Transatlantic thoughts

US scholar-performer Dr Vivian Montgomery reflects on her stay in Southampton during a Fulbright fellowship: As I near the end of my time in the UK as a Fulbright Senior Scholar, I’m astonished by both how much has happened and how much more I could do with another 6 months. I came to Southampton in January after 5 days staying in Durham Castle for the Fulbright Forum. The flooding had just started on the coast and the beach at Bournemouth, where I would live for three months with my teenage son, was a wild and windy landscape. Nearly daily, we would take the train through the New Forest (my son to school at Brockenhurst and me to Southampton), passing fields that one would think were lakes if there hadn’t been the occasional cow or horse standing helplessly around the edges.

While I had work to do, we also had adventures to pursue, and pursue we did: the New Forest, the Jurassic Coast, the Dorset countryside, Christchurch, Salisbury, the Isle of Wight, London, Bath, Poole, Winchester, Weymouth, Brownsea Island, Portsmouth. Every time I thought we had seen the oldest, the largest, the most profound, the greenest, something else would beckon on the horizon. I have hiked more miles, and through more mud, in these short months than in the previous decade. It’s been a rich and wonderful time.

The Fulbright Commission charges its scholars with being ambassadors as much as being focused on our specific projects, so every time I started to feel like my exploration and socializing was overshadowing my work, I reminded myself that it was all part of the same package. And because I consider myself as first a performer and teacher of performance practice, my work is by definition dependent upon interaction. I immediately plunged into a practice routine, working with the University’s beautiful 1790s Broadwood piano, as well as the school’s fine harpsichords. My primary performances were a solo recital in Turner Sims in March and a concert on the restored 1820s Stodart grand at the beautiful Chawton House Library in May. Both concerts revolved around variation pieces, a special interest of mine for how they lead us to consider improvisational practice, the eternal reworking of favorite melodies, and the overlap of “art” music with music of “the people.” I’ve found variation compositions and practices particularly fruitful and suggestive when investigating the musical lives of 18th & 19th century women in their homes.

My time at Chawton House, the family estate of Jane Austen, was especially gratifying because it pulled together so many elements – a legendary manor steeped in literary and women’s history, set idyllically and overflowing with staff, fellows, and visitors who, like me, are seeking out first-hand, vivifying encounters with the culture of 200 years ago. The piano itself was such an encounter, and my program, entitled “A Most Beloved Melody: British and American Piano Renderings of Favorite Songs 1790-1850,” felt particularly evocative of the musical milieu of such a setting. Here was an experience that could only be had in England, and with time available for repeated visits.

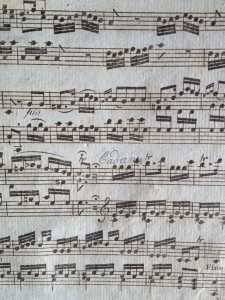

My archival research while at Southampton was of a sort I had rarely taken part in: although I rapidly discovered that the British online resources were of an order I had hardly imagined (Cecilia, British Music periodicals online, British newspapers digitized, RISM UK, the Concert Programs database, COPAC, the COPAC Women’s Library, the British Library Online, HATHI Trust, The Victorian Web), I was immediately drawn into the grittier enterprise of culling through household compilations and deciphering memoirs and wills. I spent several days examining the bound volumes in Southampton’s Special Collections, and my notes from that exploration will be tidied up and distributed to the faculty and grad students involved in connected research. I found many variation compositions that started to paint a fuller picture for me of this repertoire’s use in household musical life, and I also came across numerous compositions by women.

My most important discovery, however, was a single variation piece by an accomplished keyboardist from Leicester, Martha Greatorex. I was led on to in depth research of this artist and her works by the combination of a bold creativity, the indications of a strong improvisational practice, and her unusual history as a child prodigy, a prominent church organist, a concert impresario, and a published composer in her later years. Investigation of her context in Leicestershire, and later in Staffordshire, drew me into a deeper examination of the musical spheres of other provinces in the North and the Midlands, eventually leading me to the further discovery of another interesting pianist-composer, Maria Noke White, who also only appears to have published variations, and also after receding from public performance in the decade before her death. I’ve been captivated by these narratives, the works themselves, and the process of exposing details that would help to flesh out the musical cultures and activities around them.

