From what has already been said this afternoon we have learned what a remarkable academic career David enjoyed. What may not be as widely known is that, in addition to being a distinguished scientist and learned professor, a loving husband and the proudest of fathers, he was a founding member of the SPG, becoming recently its oldest member. The SPG is a strange and mysterious club with no rules that its members understand. Its weekly meetings are solemnly conducted in defiance of the philosopher Wittgenstein’s dictum that whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent. In the SPG meetings David contributed in the style many of us will recognise, and it was always evident that if he was not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled. It should be mentioned that what David looked for most from SPG meetings was a reasonably faithful simulacrum of that fabulous elixir Buck-u-Uppo, described by his favourite author as a marvellous specific which, when taken with some food, encouraged the elephants of Indian Rajahs to face tigers in the jungle with jaunty sang-froid. A teaspoonful of the stuff was said to be enough. Naturally, as a distinguished Cambridge-educated academic, David ignored that miserable measure.

Apparently David was keen to have the SPG involved today, as he felt that SPG involvement is likely to keep the sombre moods to a minimum. Hopefully sombre this will not be, so those of a delicate disposition may wish to avert their gaze now.

I could give you my and others’ reminiscences, but fortunately David was a superb wordsmith.

And when email was invented, it was as if it had been made for him personally; many, if not all of us will have had emails that conveyed his pearls of wisdom, or perhaps less elevated thoughts on the state of some aspect of society.

In fact, it feels pretty normal to have David quietly in the background, and today will only be unusual in that when we get home there will be no email from him, providing comment and thoughts on the proceedings.

So, I am just going to read you a tiny few of the thousands of emails from David, to try to paint a portrait of him in his own words, and help you to remember. Although I may have taken extracts, none has been edited. I think they really capture a lot of a complex and very human being.

Let’s go back to the early days. When asked about his paper with Risbeth:

Rishbeth and Barron was *the* classic paper in ionospheric studies

(though as Henry Rishbeth said to me "it did more for my career than it did for yours".)

However, it served me well when CS joined Electronics in 1986.

The old guard in Electronics had very little regard for us. But a few days after the merger, David Stewart approached me and asked in awed tones "are you the Barron of 'Rishbeth and Barron'? When I said yes, I was in!

David told Ray Steele, and Ray then accepted me as someone worthy of respect.

(He didn't change his mind about the rest of the CS staff though.)

In fact, with respect to moving to ECS:

Me, I was brought up in a hard school of academic politics in Cambridge. So when I became HoD, (Buggins' turn) I put the boot in. Within two years, we had a Faculty of Mathematics. (Derek Schofield told me later that "If a bunch of academics want something seriously enough, they will get it." As far as Maths was concerned, I was the one who wanted it seriously enough, and I got it.)

Of course, there was much satisfaction in getting the better of Graham Hills, then Dean of Science. (He accused me privately of eating hot chillies for breakfast.) But the real hidden agenda was that once we had a Faculty, it became much easier to promote the cause of CS. With evident results - as I said, Cambridge was a hard school of academic politics.

BTW, the icing on the cake is that when Mathematics was separated from Science, we got Jim Craggs installed as the Dean of Science 🙂 As I said before, Cambridge was a hard school of academic politics. The easy targets in Soton were like taking candy from a baby 🙂

Jim (Craggs)'s death reminds me of the "fight" to establish Mathematics as a Faculty in its own right. When Jim ended his term as HoD, it had been going on for ten years. Jim was the last of a line of Mathematics Professors who believed that reasoned argument would make the case. They got nowhere.

And again:

P.S Apropos not having the argument, my modest success in academic politics was in no small part due to my learning early on that you should never start something that you know you cannot possibly win. If that's the case, then you resort to 'softlee softlee catchee monkey'. If you're pretty certain you can win you go in with guns blazing. If you're a bit doubtful you wait till the sun is low, and in the enemies' eyes. Worked well for me.

I’m not sure how to introduce this one, but many will recognise it:

Subject: Measurements

Quantum Physics tells us that the act of observation can change what is being observed.

I have a medical example. When an attractive lady doctor wearing a low-cut blouse leans forward to check your pulse ... you have to look away sharpish if you don't want an elevated figure.

