 20th Century Fox Fanfare, Hans Zimmer’s Zoosters Breakout from Madagascar, an arrangement of Andrew Davenport’s In the Night Garden Main Theme, John Williams’ Flying Theme from E.T. and the Symphonic Suite from The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring composed by Howard Shore. We began with the budget of £1000 from the successful Learn with US application undertaken by the Music Department, which paid for scores, van hire to transport instruments, CRB checks and other costs. While last year only one school was involved, the 2013-14 project involved three, in very different areas in Southampton and with varying levels of music education currently in place. Children took part in an afternoon of student-run workshops with the musicians, which concluded with a half an hour concert. These concerts were conducted by two of the University of Southampton’s conducting students and the orchestra was made up of members of the Southampton University Symphony Orchestra, all of whom wanted to share their experience and passion for orchestral music.

Our project culminated with a playalong session where some of the children from all three schools were invited to the Turner Sims Concert Hall to play alongside SUSO. On the afternoon of 26 March, 56 children from the three schools and 52 students from the university joined together in an afternoon of music. The afternoon helped to illustrate the impact of music: I do not think there was a single person in the room not smiling by the end of the session, parents and teachers included! The children were asked to write a sentence about their trip and with these I have made a ‘wordle’ to illustrate the children’s responses. One child, aged 8, said ‘I really enjoyed the orchestra trip and I will remember it and cherish it for the rest of my life. Thank you for making this one of the best experiences of my life.’

As a part of the student-run Baby SUSO workshops we conducted a small experiment to examine the impact that just two hours of music could have on a group of children aged 8-9, in two out of the three schools visited. We asked three musicians, from three separate musical families (brass, woodwind and strings), to stand behind the groups of children and play a short scale or piece. We then asked the children to identify the instruments aurally, ie. without looking.

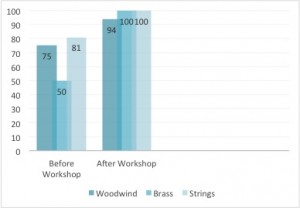

In school A, there was not such a dramatic difference between recognition before and after the workshops, but when you look at the data a larger percentage of children in school A could identify the instruments to begin with. The biggest difference was the recognition of a brass instrument, which here was a trumpet. This increased from 50% of children being able to recognise the instrument to 100%. This surprised me because we thought that the trumpet would have been an easily recognisable instrument for the children due to its frequent use within television, film and game theme tunes. The children’s ability to recognise the woodwind instrument, a flute, and the stringed instrument, a violin, did not surprise us. However, were we to do the experiment again we would be interested to take it one step further to see if the children would be able to recognise the differences within the sections, for example, between a violin and a ’cello, between a flute and an oboe or between a trumpet and a French horn.

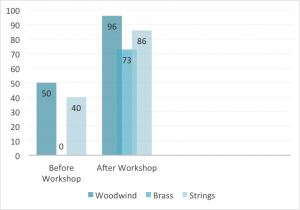

School C is in a less affluent area of the city and shows dramatically changed results after just two hours of the music workshops. Again, the brass instrument was the least recognisable at the start, with none of the children recognising the trumpet at the beginning. This increased by 73% after the workshops. The woodwind and the strings both increased by 40%.

School C is in a less affluent area of the city and shows dramatically changed results after just two hours of the music workshops. Again, the brass instrument was the least recognisable at the start, with none of the children recognising the trumpet at the beginning. This increased by 73% after the workshops. The woodwind and the strings both increased by 40%.

This experiment produced two main conclusions. Firstly, the children attending school A, situated in the more affluent area, already had a larger basis of musical knowledge, and although our workshops built on this knowledge, the difference in their learning was not as great as in school C. When conducting the workshops in school C, it became increasingly apparent that the children had less knowledge of music than in school A. Their workshop answers showed this. We feel it is important to mention that in school C there was no lack of enthusiasm to learn about the instruments. The children were all very excited to see the instruments and to learn more about them. We spoke to a few of the children during the workshops. One child commented that, “I didn’t even know the viola was an instrument, but I want to learn it!” Another was inspired by the concert and said, “I want to be in an orchestra when I grow up!” When asked what it was she wanted to play, she said she couldn’t make her mind up, but “conducting looks the most fun!”

The second conclusion we have drawn is that in school C, although the amount of music we offered the children was minimal, it has clearly had a big impact on the children’s knowledge of musical instruments. We would be interested to see how a few more similar sessions could support their enthusiasm and impact positively on their musical learning.

We feel that the 2013-14 Baby SUSO project has been hugely successful and are both immensely proud of the outcome. Since March we have been receiving emails from head teachers from other primary schools in Southampton who have heard about the project and would like to get involved. We have also been contacted directly by the Southampton Music Services, firstly congratulating us on the success of the project, and secondly asking to be involved in future projects. The addition of the Turner Sims Concert Hall ‘playalong’ session was a particular highlight for us this year. We enjoyed organising the session, arranging the music and conducting the actual session. It was, admittedly, controlled chaos at times, with over a hundred university students and primary school children playing musical instruments in a confined space, but proved truly worthwhile for all involved. One of the teachers involved commented ‘I don’t know many experienced teachers who could have had such control over that many students, especially in such an organised manner. Well done!’