My specialized interest in these two composers has brought me into extensive exchanges with several UK scholars with whom I would very likely never have crossed paths otherwise, and I’ve also been compelled to conduct sleuthing research through the historical and genealogical organizations of Leicester, Burton on Trent, Wakefield, York, and Leeds. I’ve developed some familiarity with the procedures and materials of several county records offices and parish archives, and have encountered a number of surprising resources in the process. This is a type of investigation I’ve had very little time for in recent years, and I’m certain that it’s opened up a number of new avenues, ones that will inspire me to return to the UK in the near future.

One of the elements that had originally attracted me to Southampton is the work that faculty and graduate students are doing in breathing life into the musical histories of 18th and 19th century gentry estates, with special attention to the activity of the women musicians within the households. There’s been impressive work done, under the leadership of Dr. Jeanice Brooks, on the archival, performance, and pedagogical levels, with particularly creative and comprehensive efforts directed at Tatton Park, an extraordinary National Trust site. Beyond bearing interesting scholarly fruit, the result has been the formation of something of a community, a group of researcher/musicians who share this interest and enjoy sharing their findings and ideas. Shortly after my arrival, a group convened around a guest from Birmingham who was conducting similar work on several estates, and the gathering was more fun than anyone outside of this field could imagine. It was lively, intriguing, and clearly lit a fire under a number of the participants to form a more concrete organization, and to seek funding. For my part, the fire that lit was a smaller one, to spend time at one of the manor houses whose musical enterprise hadn’t been examined in any depth. I was directed to Kingston Lacy, a National Trust site in Dorset that’s a particular treasure because of the extraordinary familial continuity the house and its contents represent. I was only able to spend one day there, but that gave me time to look through, and make notes on, the bound compilations most readily available. They tell a story of the keyboardists and singers who lived there, the instructors who were employed there, and overall interests and practices of the time, particularly between 1800 and the 1830s. Again, like at Chawton, I found that sitting in that environment while leafing through these materials was a huge part of the education I was receiving, one I could only receive while in this country.

In the last two months of my stay, we moved to the historic market town of Romsey. I traveled to give talks at the University of Wales, Leeds University, York University, the Benjamin Franklin House in London, and for the final Fulbright Forum at the University of Glasgow. I also devoted considerable time to some projects that will continue beyond my time as a Fulbrighter. These included making arrangements for my ensemble Cecilia’s Circle to record a CD of works by the 17th century Italian composer Barbara Strozzi at Chawton House in June, with such early music luminaries as soprano Catherine Bott and lutenist Elizabeth Kenny; editing several articles for submission to musicological journals; promoting my recently released CD of works by Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel and Helene Montgeroult; and writing liner notes for my upcoming Centaur Records CD release of American piano variations on popular songs. Beyond these tangibles, I’ve had the opportunity to become familiar with the work and lives of many respected colleagues, and to start to be part of a small and interesting Reform Jewish community in Hampshire.

The proximity of Southampton to London made it possible for me to make many trips there. A great amount of my time was spent in the British Library Rare Books and Music Room, where I was able to pore over original music prints, 18th and 19th century periodicals, concert programs, auction house documents, and correspondence, all associated with my areas of research. Our final two weeks in the UK were spent based in London in order to be able to more fully take advantage of everything it has to offer. Among the highlights of my activities there are gaining permission to practice on the extraordinary keyboard instruments at the National Trust’s Fenton House, visiting other important instrument collections (Horniman, Cobbe, Finchcocks), attending full Sephardic Orthodox rite Shabbat services at Bevis Marks synagogue (1726) in the East End, not to mention the many museums, historic sites, concerts, plays, markets, and a seemingly endless array of fantastic parks.

Returning to home in the US, while it’s been missed in many ways, will bring some jolts to the system, especially when it comes to train travel and other public transport, health care, and the impressive scholarship with which I’ve been surrounded. More importantly, even though we theoretically speak the same language and stem from the same cultural sources, there’s no replicating the ways of the British. As was predicted during the Fulbright orientation many months ago, I’ve crossed from standoffish and objective critique of our differences to a level of absorption that makes me sure that I return home quite changed. While I may never stop railing about the bureaucratic systems, acronyms, and overall formality of life in England, even while I’m railing, I’m now aware of, in sympathy with, the origins of these elements, and I know how much dimension, nuance, and history can be found in the cultural bedrock here. I’m so grateful to have been taught these things in my time here.