And of course, when it came to bureaucracy, he was scathing of the processes expected. It was a matter of pride to him that he reached retirement without ever filling in a Course Evaluation form. Nor was Political Correctness his favourite topic. When asked by the University what his Department was doing to promote women as role models, his response was swift and short: “We employ them as academics.”

Indeed, he was very proud of what he did to help women take their just place in the largely male environment of an engineering department.

The media, government and poor websites were popular targets for his criticism.

The BBC changing its schedules:

Subject: BBC

BBC have just announced that advertised programmes on BBC One are abandoned until further notice so that thay can show Andy Bloody Murray's match at Wimbledon.

Given that the audience share of digital BBC3 is so small as to be almost unmeasurable, why couldn't they can that instead?

David (hoping that Murray will do a Henman)

and

Subject: BBC

Surprise, surprise, the advertised schedule has been abandoned to allow Wimbledon coverage to over-run. And just when you think that at least the tennis is nearly over, you remember that next week it's bloody golf.

And as far as websites were concerned:

... but I'll say it again. What really, really, REALLY pisses me off is e-commerce sites that won't accept spaces in debit/credit card numbers.

Grrr!

David

And of course he woe betide those (especially students) who presumptuously called him “David”, or heaven forfend, “Dave”.

Subject: Another thing that pisses me off

Web sites that require me to register with a me as "David". I prefer Amazon's "Hello D W Barron".

David (to my friends and family)

He was also very proud of his roots. One short email during the census went:

I've been giving much thought as to what I should write in as my religion. Front-runner at the moment is 'Lancastrian'.

David was very fond of his cats. He wrote:

Breakdown of the recent food shopping trip:

Cat food: £8.28

Bird food: £6.09

Food for us: £7.80

Puts my priorities in perspective 🙂

In fact, further shopping messages included the following:

However, on the up-side the Tesco van arrived this afternoon with 12 bottles of Cru Beaujolais at 30% off list price 🙂

Among all this, we must not forget that David was a geek. Only last September he wrote:

The EDSAC 2 had two hardware modifier registers (or three if you include the instruction counter, which could be used as a modifier to achieve position-independent code – another of David Wheeler's inventions). Realising that this might be a limitation, David provided a capability to use any memory location as a modifier. The instruction '2 f n' added the contents of the address field of location 'n' to the address of the following instruction. '2' instructions could be cascaded, and could be modified with the hardware modifier registers, leading to a variety of ingenious tricks.

But David being David, he also introduced a level of indirection with the instruction '4 f n'. This modified the address of the following instruction by the address field of the location pointed to by the address in the '4' instruction. Of course, '4' instructions could be cascaded giving multiple levels of indirection: or you could use a sequence of '2' and '4' instructions each modifying the next, and possibly themselves modified by the hardware registers.

Has to be said that very few programmers used the '2' instruction, even fewer the '4' instruction, and hardly any a combination of the two. That was the ultimate accolade, akin to the top level of Unix skills "writes own troff macros". (Which I did.) Also used the '2' and '4' instructions in my EDSAC 2 programmes. I have a vague recollection that I once managed to achieve a devilish trick by cascading two '4' instructions, but at this distance in time I can't remember the details 🙁

BTW, life's unsolved mysteries: I remember the '2' and '4' instructions, but can't for the life of me remember if there was a '3' instruction in the order code 🙁

Happy days

David

And another short bit of a message:

And should I ever find myself faced with a PDP11/35 with UNIX V6 installed, I would remember that to get it up in single-user (root) mode, you count to ten after the primary bootstrap is completed, then enter '173030' on the keypad 🙂

And he did enjoy technical expertise in others:

Subject: That's ma boy!

Nik, describing his Virgin cable setup, observes that the TV Catch-up Facility is very useful, but the material is copy-protected, so you can't record it.

"Unless I put my little black box in the connection".

That's ma boy!

And David always cared deeply about the way his words looked, as well as the content. An otherwise unremarkable email had the postscript:

P.S Apologies for the mixture of Times 10pt and Courier 12pt in the text above. Eudora has a mind of its own when it comes to fonts and sizes.

But many will have in mind that David was an inspiring teacher. Of course it is hard to find emails from David about his own skills, but I have found some:

Jacky has received a well deserved promotion at King Edwards. But she's not entirely happy with her new title of 'Senior House Mistress'. As she observes, it can be mis-construed, and certainly will be by some of the lads in the Sixth Form.

But I reckon she will cope with them with elan. Runs in the blood. I remember years ago telling an unruly class that "you can try whatever you like, but I've seen it all before, so there's no point".

And another about his teaching:

(Reminds me of the time when the University's 'Teaching and Learning Committee' spent two hours deciding to call itself the 'Learning and Teaching Committee'.

What's wrong with teaching? All through Grammar School and University I had an avid desire to learn. Which was served by a long sequence of inspired teachers, to whom I am eternally grateful. I understand that my Wikipedia entry (I blame Hugh: I've never looked at it) says that I had "an almost unique lecturing style". It wasn't unique at all: it was modelled on all the wonderful teachers who had inspired me in the past. And it was based on the belief that some of the audience were keen to learn, and I had the privilege of passing on the understanding of the subject that I had achieved by the sweat of my brow. And it gave me great pleasure to do so.

And it worked. In my last year of delivering my third-year option on scripting languages, I got the graveyard slot at the end of Friday afternoon. Needless to say, I didn't get a large audience. But those who came were keen to learn. To the extent that several of them would come down to the lecture bench when I'd finished to raise a number of questions that proved they had really been listening. And we carried on an animated discussion until I felt obliged to point out that the bar had opened some time ago, and we were losing valuable drinking time.

David was always a trouper. One message ended with:

Chris Harris was equally supportive. In my final year I mucked in by giving the UCAS recruitment talks. (For most of the season my routine was to go to RSH at 09:30 for Radiotherapy, then get back to Zepler to perform at 11:00.) I have to say, modestly, that on a couple of occasions I got spontaneous applause from the audience, and I got lots of congratulatory comments from the parents who attended.

No big deal: just doing the job in a quaint

old-fashioned way.

In fact, I have a feeling that this might be a nice time to give David a round of applause.

Having had a lot of David’s more recent words, I think we can finish with some from much further back – the final words from his inaugural lecture, in 1971. Despite the bonhomie, wit and sometimes barbs we have heard, I think these words remind us of David as a scholar and gentleman, deeply concerned about the roles of Universities, both in education and creating technological advances, and who never lost his excitement at technology and its relentless march. But most of all we can hear someone who cared deeply about people:

The computer is the most far-reaching of our technological innovations, and like all technology, it can be utilised for good or ill. It is too late to turn back, and bury our processors and peripherals like Prospero’s Book, but we must avoid the danger of being swept along on a tide of innovation. If computers are to be used for good, then it is essential that everyone should understand what they are, and what they can do. Equally, those of us who are behind this technological revolution must gain a greater understanding of our tools, because out of understanding comes judgement.

We are only witnessing the beginning of the changes in Society that the wide-scale use of computers will bring. The changes are not going to be comfortable, but it is the job of those of us in the University to ensure, by education and research, that they are not catastrophic. That is why I am in the game. And, to be honest, it is great fun, too.

In the intervening 40 years it is good to report that with his help and humanity we have not lost the game. And there has been a lot of fun as well.

“Hugh Glaser (with help from the SPG).”

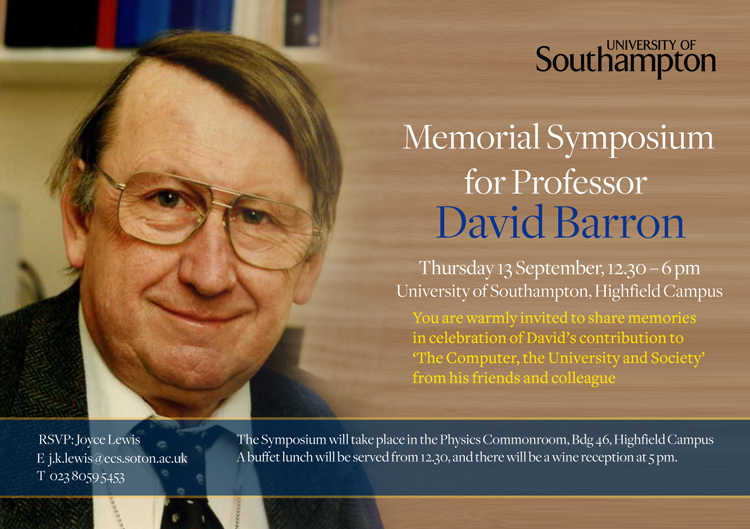

Memorial Symposium for Professor David Barron

Memorial Symposium for Professor David Barron